Formaldehyde is important in many manufacturing processes; it is released when things burn, e.g., car exhaust and forest fires, and is slowly released from consumer products, including composite wood products and paints. Formaldehyde also occurs naturally in our environment and is produced by plants, animals, and people, making regulation extremely challenging.

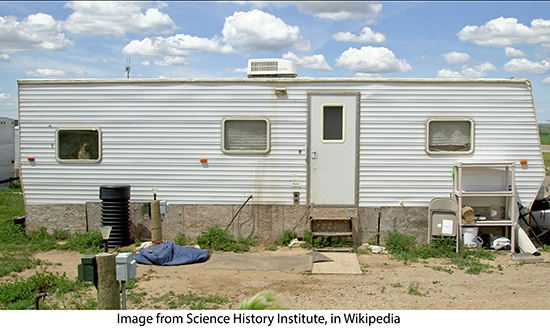

Formaldehyde became “an issue” in the 1980s when the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) found high levels of formaldehyde in mobile homes across the country. It came to the public’s attention in 2006 after evacuees from Hurricane Katrina reported health problems from living in trailers supplied by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). A 2008 report by the CDC identified high levels of formaldehyde in 42% of the trailers examined due to faulty construction practices and substandard building materials, causing breathing difficulties, eye irritation, and nosebleeds.

Formaldehyde became “an issue” in the 1980s when the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) found high levels of formaldehyde in mobile homes across the country. It came to the public’s attention in 2006 after evacuees from Hurricane Katrina reported health problems from living in trailers supplied by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). A 2008 report by the CDC identified high levels of formaldehyde in 42% of the trailers examined due to faulty construction practices and substandard building materials, causing breathing difficulties, eye irritation, and nosebleeds.

Multiple federal agencies, including the EPA, considered exposure to formaldehyde from the FEMA trailers and other sources to cause cancer. However, the evidence was far from certain and has since been shown to be scientifically flawed. In 2010, ACSH pointed out that EPA was promoting baseless fear over cancer from formaldehyde exposure. In 2022, both Dr. Michael Dourson, an ACSH Board of Scientific Advisor, and I discussed how EPA’s conclusions that formaldehyde causes cancer are scientifically flawed.

Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Risk Assessment

Under TSCA, EPA must determine whether a chemical presents an unreasonable risk of injury to human health. EPA prepared a draft risk assessment for formaldehyde that examined human exposure to formaldehyde from industrial, occupational, and consumer activities through breathing indoor and outdoor air and skin exposure. EPA evaluated 62 “conditions of use” that can produce formaldehyde and can be controlled under TSCA, including manufacturing of formaldehyde, processing, and manufacturing of articles and products, including composite wood products, plastic used in toys, and various adhesives and sealants.

EPA did not consider natural sources of formaldehyde, such as forest fires, trees, and wood chips, which constitute approximately 25% of the total formaldehyde concentrations in the environment, or formaldehyde from secondary formation [1], which can result in up to 75% of formaldehyde concentrations in air, as “conditions of use” since they cannot be controlled under TSCA. However, they factored them into the risk assessment by including them in the evaluation regarding the exposure concentration of formaldehyde, which constitutes an unreasonable risk.

The EPA concluded that formaldehyde presents an unreasonable risk of injury to human health for:

- Unprotected Workers – from eye irritation after short-term exposure and diminished lung function after long-term exposure from breathing formaldehyde. While the EPA is “aware that many employers do take measures to protect the safety of workers in their facilities,” it has made these estimated risks because “the EPA cannot guarantee that in all cases, personal protective equipment is provided and worn."

- Consumers – from eye irritation after short-term exposure to consumer products containing formaldehyde.

However, what is more critical and frequently unstated are the risks the EPA did not consider unreasonable. Formaldehyde does not pose an environmental risk because it is short-lived in water, sediment, or soil due to its physical and chemical properties. For people, they found that it was not a risk in

- Drinking water because people will not be exposed since it does not persist in water.

- Outdoor air, even for those living within a half mile of a releasing facility, because natural and secondary sources exceed sources releasing formaldehyde.

- Indoor air, because the greatest risk is in new home construction from new hardwood floors, wallpaper, and other products and the concentrations vary widely and are substantially reduced within two years, presenting limited long-term risk.

- Long-term consumer use over the long-term because exposures vary greatly and cannot be separated from indoor air exposures.

Cancer Risk

In what may be the most stunning and overlooked part of this assessment, the EPA did not conclude that formaldehyde posed an unreasonable cancer risk. Even with extremely conservative cancer human health benchmarks, the EPA found that the risk of developing cancer from formaldehyde exposure was negligible for the general population.

For each of the 62 conditions of use, the EPA compared measured or modeled data on formaldehyde exposure with “safe levels” or human health benchmarks. EPA then factored in the amount of formaldehyde formed naturally or from secondary reactions. If the measured or modeled data and naturally formed formaldehyde exceeded the health benchmark, the EPA concluded there was an unreasonable risk.

The EPA used cancer risk estimates for nasopharyngeal cancer from their 2022 Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Toxicological Review of Formaldehyde. As I discussed, this IRIS review is very controversial and remains the subject of litigation regarding the review process.

While the EPA’s IRIS risk assessment concludes that there is “evidence that formaldehyde inhalation causes nasopharyngeal cancer, sinonasal cancer, and myeloid leukemia in exposed humans given appropriate exposure circumstances,” none of the 62 conditions of use in the TSCA risk assessment are “appropriate exposure circumstances.” In fact, the appropriate exposure conditions to cause cancer must be so high and unrealistic that the EPA did not even consider it in its assessment. The TSCA risk assessment concludes that the risk from formaldehyde is only to unprotected workers and consumers who use large amounts of formaldehyde-containing products.

I commend the EPA for considering formaldehyde's natural and secondary formation in this risk assessment. This should be incorporated into other risk assessments, including their latest flawed ethylene oxide emissions regulations. Will the EPA show real leadership and reexamine these conflicting areas with the EPA where they have declared formaldehyde causes cancer, and will they partner effectively with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and other agencies to implement the results of this risk assessment in a common-sense approach? Now that the EPA recognizes that the primary threat is not cancer, the Agency may move forward to address the actual risks from formaldehyde.

[1] Secondary formation of formaldehyde occurs when chemicals in the air, such as those from air pollution, undergo chemical reactions to form formaldehyde.