The peak load of COVID virions was established early in the pandemic. Peak loads occurred at essentially the same time individuals manifested symptoms. But a new study looking at infections during Omicron finds a different symptom-viral load timeline.

The research involved 348 individuals seeking evaluation for self-reported upper respiratory tract infection symptoms. None were COVID-positive within two weeks of enrollment. All underwent PCR testing using the nasal cavity search method we are now all acquainted with once enrolled. As a reminder, in polymer chain reaction (PCR) testing, the presence of antigen, in this case viral particles, is amplified until it is detected. Fewer amplification cycles reflect a more significant initial viral load.

The data gathered by the researchers characterized the number of PCR replications, Ct, with the self-reported onset of symptoms. The cohort was a bit more female, 65%, and young, with a median age of 39.2. They were concerned about COVID infections as 91% had been vaccinated or had infection-acquired immunity, and nearly 70% had tested for COVID and been found negative within the two days before study enrollment. Most presented with a cough, sore throat or runny nose – all non-descript symptoms that might be associated with COVID or influenza.

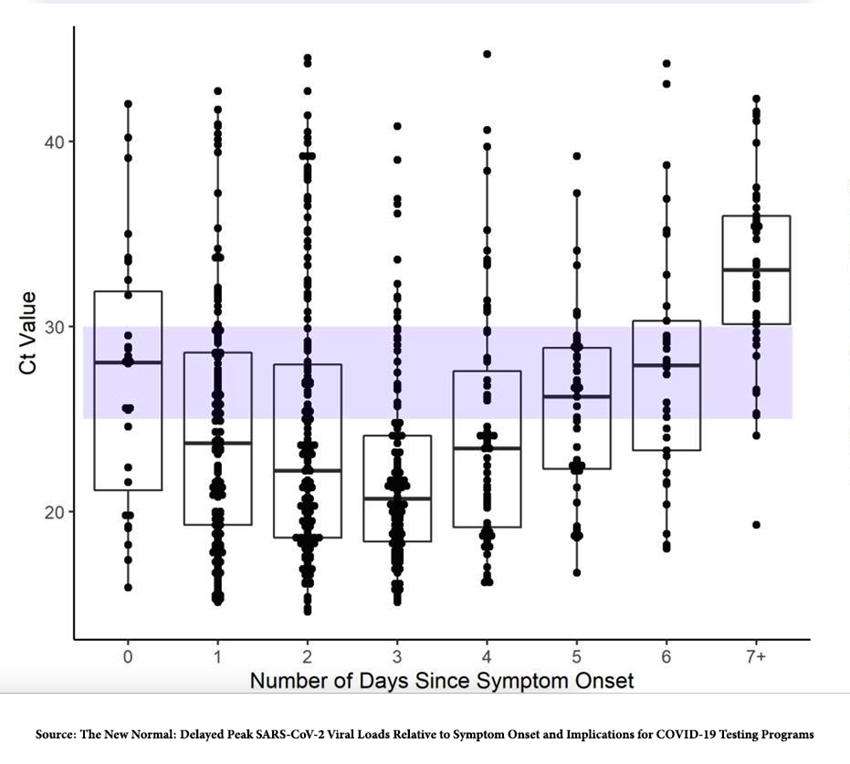

This box-and-whisker plot [1] demonstrates the viral load, as measured by Ct, and the time course of symptoms. The nadir, meaning the greatest viral loads, was identified on Day 4. The Omicron variant has been associated with diminished severity, so it makes common sense that it requires a higher viral load to cause symptoms to be manifested.

Several implications follow from these findings.

The spread of disease

In most instances, when we become symptomatic for a “cold,” we take some preventative measures. While not all of us will call in sick from work, why ruin a perfectly good “sick day” by being ill? We might cover our mouths when we sneeze or cough or limit our social contacts. Our emotional response of disgust is felt to be a built-in protection from communicable diseases. For the earliest variants of COVID, the peak viral load and perhaps the most significant risk of transmitting the infection to others occurred just before or at the time symptoms became manifest. We unknowingly transmitted the disease to others.

But the time course of Omicron is different. In part, that difference may lie in the still ill-defined concept of herd immunity; everyone’s immune response is more robust, and we do not develop as great a viral load as with the other versions. However, the study demonstrates that the greatest viral load occurs four days after symptoms manifest, when we have had time to take precautionary measures, or when evolution has conditioned us to avoid others.

Testing for COVID

PCR has the greatest chance of being accurate and avoiding false negatives when viral loads are greatest. Early in the pandemic, PCR testing at the time of symptom onset, when viral loads were highest, was 90-95% accurate. But, the time course identified by the researchers shows that is no longer the case, and viral loads are only beginning to rise. This may well lower the sensitivity of the same test to 60 or 80% - a negative test just is not as certain. That is part of why the CDC recommends a second PCR test 48 hours after a negative test, to catch the rising viral load that might have been missed.

Among the 348 participants, 74 did not have COVID at all; they had influenza, the seasonal flu. Interestingly, the viral load vs. onset of symptoms in this group matched those of early COVID – the onset of symptoms occurred at the peak of viral loads. That suggests that seasonal flu spreads through asymptomatic carriers to a greater degree than does the current COVID variants. It is an argument for those at risk to get an influenza vaccination because it is impossible to identify the “Typhoid Marys” amongst us based on symptoms.

Today’s COVID lesson in evolution and hubris I leave to the authors.

“In summary, our data remind us that viral load kinetics relative to duration of symptoms can change over time with exposure to an initially novel virus, and that data collected early in a pandemic should not be assumed to still apply in the months to years that follow.”

[1] The box-and-whisker plot contains a great deal of information.

Source: The New Normal: Delayed Peak SARS-CoV-2 Viral Loads Relative to Symptom Onset and Implications for COVID-19 Testing Programs Clinical Infectious Diseases DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciad582