First, you can find the entire report of the Aesthetic society here. My initial foray into learning about gender-affirming surgery can be found here.

This study looked at the out-of-pocket costs for gender-altering surgery; for those that read my previous article, “bottom surgery.” The dataset of 771 patients from 2007 to 2019 comes from employer-sponsored health insurance, so we have no information on those Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries. Commercial insurance covers about two-thirds of our population, roughly 230 million. But a careful read tells us more than just some price information.

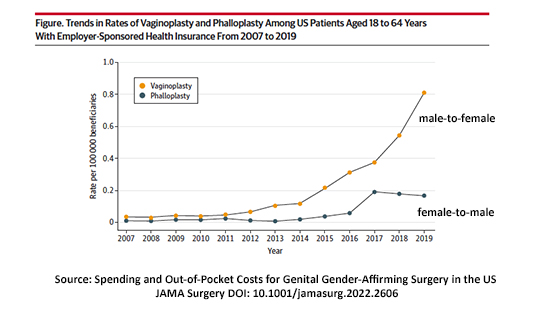

The outcomes of interest were the costs, both out-of-pocket and insurance covered for two procedures, vaginoplasty (male to female transition) and phalloplasty (female to male transition). All the prices are in 2019 US dollars, so these are underestimates given our current inflation rates.

While the number of procedures has increased over time, the increase in vaginoplasty for male-to-female transitions has been more significant. In 2019 essentially 1 in 100,000, 0.001%, underwent one of these two procedures. Population-wise, by extrapolation, we are speaking about 350,000 US transgender individuals with commercial insurance.

While the number of procedures has increased over time, the increase in vaginoplasty for male-to-female transitions has been more significant. In 2019 essentially 1 in 100,000, 0.001%, underwent one of these two procedures. Population-wise, by extrapolation, we are speaking about 350,000 US transgender individuals with commercial insurance.

Gender-affirming surgery is offered in 26 states, in 71 practice locations, involving 377 surgeons. Based on a reported 1,100 gender-affirming procedures in 2019, this averages 15 cases per practice or a little over 3 cases a day nationally – despite the media coverage, this remains an infrequent procedure. Because of this skewed distribution, roughly 60% of patients were treated out-of-state – a form of internal medical tourism.

- For vaginoplasties, a complex procedure, out-of-pocket medical costs were $2953 [1], and total charges were $59,673. These costs were higher for those receiving care out-of-state.

- For phalloplasties, a still more complex procedure, out-of-pocket costs were $2120, and total expenses were $148,540. Again, prices were higher for those receiving out-of-state care.

- In both instances, out-of-state care was provided for more people from our Southern states than the other regions; their costs were the highest. In comparison, most patients in Western states had in-state care and lower costs.

- The bottom line, out-of-state care increased out-of-pocket costs by 49% and total costs by 9%. Overall, the cost of surgical care has risen 43% since 2015. In comparison, the cost of living during this period rose about 20%.

- Despite increased commercial insurance coverage, much of this care remains self-pay. In one study of 40 Fortune 500 companies, 25% of plans excluded these procedures from coverage.

Let’s apply a different lens.

Those bullet points summarize the researcher’s findings, but other insights emerge if we look at the study differently. 50% or more of these procedures were performed out of state, as I said briefly, a form of “internal” medical tourism. Medical tourism is often thought of as global; dental work in Mexico or a lower-cost aesthetic procedure while on vacation in Asia. But the weakness of medical tourism, where to turn when procedures go awry, is equally true for out-of-state gender-affirming surgery as the dental work in Mexico.

Medical tourism is prompted mainly by the paucity or maldistribution of surgeons specializing in this care in that region, although surgical experience and techniques offered will always play a role.

Complications from vaginoplasty include a 1% rate of fistulas, 11% vaginal narrowing or strictures, 4% tissue death, and 3% prolapse (eversion of the tissue outside the body). For phalloplasty, stricture of the urethra (the tube passing urine from the bladder) can be as high as 33%, and tissue death in the range of 8%. If a surgeon were to travel from town to town doing these " itinerant " procedures, they would deliver poor and unethical care. The care is flawed because the follow-up care in terms of accessibility and expertise is inadequate. That it is the patient, not the physician, who travels, may mitigate some ethical concerns, but it does not change the poor quality of care received.

Why title the article body-affirming surgery? First, gender-affirming surgery is a subset of the more general body-affirming term, but it engenders a host of emotions making the discussion more impassioned and difficult. Second, we feel much differently when we discuss other body-affirming procedures. Many aesthetic procedures I mentioned previously, like liposuction, breast augmentation, and reduction, are heavily advertised and sought. We become indignant if our health insurance doesn’t cover these elective “necessities.”

Or consider this “edge case,” bariatric surgery for weight loss. Bariatric surgery is often touted as the best option for those with “morbid obesity,” a degree of excess weight that adversely impacts their health. But, according to at least one study, the most common reason for care is health impacts, at 28%; appearance is the next most common reason, at 24%. Ah, you say, gender-affirming surgery is treating no underlying medical condition; this is just a new-age woke idea. But in a study of 27,000 transgender individuals, this type of surgery was associated with a 42% decrease in psychological distress and a 44% decrease in suicidal ideation.

Two problems of living with your body, one involving weight, the other gender. Why is one so emotionally charged and controversial when both treat dysphoria and yield measurable benefits? Feel free to discuss among yourselves why that might be.

[1] This did not include travel and housing expenses.

Source: Spending and Out-of-Pocket Costs for Genital Gender-Affirming Surgery in the US JAMA Surgery DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.2606