Oxycodone, heroin, fentanyl, xylazine. And now we have nitazines, for example, isotonitazine, which is about ten times more potent than fentanyl and increasingly showing up in street drugs.

The order in which I placed these drugs is not accidental; they are progressively more deadly. It's an example of the "iron law of prohibition," which Cato Institute's Dr. Jeffrey Singer, also an ACSH Scientific Advisory board member, has been writing about for some time. In particular, Dr. Singer authored a piece titled "Nitazene Overdose Deaths on the Rise—The Iron Law of Prohibition Cannot Be Repealed" – the harder the enforcement, the harder the drug.

As a chemist, I was intrigued by a paragraph in a recent JAMA Network Open article:

The exact motivation to produce nitazenes and brorphine (1) are unclear. The increased regulation of fentanyl and fentanyl analogues throughout the last decade may have led to a change in the chemical precursors required for clandestine laboratory production that were not yet regulated. This change in chemical precursors may have led to these newer and more potent opioids. [emphasis mine]

Source: JAMA Network Open

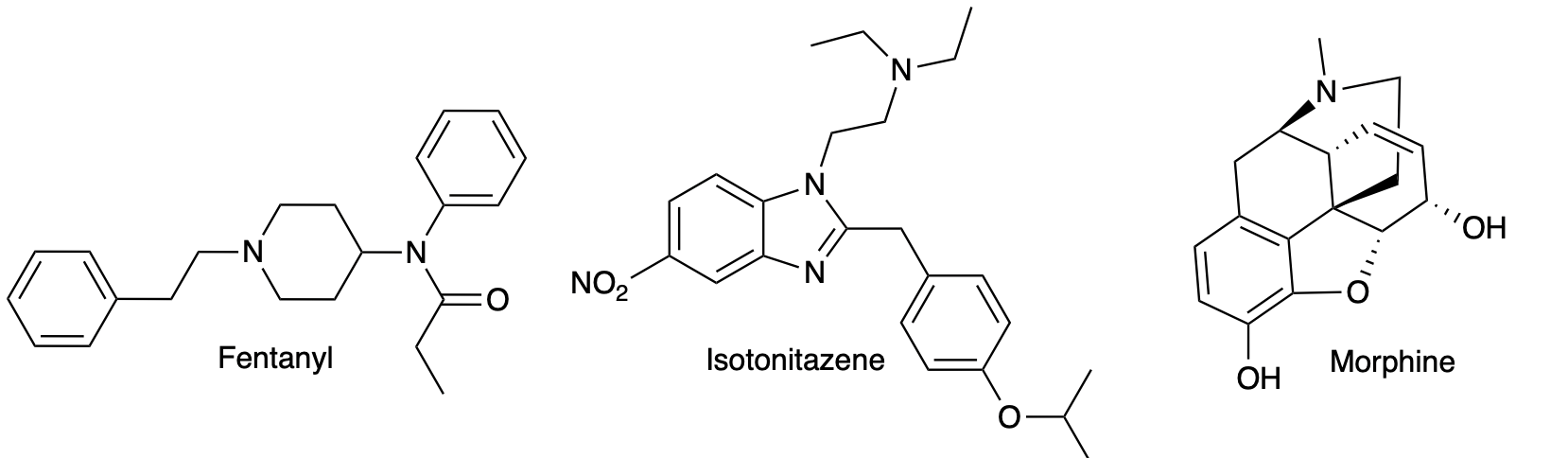

Is it possible that strict regulation of the chemicals used to make illicit fentanyl and its analogs encouraged the production of other illegal drugs, such as isotonitazene or clonitazene – members of the benzimidazole class of opioids? Since nitazines bear no chemical resemblance to either morphine or fentanyl, it is a given that they are prepared from a different set of chemicals (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Although fentanyl, isotonitazine, and morphine are all opioid receptor agonists, they have nothing in common chemically, so they must, by definition, be synthesized from completely different chemical building blocks (starting materials and intermediates).

