The initiative, the Million Hearts Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Reduction Model, asks physicians to evaluate the risk of future cardiovascular events (MI, death, and stroke) using the American Heart Association risk calculator and providing additional guideline-directed medical care – initiating or enhancing the use of statins to lower cholesterol, antihypertensives to control blood pressure, and aspirin to reduce platelet aggregation. [1] This model was part of an overarching initiative by CMS to reduce heart attacks and strokes by 7%, which they had concluded would make the costs revenue-neutral, balancing the incentives against healthcare savings. [2]

The Peer-Reviewed Study

516 organizations, practices with a median of 38 physicians, were randomized to provide the "model intervention" vs. their standard care for those at risk for heart disease. Given the incentives for treating high and medium-risk patients, more of them were enrolled in the treatment arm than the control. While the groups were quite similar, with a median age of 72, 58% male, and 7% Black [3], the treatment arm patients had lower Medicare expenditures and hospitalization before the study. The reporting period began in 2017; the median follow-up is 4.3 years. Remember, payments were based not on outcomes for the patient but on changes to their 10-year cardiac risk model.

- There was an absolute reduction of 0.3% in the probability of a CVD event (7.8% in the intervention group vs 8.1% in the control group)

- There was an absolute reduction of 0.4% reduction in CVD events and deaths (9.3% in the intervention group vs 9.7% in the control)

- “There was no significant difference in Medicare spending on CVD events between the intervention and control groups” [emphasis added]. There were no calculations of deductibles and out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries.

- Healthcare incentives, “model payments,” for risk reduction were 28% of the total model payments.

“This randomized pragmatic trial suggests that paying for risk assessment and reduction could improve outcomes of public health importance. However, high rates of model nonparticipation demonstrate the importance of calibrating payments to effort and reducing burden of data sharing.”

Careful readers will note the use of “suggests” not quite as positive as “shows.” And for a study that is, indeed, “pragmatic,” there is little mention of “high rates of model nonparticipation.” The authors saved the pragmatic, less spun data for their funders, CMS, not clinicians.

The Rand Report to CMS

The pragmatic data on the nuts and bolts of the program are found in the much fuller report to CMS by the Rand Corporation, that did this study.

Let’s begin with nonparticipation.

Let’s begin with nonparticipation.

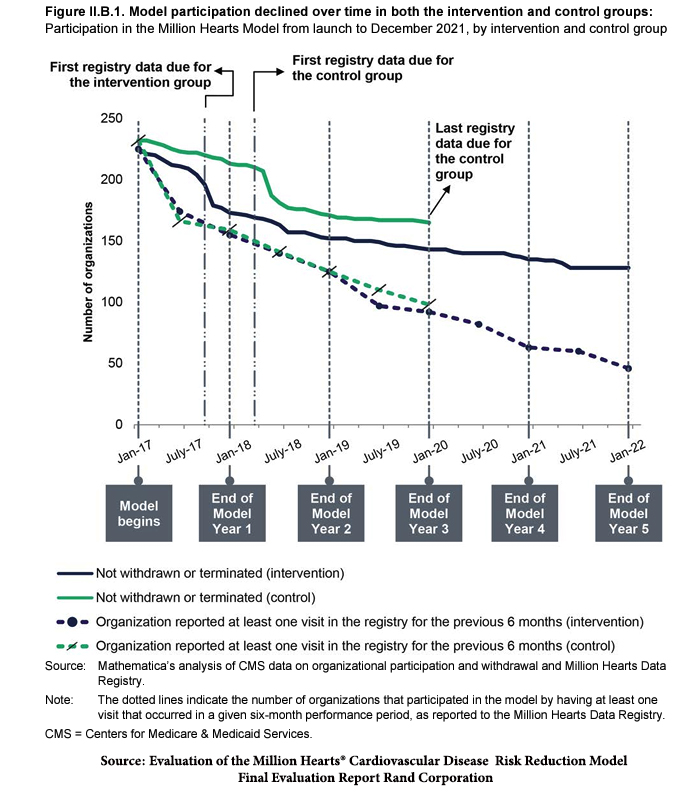

The health systems with the highest participation rate were the control groups – those not changing their care, just collecting some data. But look at the steep drop-off in participation when the only requirement, their data, was due. The participation rate among the intervention group was less throughout, and again, once the data was expected and the organizations discovered the effort required, participation declined steeply. At the end of the study period, 26% of organizations had formally withdrawn, and 47% had simply stopped submitting data – 73% of the total, a high rate of model nonparticipation.

