Let’s begin with the basics. In addition to written examinations, all practicing physicians in the US must complete at least one year of on-the-job training (OJT), formerly called an internship. For those pursuing more specialized practices, including family practice, there are 2 to 5 or more years of OJT labeled as residency or fellowship. The gateway to this is the national match that tries to give graduates and training programs their first choices – a process that can never be 100% successful. [1]

This year 48,156 applicants were competing for 40,375 positions. You needn’t have an advanced degree in mathematics to see that there were winners and losers. Among the statistics:

- US graduates from medical (MD) or osteopathic (DO) programs matched 94-92%, respectively, with one of their choices.

- Graduates training outside the US did somewhat worse; 68% of US graduates of foreign schools matched, and 60% for non-US graduates of those schools.

- Orthopedics, plastic surgery, diagnostic radiology, and thoracic surgery filled all of their slots

- Emergency Medicine and Family Practice, not so much.

As you might anticipate, self-congratulations quickly appear on social media by the students successfully matching, their medical schools and some specialty societies. There were also, as to be expected, some niggling arguments over the numbers. As Bryan Carmody MD [2] writes,

“..there were still a lot of applicants who went home empty-handed on Match Day: 8,130 applicants who submitted a rank order list did not match to any PGY-1 position. Another 3,049 never submitted a rank order list (likely because they received no interview offers).”

When using those numbers, the percentage of matched applicants drops to 80%. And one has to ask why 3,049 medical school graduates were not even interviewed; what does that say about the support system of their schools? Dr. Camody also points to another bit of Mathmagic.

“In reality, most medical schools conflate their match rate (the proportion of students who are assigned a residency position in the Match) with their placement rate (which includes students who went unmatched but managed to get an unfilled position after the Match was over).

From the schools’ standpoint, this distinction may not matter – their students got a residency position, right? But for a student who missed the chance to train in their dream specialty and instead had to settle for a one-year preliminary position and the uncertainty of trying to match again in a year, it’s a big deal.”

The wringing of hands

Family practice, the heart and soul of primary care, tried to put their best face on the match results; after all, there is a physician shortage. There were an additional 571 residency positions available this year. According to the National Residency Match Program (NRMP), 94% of positions filled, a rate that has remained constant over the past few years. That said, family practice is not attracting as many US graduates as other specialties. US MD or DO graduates filled about a little more than half of those slots; the remaining spaces were filled by graduates of foreign schools.

Gnashing of teeth accompanied the hand wringing when discussing Emergency Medicine training, which failed to fill 18% (554 of their 3,000+) slots. This follows a smaller failure to fill last year.

“Most observers considered last year's number, which was also unprecedented at the time, part of a pandemic hangover.

They were wrong.” - Why Are Emergency Medicine Residents Disappearing?

While burnout, increased workloads, diminished autonomy in the face of employment by large venture capital-based companies, and the rise of mid-level providers are mentioned, the author of that second opinion offers an economic basis for the dwindling interest. He suggests that a decline in physician reimbursement by government and private payers has led to increasing deployment of less expensive mid-level nurse practitioners and physician assistants “supervised” by physicians but costing far, far less. And he does add an interesting wrinkle. Emergency Medicine residents, earning a starting salary of $60,000, can also supervise those mid-level providers, meaning you need fewer Emergency Medicine physicians that have completed training. Another disincentive to hiring a fully trained doc, in many instances, hospitals are paid significant amounts for those Emergency Medicine residents by the government, making them, dare I say, on par with student-athletes in terms of value to an institution.

