The Alpha-Gal Primer

“Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS) is an emerging, tick bite–associated allergic condition characterized by a potentially life-threatening immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated hypersensitivity to galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), an oligosaccharide found in most nonprimate mammalian meat and products derived from these mammals.”

Translation – AGS is an allergic condition to a sugar (oligosaccharide) found in meat and other dairy products.

Alpha-gal is not a new concern; its presence in pigs and our sensitivity has long been a concern in xenotransplantation – the transplantation of pig organs to humans. It is spread by the bite of the Lone Star Tick, whose saliva contains alpha-gal.

In some individuals, an immune response mediated by IgE occurs. This response is an immunologic puzzle because our immune system is relatively tolerant of polysaccharides like alpha-gal, and an allergic response without the involvement of our T-cells is uncommon. It is atypical for a food allergy which most often begins in childhood and is frequently associated with underlying sensitivity that we would associate with asthma or hayfever (atopic sensitivity). Many of those affected have been eating meat and dairy products for decades.

Another oddity about alpha-gal is that the onset of symptoms is, in most, but not all cases, delayed by several hours, making an association between the symptoms and its cause difficult. Those symptoms include ones impacting our GI tract (nausea, vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea), respiratory tract (runny nose or shortness of breath), and skin “rashes.” It can also result in fatal anaphylactic reactions, but it usually presents as a skin rash.

The delayed timing of those symptoms compared to the usual allergic reactions to food occurs due to the absorption of alpha-gal bound not to proteins but to fat, specifically triglycerides, that occurs 4-5 hours after a meal. More severe reactions to alpha-gal are experienced if the meal involves alcohol or if you exercise shortly after eating; alcohol and post-prandial exercise are associated with increased fat circulating in your blood.

The diagnosis of AGS is difficult because the usual pinprick test with allergies can frequently be falsely negative, invoking little in the way of a response. The gold standard, a food challenge may result in a fatal anaphylactic reaction, so it is rarely considered. The most reliable test currently is a search for alpha-gal-specific IgE antibodies. Problematically only 5% of individuals with alpha-gal IgE antibodies have AGS.

The CDC Study

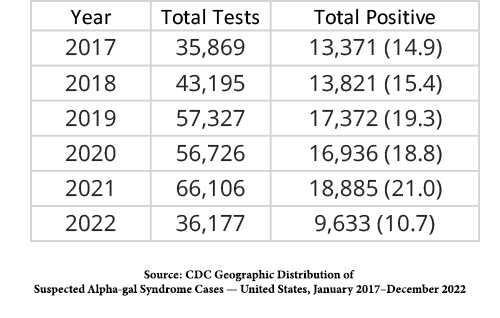

The study looked at 295,400 individuals undergoing testing for alpha-gal IgE antibodies over a 5-year interval.

90,018 (30.5%) persons received a positive test result and were classified as having suspected AGS.

There were an increasing number of individuals tested. The media reported a 41% increase over four years, but of course, the study was for five years. It is uncertain whether less testing and a lower percentage of positivity make 2022 an anomaly.

There were an increasing number of individuals tested. The media reported a 41% increase over four years, but of course, the study was for five years. It is uncertain whether less testing and a lower percentage of positivity make 2022 an anomaly.

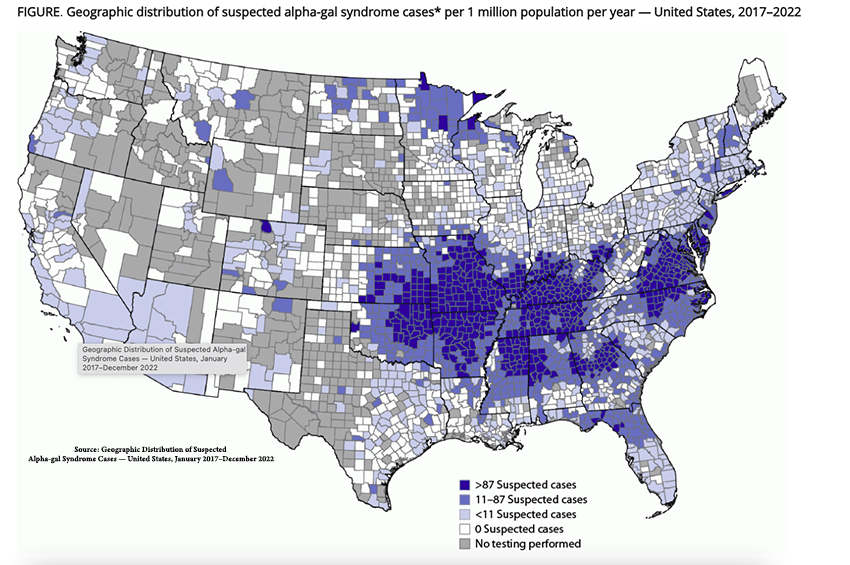

“Persons with suspected AGS were predominantly located in areas where the Lone Star Tick is known to be established or reported, particularly throughout Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Suffolk County, New York.” As you can see from the map, the risk is not evenly distributed.

The sharp-eyed reader will note the relative lack of cases in the Lone Star State, Texas – the Lone Star tick gets its name from the marking on its back, not its origin.

Physician Knowledge

The data collected by the CDC from a panel of 1,500 (1,000 primary care physicians, 250 pediatricians, and 250 PAs and NPs) responding to a questionnaire on AGS

- 42% of respondents had not heard of AGS

- Of the 58% aware of the condition, 78% had not diagnosed AGS in the previous year; and 6% had diagnosed or managed more than five patients. 48% reported they did not know the correct diagnostic test to order. The bad news, provider “knowledge” was inversely related to the number of cases identified – the less we know, the more we “diagnosed.” The good news – 66% of respondents “indicated that guidelines for the diagnosis and management of AGS, respectively, would be helpful clinical resources.”

- Pediatricians, the physicians most likely to encounter food allergies among their patients, were the most knowledgeable. And despite our poor diagnostic skills, 58% of those healthcare providers were able to provide appropriate counseling - “tick bite prevention, eliminating red meat from their diet, exercising caution when receiving new medications and vaccines, and recognizing and managing anaphylaxis.”

For context, the CDC reports that food allergies are prevalent among US adults at 6200/100,000. For AGS syndrome, that number is 18.8/100,000. By the numbers, even with underreporting, AGS is an orphan disease.

Source: Geographic Distribution of Suspected Alpha-gal Syndrome Cases — United States, January 2017–December 2022 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)

The α-Gal Syndrome and Potential Mechanisms Frontiers in Allergy DOI: 10.3389/falgy.2021.783279

Health Care Provider Knowledge Regarding Alpha-gal Syndrome — United States, March–May 2022 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)