There are several reasons an individual can have differing views from a scientific consensus. They may lack knowledge of the subject, the “deficit model,” in which case, greater education is all that is necessary. While a popular approach, it has shown little efficacy. This failure led to the consideration that “people’s beliefs are shaped more by their cultural values or affiliations,” selectively cherry-picking information to conform to their worldview. The great success of managing hypertension in the black community through barbershops supports that view. The Dunning-Kruger effect, often wrong, never in doubt, adds a new wrinkle to the possibilities – that the most vehemently anti-consensus are also the least knowledgeable but the most confident in their views.

The researchers writing in Science Advances considered seven issues where we currently have a published scientific consensus:

- The safety of GMO foods

- The validity of anthropogenic climate change

- The benefits of vaccination outweigh its risks

- The validity of evolution in explaining human origins

- The validity of the Big Bang theory in explaining the origin of the universe

- The lack of efficacy of homeopathic medicines

- The importance of nuclear power as an energy source

They surveyed 3200 online participants, asking 34 true-false questions to calibrate the individual’s “objective” knowledge. Additionally, they asked a series of questions to quantify the individual's confidence in that information, their “subjective” knowledge, the “never in doubt” part of my family motto.

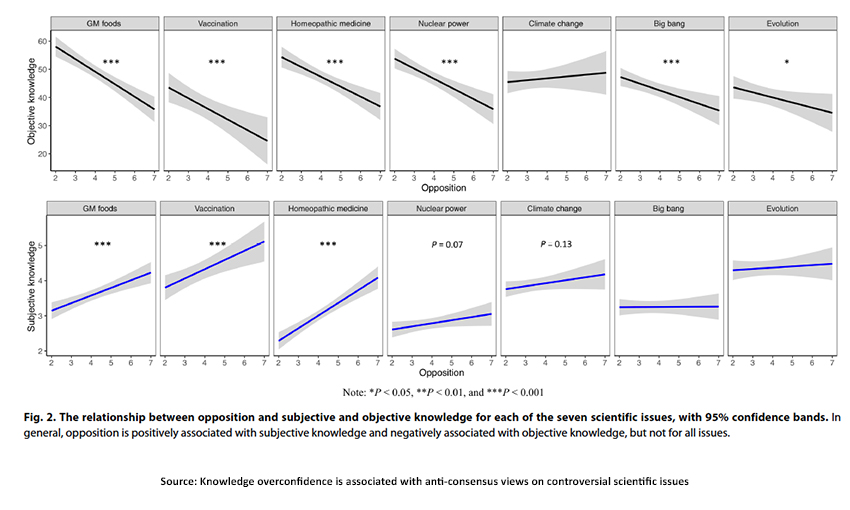

For these seven topics, the researcher’s found the Dunning-Kruger effect among those most vehemently opposed to the scientific consensus. Their objective knowledge of the topic was inversely proportional to how firmly they held those convictions. Here is the breakdown by topic.

While it is true that "often wrong, never in doubt" was in effect in all of the scenarios, there were a few exceptions, notably the Big Bang and evolution, as explanations of our origins seemed to show a bit less confidence in their understanding.

Climate change also differed from the other consensus issues. The researchers felt that political polarization impacted this topic and mitigated the Dunning-Kruger effect. The researchers conducted additional studies directed at COVID vaccination and mitigation behaviors. Lower willingness to be vaccinated or follow mitigation behaviors was again associated with insufficient objective knowledge and greater subjective confidence in those beliefs. Interestingly, about 28% of the participants rated their knowledge of mitigation strategies as more significant than that of scientists. Unlike other studies, the researchers did not claim that political affiliation was the critical driver for COVID behavior.

There are a few key points to consider. Some of these consensus issues, specifically nuclear power and, to a lesser degree, childhood vaccination, are trade-off issues, benefits vs. harms. Confidence in misinformation may not play as significant a role. Among scientists, the consensus around nuclear power stands at around 65%; the consensus around GMO foods' safety is 98%. From a policy point of view, more education will not convince those opposing the scientific consensus. What may, in fact, alter their opinions are the behavior of others. The next article will find who those others are and their impact.

Source: Knowledge overconfidence is associated with anti-consensus views on controversial scientific issues Science Advances DOI: 0.1126/sciadv.abo0038