"Clean cooking is commonly defined as cooking with fuels and stove combinations that meet the standards set by the World Health Organization’s Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality.”

I’ve been writing about the drumbeat to end cooking with gas because of its contribution to indoor pollution (here, here, and here) when this “clean cooking” study was published. The WHO guidelines, written in 2014, set standards for PM2.5 , particulate matter and CO, carbon monoxide. Fun fact - NO2, the concern of researchers here in the US, is not mentioned. The researchers in this study of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) created a model combining geospatial data, socio-economic information, and technical specifications for various stoves and fuels.

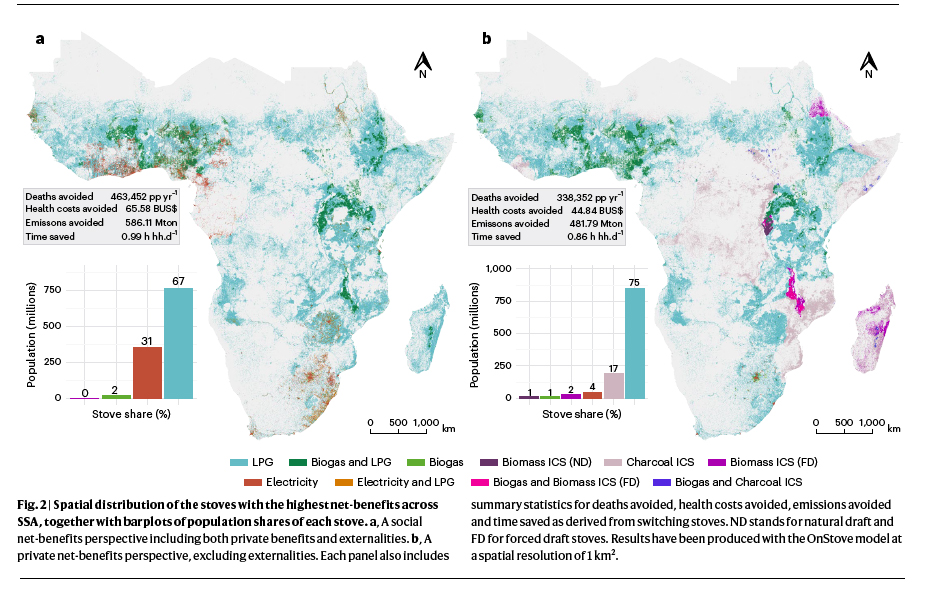

Their model, OnStove, considered several benefits, reduced morbidity and mortality, emissions, and time saved, along with the costs for obtaining these stoves, fuel, and maintenance. In a world where one size does not fit all, the geospatial data allow them to optimize the stove choices to the availability of resources. Here is the map of their findings.

Electricity was the cleanest solution for indoor pollution, followed by natural gas. The predominant cooking fuels in SSA are biomass, wood, and dung, so it is easy to see why electricity and gas were so much better. But despite electricity’s pollution advantage, gas was the optimal choice 67% to 75% of the time, two to five-fold more frequently the fuel of choice.

Electricity was the cleanest solution for indoor pollution, followed by natural gas. The predominant cooking fuels in SSA are biomass, wood, and dung, so it is easy to see why electricity and gas were so much better. But despite electricity’s pollution advantage, gas was the optimal choice 67% to 75% of the time, two to five-fold more frequently the fuel of choice.

The map visualizes the tradeoffs to households - the cost of the stove and fuel, savings on health care, and the time saved no longer gathering fuel. The map on the left expands the tradeoffs to consider population benefits or costs, like greenhouse gas emissions and the infrastructure needed to bring the fuels to the homes. As always with models, uncertainties over specific values “may influence the results.” The fact that the current cooking fuels are not ideal under any circumstances and that 83% of the population is using these non-ideal fuels,

“…indicates the extreme disconnect between the stove options that are ideal for social well-being and those that people are actually using."

What might cause this disconnect?

- “…time savings and health benefits may not always be salient to households and particularly among household decision-makers. …typically male heads of households …[who rarely] bear the majority of the burdens of fuel collection and exposure to pollution from combustion in the kitchen environment.”

- Underdeveloped supply chains – an infrastructure to supply gas or electricity

- Liquidity constraints – an economic term saying households do not have the money for the stoves and increased fuel costs

- “Cultural and peer influences whereby people mimic the costly behaviours of others around them.”

- “A lack of salience for non-pecuniary benefits” is another way of saying that we discount the consequences of our healthcare choices when those consequences are in the future and not now. Tobacco smokers lack that salience.

Costs – “all costs (and benefits) are relative to the current stove situation.”

Little research involving switching US cooking from gas to electricity looks at costs, especially for our infrastructure. In SSA, with little consistent infrastructure, universal residential electrification would cost an estimated $41 billion. Upgrading the existing infrastructure, be it gas or electric, would cost roughly 25% of that. While the situation in the US is dramatically different than SSA, transitioning to electric homes will stress our existing power grid, a grid that can be surprisingly brittle, as the citizens of Texas have discovered. The cost of running all the electric cars we are urged to purchase will require additional capacity. Do you believe the vagaries of the sun and wind will fill the gap? Even the most ardent supporters of alternative energy recognize that we need a more consistent source, and for the moment, that comes down to gas and, dare I say, nuclear.

The authors note that there are three ways to achieve the social optimum in the face of what they characterize as a market failure.

- Subsidies to reduce the cost to households to switch to cleaner cooking

- Taxes on those who pollute

- “Command-and-control regulations that limit choices.”

In SSA, traditional stoves and fuel are inexpensive if they are bought at all, so subsidies seem the best solution. But in the high-income world, we already see command and control regulations concerning new housing. The pilot studies of converting from gas to electric were all involved subsidizing participants to provide new stoves, cookware and the cost of bringing in electricity. At the cost of, say, $10,000 per apartment, the cost of retrofitting 162,143 NewYork City Housing Authority (NYCHA) apartments is over $1 billion. With those costs and the need to be socially just and not leave these individuals to suffer the indoor pollutants of gas cooking, can taxes on gas be far behind?

Source: A geospatial approach to understanding clean cooking challenges in sub-Saharan Africa Nature Sustainability DOI: 10.1038/s41893-022-01039-8