Background

Lead poisoning was recognized as early as 2000 BC, and childhood lead poisoning was first described in 1892 in Australia, resulting in lead paint being banned from house paint in 1914. However, until the 1940s, most pediatricians believed that children who did not die after the initial phases of lead poisoning suffered no long-term effects. This changed with studies in the 1940s that showed that children who survived lead poisoning often had severe problems in intellectual function, and in the 70s through 90s with studies showing that behavioral problems, IQ deficits, and problems with attention and perception in children with low levels of lead that did not cause more severe symptoms.

One of the success stories over the last 50 years is removing the major sources of lead in air, drinking water, and paint.

In Drinking Water

Lead pipes were first installed in the U.S. in the 1800s and continued being installed through the 1980s. In 1991, the US issued a regulation, termed a treatment technique, for lead in drinking water. This regulation required water utilities to control the water’s corrosivity [1] but not the removal of lead water pipes.

This worked quite well for most water systems over the years; however, a few high-profile cases, including that in Flint, Michigan, demonstrated that lead in drinking water could still threaten communities.

The EPA’s regulatory treatment technique remained relatively unchanged until the issuance of the new Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) on November 30, 2023. It includes the following provisions:

- 100% lead pipe replacement within ten years.

- Improved tap sampling that better represents water that has been stagnant within the service lines and plumbing.

- The lead “action level” is reduced from 15 to 10 micrograms per liter.

- Additional outreach, including filters to consumers in water systems that are not yet fully compliant.

I have previously called for removing lead pipes in drinking water systems. According to the EPA, an estimated 9.2 million lead service lines provide water to communities across the US. But the American Water Works Association (AWWA), a non-profit scientific and education organization of water supply individuals, estimated it would cost $12,400 per lead service line replacement, compared to the EPA’s estimate of $6,154. Using AWWA’s estimate results in a total cost of more than $114 billion to replace all lead service lines.

In 2021, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, providing $15 billion for lead service line replacement and $11.7 billion of general Drinking Water State Revolving Funds that can also be used for lead service line replacement. But even using EPA’s lower cost estimate of $56 billion, these funds are insufficient to replace all lead service lines. With these costs, is it worthwhile to remove all lead pipes when controlling drinking water’s corrosivity can eliminate most lead in drinking water at minimal cost? While removing lead pipes is a step forward, our biggest problem remains lead in old paint.

In Paint

Lead was added to paint in the early 1900s to speed up drying, increase durability, maintain a fresh appearance, and resist moisture that causes corrosion. Over the years, the Federal government has taken several steps to reduce the hazard from lead in paint or paint chips – paint chips are the primary source of exposure for young children who ingest the chips resulting from peeling paint. These Federal measures include:

- The Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act (1971) prohibited lead-based paint in residences constructed or rehabilitated by the Federal government.

- The Residential Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act (1992) expanded the definition of lead hazards to include lead-contaminated dust and soil and outlined a national strategy to eliminate these hazards.

- The Renovation, Repair, and Painting Rule (2008) required the EPA to certify painting and renovation firms working in pre-1978 housing.

Although these regulations have been helpful, they have not removed the lead paint hazard.

Approximately 23 million housing units contain significant lead-based paint hazards, many in low-income areas. The number of homes with lead-based paint makes remediation very challenging, and many low-income communities lack the financial means to address this problem. In 2018, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that HUD needed to make major improvements to its lead compliance process and grant programs.

In the Air

Historically, the primary source of lead in the air was leaded gasoline exhaust with lesser amounts from industrial processes and aircraft. Tetraethyl lead was blended with gasoline to boost octane beginning in the early 1920s. In 1990, the Clean Air Act Amendments resulted in a final ban on lead in gasoline, effective in 1996. Lead in the air is no longer a significant source of exposure. The average maximum amount of lead in our air decreased 97.7% since 1977 (from 1.35 to 0.03 micrograms per cubic meter).

Lead and Our Children

The CDC recently lowered their screening level for further testing children for lead from 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood to 3.5 micrograms per deciliter of blood, indicating that most scientists believe that extremely low lead levels can cause health problems in children.

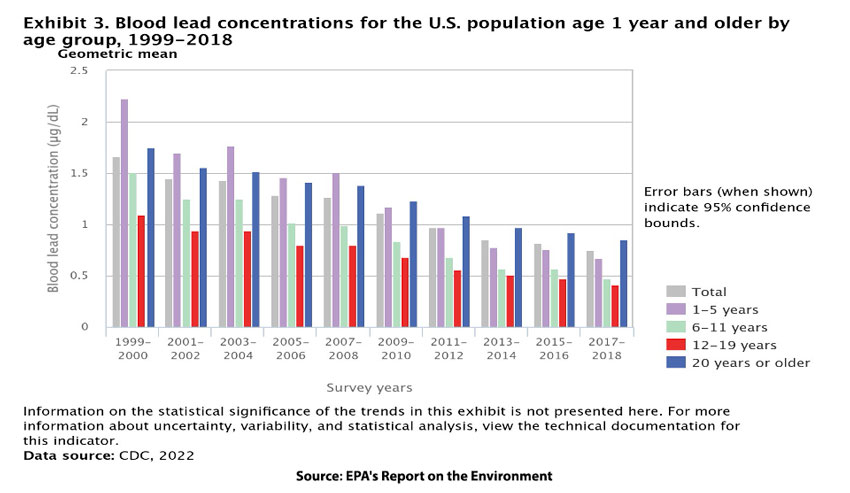

Lead concentrations have been decreasing in all age groups in the U.S. In 1976-1980, 88.2 percent of those aged 1-5 had blood levels greater or equal to 10 micrograms lead per deciliter of blood; today, only 5 percent of those one years of age or older have blood lead levels of 2.41 micrograms lead per deciliter of blood or greater. The CDC considers prevention of childhood lead poisoning one of ten great US public health achievements.

While removing lead pipes is a step forward, Congress must allocate additional funds to complete the job. Paint remains the remaining public health issue; there is a real need for public awareness and pressure, along with other funds, so communities with older housing get the attention and remediation they need to create a safe environment for all.

[1] This involves treating water so that it has a relatively high pH (more basic), which lessens the ability of the lead in pipes to leach into the water.

Sources: Control of Lead Sources in the United States, 1970-2017: Public Health Progress and Current Challenges to Eliminating Lead Exposure Journal of Public Health Management Practices DOI: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000889

History Of Lead Poisoning In The World Biodiversity Organization