DEA is behind the curve

Is it possible that making fentanyl precursors harder to get was in any way responsible for the uptick in nitazine overdose deaths? A look at the DEA List 1 restricted chemicals (2) suggests this is possible.

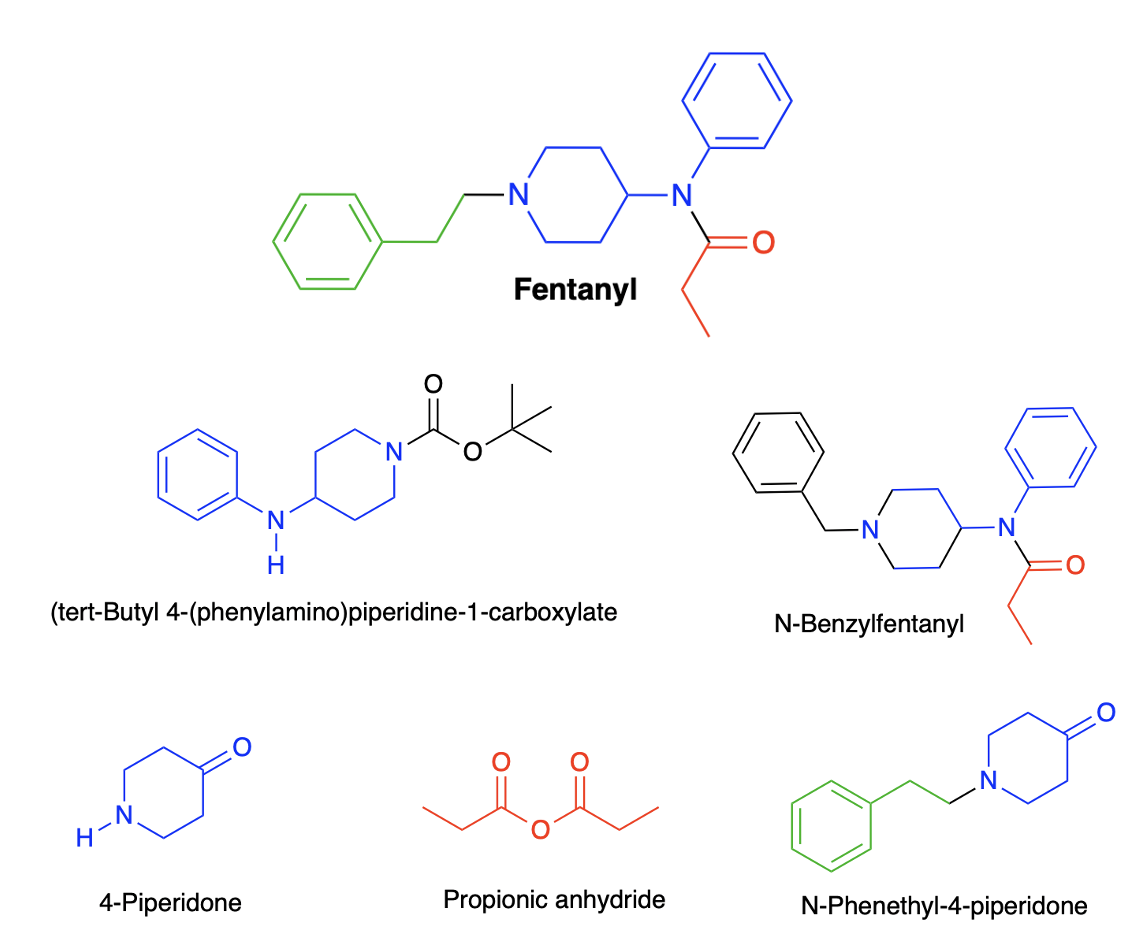

Of the 39 List 1 chemicals (3), five chemical reagents or intermediates are used to synthesize fentanyl (Figure 2). The colors of the fragments of fentanyl correspond to those same fragments in the chemicals used to make the drug. Although there are multiple ways to synthesize fentanyl, there can be little doubt that if the chemicals in Figure 2 are difficult to get, fentanyl production will suffer.

Top: The chemical structure of fentanyl. Bottom: Five chemicals defined by the DEA as List 1 fentanyl precursors.

What about etonitazene chemicals?

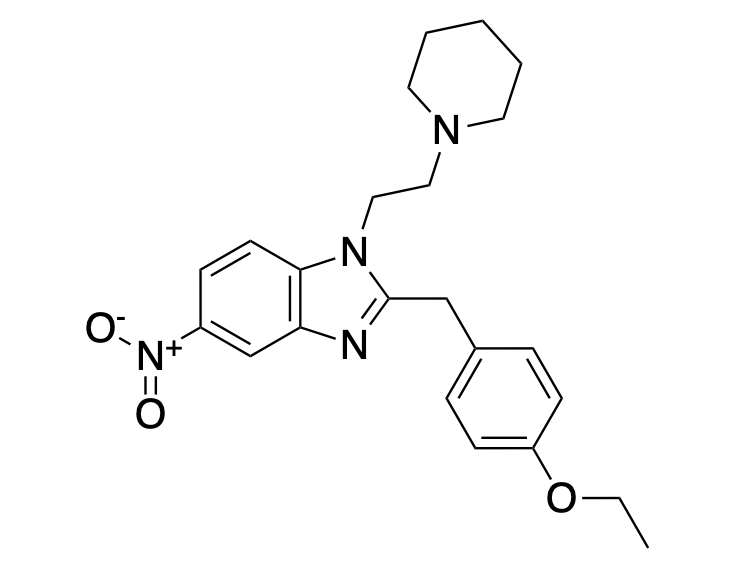

The chemical structure of etonitazene bears no resemblance to any fentanyl analog.

Even a brief look at the chemical literature (not to mention the chemical structure) makes it clear how different the structure and synthesis of fentanyl and nitazenes, e.g., etonitazene are. There are multiple syntheses in the literature for the preparation of etonitazene, a drug first made in the 1950s. From two of these synthetic routes, I picked out 10 chemicals that have been used to prepare the drug:

- o-phenylenediamine

- 4-nitro-o-phenylenediamine

- p-ethoxybenzyl cyanide

- 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene

- 2,4-dinitroaniline

- 1-chloro-2-dialkylaminoethane

- 1-amino-2-diethylaminoethane

- 2-(β-dialkylaminoalkylamine)-5-nitroaniline

- phenylacetonitrile (4)

How many of them are on the DEA List 1? Zero.

This means that any of the chemicals required to make etonitazene – only one of a series of highly potent nitazene analogs – can be ordered from chemical supply companies without regulation.

Only time will tell whether nitazene opioids will replace illicit fentanyl as the primary killer, much like heroin replaced prescription opioids and fentanyl replaced fentanyl. But it makes sense. Drugs like etonitazene are extremely potent (less is needed) and very easy to synthesize. Chemists who may switch to a deadlier drug will find all the supplies they need to do so.

Is this an atypical example of the "iron law" in action? It's certainly possible. Both precedent and the power of organic chemistry make it reasonable, if not inevitable.

NOTES:

(1) Brorphine is another opioid agonist, but it does not belong to any of the opioid classes I have discussed.

(2) According to the DEA: "These chemicals are designated as those that are used in the manufacture of the controlled substances and are important to the manufacture of the substances."

(3) The number 39 is not strictly correct. For example, piperidine, one of the List 1 chemicals, can be purchased as the free base (amine) or any of several salts, e.g., hydrochloride, hydrobromide, sulfate...

(4) It is nothing short of astounding that phenylacetonitrile, aka benzyl cyanide, is not on the DEA List 1, since it can easily be converted to phenyl-2-propanone (P2P) - one of the chemicals now used to make methamphetamine.