One way we might think of this is that the cost of participation for the healthcare systems was more significant than their reward. This is even more of a concern because these systems had access to the much-vaunted electronic health records, so data collection should have been far more manageable; they are the source of “big data.”

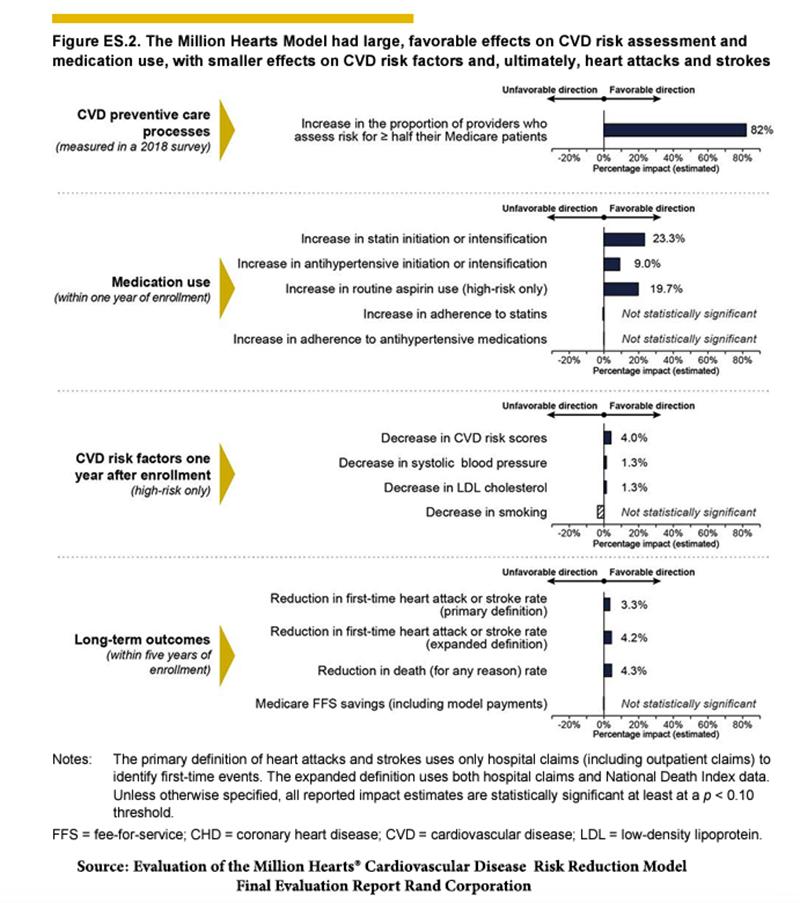

Then, there are a few interesting points within the dataset. The caption to the figure says it all. To be fair, the study's goal was to provide policymakers at CMS with information on how well incentives changed physician behavior. However, what should matter most in determining policy how well it incentivized physicians or whether it improved outcomes?

The greatest “improvement” was carrying out the risk assessment, which comes with a caveat. Only 52% of physicians in the control group and a statistically more significant 78% in the intervention group reviewed the scores.

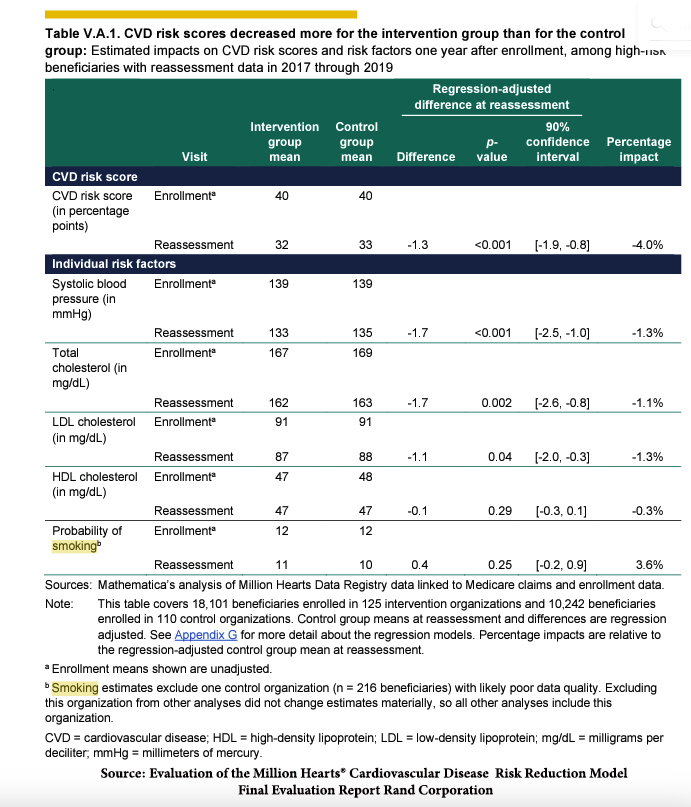

What about the risk factors that could be modified and improve cardiac risk scores? Specifically, providing  guideline-driven care in reducing LDL, hypertension, platelet aggregation, and smoking cessation.