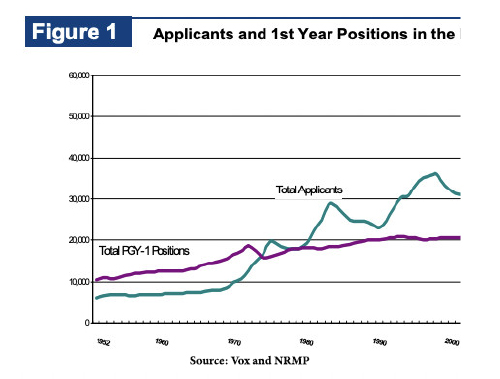

Vox suggests that the mismatch is primarily due to regulating the number of medical school graduates and residency training slots. In the 1980s, we feared a surplus of physicians, and a cap was placed on medical school enrollment – we graduate about 27,000 new doctors a year, which is rising. Physician dissatisfaction, which began before the pandemic, has hastened the exit of many older physicians, so now we are faced with an inadequate supply. They point to a second bottleneck in the road, the shortage of residency slots. Many of these residency positions are funded by Medicare. That funding has long favored hospitals and health systems with high costs [2] and large volumes of Medicare beneficiaries, i.e., urban hospitals. Additionally, Medicare has placed caps on how many residencies are funded. This is a red meat issue for those concerned with over-regulation of the free market and those who believe the invisible hand needs some help.

Vox suggests that the mismatch is primarily due to regulating the number of medical school graduates and residency training slots. In the 1980s, we feared a surplus of physicians, and a cap was placed on medical school enrollment – we graduate about 27,000 new doctors a year, which is rising. Physician dissatisfaction, which began before the pandemic, has hastened the exit of many older physicians, so now we are faced with an inadequate supply. They point to a second bottleneck in the road, the shortage of residency slots. Many of these residency positions are funded by Medicare. That funding has long favored hospitals and health systems with high costs [2] and large volumes of Medicare beneficiaries, i.e., urban hospitals. Additionally, Medicare has placed caps on how many residencies are funded. This is a red meat issue for those concerned with over-regulation of the free market and those who believe the invisible hand needs some help.

Both sides of that argument overlook another rate-limiting factor, patients and teachers. All of this after-graduation training is on the job; we learn by doing and doing a lot. You can add residents to a training program, but if you don’t increase the patient base, you dilute their experience. Academics and the wannabes (those in private practice that also “train” residents in exchange for an academic “associate” title) are not all interested in teaching. That requires an additional skill set beyond doing; it requires you to adopt a “beginner’s” mind and accept that it will require more time on your part. As Dr. Samuel Shem wrote of medical students, and equally applicable to residents, in the House of God,

“Show me the medical student that only triples my work, and I will kiss their feet.”

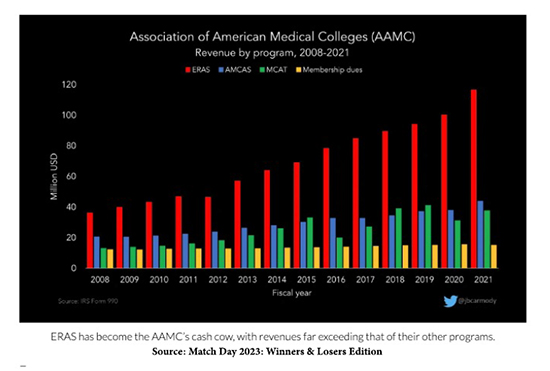

As Dr. Carmody shows in this graph, there is a winner every year in the match. That would be the Association of American Medical Colleges that runs the NRMP (in red), along with the medical school application process (in purple) and the Medical College Admission Test (in green).

As Dr. Carmody shows in this graph, there is a winner every year in the match. That would be the Association of American Medical Colleges that runs the NRMP (in red), along with the medical school application process (in purple) and the Medical College Admission Test (in green).

I find it heartbreaking that after four years of post-graduate training, the schools that so willingly took our tuition are not more deeply involved in helping its graduates find a place to practice all the wonderful knowledge they have been given.

[1] Graduating students submit a ranked list of programs they wish to join; residencies submit a ranked list of students they will take. Students are matched to the highest residency they can obtain.

[2] Hospitals receive a percentage of their spending, so with a bit of magical spending, employing resident physicians becomes a revenue rather than a cost center.

Sources: Medscape, After the Match: Next Steps for New Residents, Unmatched

Healio, News Record number of primary care positions offered in 2023 Match Day

NRMP, NRMP® Celebrates Match Day by Publishing the Results of a Record-Breaking 2023 Main Residency Match®

MedPageToday, Why Are Emergency Medicine Residents Disappearing?

MedpageToday The Unmatched Need Not Suffer Alone

Vox, Why well-qualified medical school graduates can’t get jobs — despite doctor shortages

Match Day 2023: Winners & Losers Edition Bryan Carmody, The Sheriff of Sodium