Activist groups utilize a well-worn set of propaganda tools to turn the public against pesticides. These range from funding junk studies to buying favorable media coverage and filing endless lawsuits against chemical manufacturers. But all these routes of attack are enhanced by a ploy I call the "phony whistleblower gambit."

The archetypal phony whistleblower is a credentialed scientist, usually a former government official, who uses his reputation to help trial lawyers and environmental NGOs sell anti-pesticide scare campaigns to consumers. Supposedly an academic rebel, this person follows the science wherever it leads. Of course, “the science” inevitably leads to massive paydays for tort lawyers and harsh restrictions on vitally important chemicals.

Here’s a recent, real-world example of the phony whistleblower gambit from the Guardian, authored by journalist-turned activist Carey Gillam and funded by the billionaire-backed Open Society Foundation. Her target is the herbicide paraquat, currently the subject of thousands of lawsuits alleging that the weedkiller causes Parkinson’s Disease.

Let’s dismantle this Potemkin village one pasteboard at a time so you can see how the scheme works, and why it's so dangerous.

Don’t trust the EPA, says EPA scientist

According to Gillam, “federal regulators are discouraged from speaking up about potentially dangerous pesticides.” How does she know? Well, an EPA scientist told a major media outlet that EPA scientists are afraid to speak their minds:

Karen McCormack, a retired Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) scientist who spent 40 years with the agency … described a culture of ‘regulatory capture’ at the EPA and said that colleagues who spoke out in favor of more stringent regulations on pesticides were often sidelined.’

We've heard this story many times before; it's the classic progressive tale of corporate malfeasance and it doesn't stand up to scrutiny. The first issue is that McCormack’s resume is doing all the heavy lifting. She doesn’t substantiate a single allegation she makes about the EPA in Gillam's article. We’re apparently supposed to take it on faith that McCormack is telling the truth about her sidelined colleagues and the pesticide industry’s ability to “capture” the agency. If her former employer is so corrupt, McCormack should prove it. Her credentials and experience are irrelevant otherwise.

But the allegation is doubly absurd because McCormack is using her reputation as an EPA scientist who “conducted research on pesticides” for 40 years to undermine trust in the very same organization. She can't advertise her agency experience and assert that everyone else in the place is an industry shill or a fearful bureaucrat who approves pesticides "no matter how high the risk." Why believe someone who would work in such a sordid environment for four decades?

Ignoring real issues

Ironically, there is ample evidence that the EPA has succumbed to political pressure in the past, as my colleague Dr. Henry Miller has documented here. Contrary to McCormack’s allegation, however, the problem is the agency's willingness to collude with anti-pesticide groups, Miller explains:

There is a long and ugly history at EPA of what has been dubbed ‘sue and settle,’ or ‘regulation through litigation,’ whereby regulators encourage legal challenges by environmental activists to their regulatory decisions … That enables EPA to make concessions to the plaintiffs via settlements and consent decrees without the constraints of rulemaking and the scrutiny of the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

In recent years the EPA has conceded to activist groups in court on one pesticide after another, including the insecticides sulfoxaflor and chlorpyrifos and the herbicides dicamba, atrazine and paraquat. Many farmers have explained to EPA why these concessions are so devastating. Unnecessarily restricting access to paraquat and other weedkillers, for instance, can increase soil erosion, water pollution and herbicide resistance in weeds, one growers association pointed out in a public comment to the EPA.

Ultimately, this makes growing food for all of us more expensive and challenging. Sadly, farmers get far less attention than activists who lie without hesitation about pesticide safety.

Fibbing about paraquat

Let's take Gillam’s analysis of paraquat as an example of rampant dishonesty. She claims to have “exposed years of corporate efforts to cover up paraquat’s links to Parkinson’s disease, mislead the public, challenge published scientific literature and influence the EPA.”

But that’s just false. At least 85 studies–funded by governments, pesticide companies and nonprofits–have failed to produce evidence that the herbicide causes Parkinson’s Disease. Even workers at paraquat-manufacturing facilities, who have the highest exposure to the chemical, are no more likely to develop Parkinson’s than the general population.

When paraquat causes harm, it’s usually because someone deliberately misuses it (for example, in a suicide attempt) or doesn't follow the label instructions when applying it. The activist-friendly EPA adds that it has “found no dietary risks of concern associated with paraquat when it is used according to the label instructions.” That means the vast majority of people (who are only exposed to trace of amounts of pesticides through food) can't be harmed by the weedkiller.

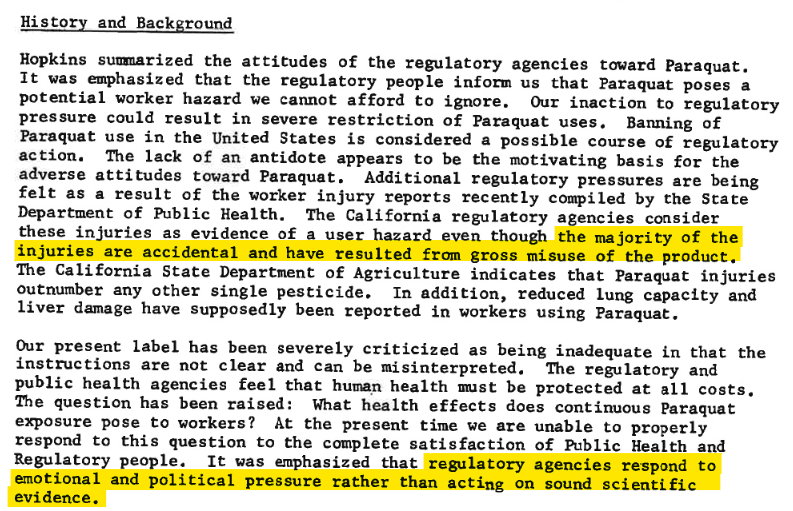

Gillam points to “secret files” from paraquat manufacturers Syngenta and Chevron to bolster her conspiracy, but this is just smoke and mirrors. When we read the documents themselves instead of relying on Gillam’s and McCormack's spurious allegations, we can see they contain much of the same information found in publicly available sources. Here’s one example from a 1974 Chevron memo, available on Gillam’s New Lede website:

Tragic consequences

Governments and corporations do evil things sometimes. True whistleblowers who call out real corruption provide an invaluable service, but that’s not what McCormack is doing. She’s helping dishonest activists like Gillam spread ideological nonsense that has devastating consequences.

Needlessly restricting the chemicals farmers use to grow our food leads to hunger, poverty and political instability—as Sri Lanka found out the hard way recently. Anyone who enables those horrifying outcomes deserve nothing but scorn.