guideline-driven care in reducing LDL, hypertension, platelet aggregation, and smoking cessation.

There were improvements in the prescription of all three classes of medications, which in turn explains the improvement of risk scores. But, prescribing medications alone is insufficient; the patient has to swallow them, and in general, the adherence to the use of antihypertensives and statins was 80%, and not improved by the additional visits to physicians among the study patients.

Smoking was the most resistant to change; in fact, there was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups in smoking cessation, and it was the modifiable variable that had the greatest impact on risk, which was to worsen the 10-year cardiac risk.

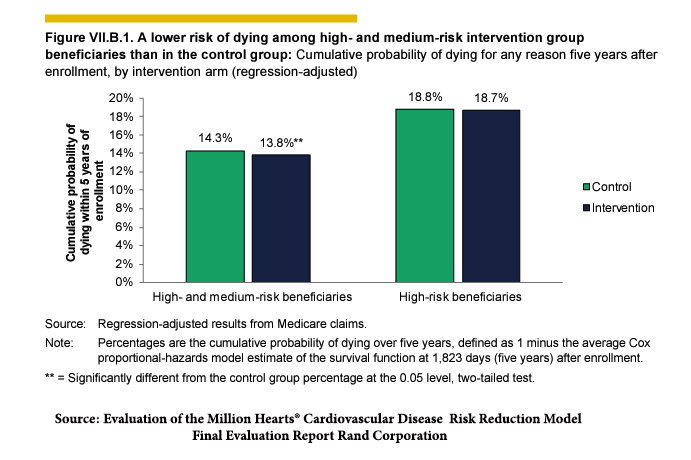

“Across outcomes, results were generally more favorable among medium-risk beneficiaries than high-risk beneficiaries, for whom differences between the intervention and control group were not statistically significant for first-time CVD events, combined CVD events and CVD deaths, or all-cause deaths.”

The use of the term “generally more favorable” is well-crafted wording. As the graph of the full report demonstrates, high-risk patients had no statistical improvement with this enhanced care – perhaps “too little, too late?” All of the benefits accrued to medium-risk patients.

The use of the term “generally more favorable” is well-crafted wording. As the graph of the full report demonstrates, high-risk patients had no statistical improvement with this enhanced care – perhaps “too little, too late?” All of the benefits accrued to medium-risk patients.

Finally, there is a question of costs. This is a CMS-centric study and initiative to reduce their costs, not yours. While the goal was to reduce CMS’s expenditures, the conclusion was that they did not increase expenses. They provided no data on costs to beneficiaries. What might they be?

The additional cost of a statin, aspirin, or antihypertensive is relatively small, and there was some additional out-of-pocket cost for co-payments to physicians. But we may not, as patients, be moved at all by cost; after all, smoking cessation, which represents savings, was barely moved at all by the intervention.

From a pragmatic view, there may be some advantages to improving preventative care for cardiovascular disease, but those benefits to the highest-at-risk are exceedingly small; to a large degree, they have made their “[hospital] bed and now must lie in it.” But for those with lesser risk, that “ounce of prevention can be worth a pound of cure,” provided as the researchers note, that we calibrate “payments to effort and [reduce the] burden of data sharing” – greater incentives and less oversight

[1] High-risk patients, those with a 30% or greater 10-year risk of an untoward cardiovascular event, were to receive 1) a discussion of their risk and development of an individualized care plan, 2) annual and additional follow-up roughly every four months for reassessment, which would include recalculating their 10-year cardiovascular risk.

[2] The payments to health systems could range from $0 to $120 per beneficiary annually based on a system that even I find too arcane to discuss.

[3] The researchers hastened to point out that the social construct we know as race was included “because Black race is associated with higher CVD-event risk in the US.”

Source: Effects of the Million Hearts Model on Myocardial Infarctions, Strokes, and Medicare Spending JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.19597