“being in poverty is bad for one’s health.”

That is a hard statement to argue with, and a great deal of data supports that general contention – with one limitation. Poverty is the stand-in, the social and cultural “biomarker” for difficulties accessing care, providing nutritious and healthful meals and living environment, meaningful or at least a sustainable income from work, and an absence of stressors like crime and violence – all the social determinants of health.

The current study sought to “quantify” the association between poverty and mortality. To understand their findings, we must begin by understanding their innovative, “higher quality” measure of household income. To do that, we turn to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Calculating poverty

The census bureau measures poverty by calculating a family's pre-tax income, which includes various cash payments and monies derived from investments. [1] Of course, in almost all cases, those in poverty have no investments to consider, nor do they have capital gains or losses. This information is compared to 48 possible poverty thresholds based on the size and age of family members without consideration for their geographic location. By the Census Bureau's definition, those below the threshold are in poverty. The official poverty rate was 11.6% in 2021.

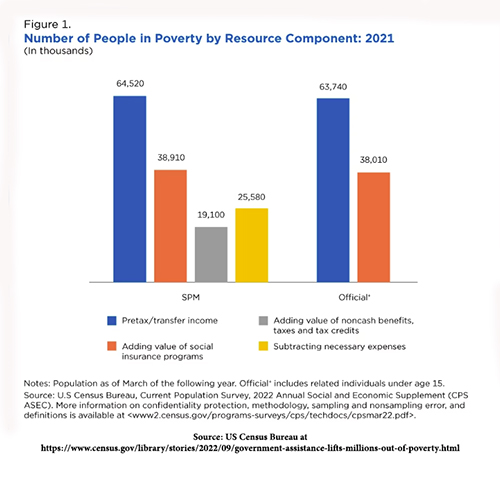

Many “low-income” individuals and families also receive tax credits and noncash benefits like SNAP (food  stamps), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or housing subsidies. These are not counted in the poverty rate but are measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which in 2021 was 7.8% – demonstrating “taxes and noncash government programs can help lift more people out of poverty.” You can see the effect of different definitions of poverty from this graph. [2]

stamps), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or housing subsidies. These are not counted in the poverty rate but are measured by the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which in 2021 was 7.8% – demonstrating “taxes and noncash government programs can help lift more people out of poverty.” You can see the effect of different definitions of poverty from this graph. [2]

The valuation of poverty used in this study is more reflective of the grey bar, the lowest estimate of people in poverty. Their threshold was 50% of the median income in each locale. As the authors were economists, I must add one more complexity; poverty is not a steady state condition. Many of us “escape” the poverty of our first job, becoming more wealthy in our middle years, only to return to poverty in our final days. Economists make a distinction between current and persistent or cumulative poverty.

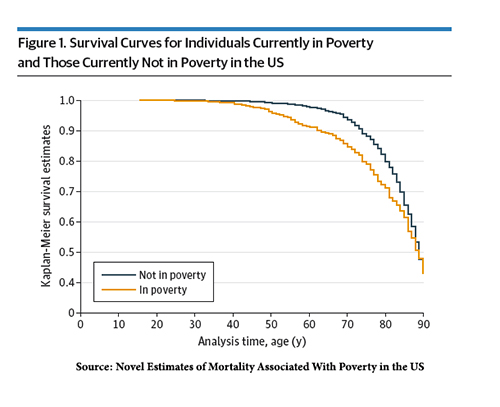

Current poverty is associated with a greater mortality hazard of 1.42 [3]

Current poverty is associated with a greater mortality hazard of 1.42 [3]- Cumulative poverty is associated with a greater mortality hazard of 1.71

- For those over age 15, 6.5% of deaths were attributed to current poverty, 10.5 to cumulative poverty.

The graph demonstrates the survival curves, which separate in the 40s and come together at age 65.

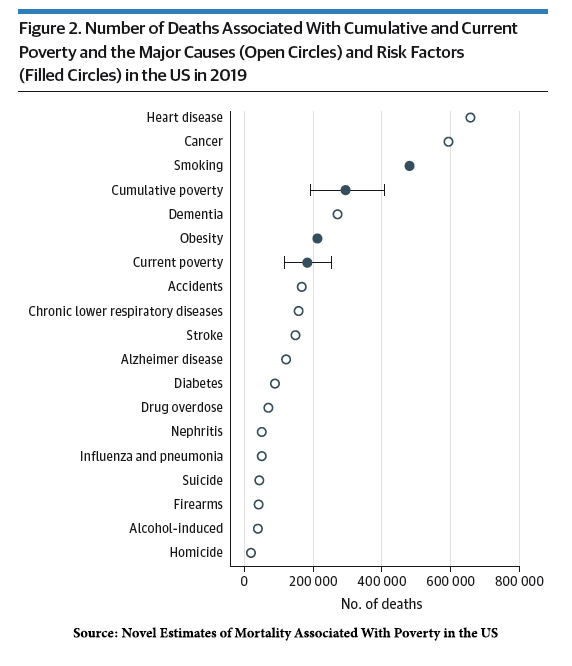

To make their final point, the researchers also show how these poverty-attributable deaths compare to other risk factors.

Only smoking, cancer, and heart disease take more lives leading to the following statement.

Only smoking, cancer, and heart disease take more lives leading to the following statement.

“We propose that poverty should be considered a major risk factor for death in the US.”

While it is undoubtedly true that poverty exacerbates all of those causes of death and risk factors, it is far more challenging to separate poverty as an isolated factor. For example, smoking is more common among those with lower income and education, as is poverty. This is when the population attributable factor, the fraction of those smoking with and without poverty, would be useful.

The is another odd quality about this paper. A movement is underway to remove race as a social construct from medicine. Before you rush to your side of the aisle, this means that phenotype categorization is a poor biological standard: "… there is no gene or cluster of genes common to all blacks or all whites.” A closer examination shows any number of biological differences within these categorical phenotypes. But isn’t poverty a social construct? If you followed the varying calculations of poverty by the Census Bureau, you would have to conclude it is a category without a biological underpinning – it may or may not help reduce disease. Still, I believe it is a rhetorical stretch to consider it a risk factor that health care can solve.

###

[1] Included are earnings, Unemployment compensation, Workers' compensation, Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, Public assistance, Veterans' payments, Survivor benefits, Pension or retirement income, Interest, Dividends, Rents, Royalties, Income from estates, Trusts, Educational assistance, Alimony, Child support, Assistance from outside the household, and other miscellaneous sources

[2] The Supplemental Poverty Measure also measures family size more broadly. Basically, anyone living in the household and the poverty threshold is not three times the cost of “a minimum food diet in 1963” but expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, utilities, telephone, and internet. They also adjust for geographic location. The same income in a rural area may not be considered impoverished compared to an urban area, like New York or San Francisco.

[3] Hazard, in this instance, describes the probability of dying among the impoverished relative to the non-impoverish at a given moment. For cumulative poverty, the time frame is 10 years.

Source: Novel Estimates of Mortality Associated With Poverty in the US JAMA Internal Medicine DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0276