Kids and parents, and millions of other fans, return to Major League ballparks this week for the start of the 2018 season, a fun and joyous time for people all over the country. Yet, at the same time, this occasion will mark something else much more morose: the beginning of a six-month stretch when unsuspected patrons sitting near the field are maimed by dangerously fast line drives.

Baseball is a game of statistics. And some statistics tell us that this season, on average, between 1,500 and 2,000 fans in Major League parks will be struck by an unavoidable, screaming foul ball, with many victims being left with lifelong disabilities or impairments like brain damage or vision loss.

With 2,430 games scheduled to be played before October's postseason, statistically, the estimated rate of injury will be nearly one per game. Yes, someone watching the action will be injured at nearly every game, some of them badly, requiring hospitalization.

Worse, the ugly truth is that your city's big-league team could completely eliminate any chance of its fans suffering horrible, disfiguring injuries. Because when we set aside management's lip service and incremental gestures done in the name of safety, the bottom line is that Major League teams have very little financial incentive to protect their fans from this very real and recurring threat.

This is due to the game's blanket legal immunity on the books for more than a century – known as the "Baseball Rule." While it exists it nearly-completely shields teams from liability, and it provides assurances that they'll rarely ever have to pay for the physical and emotional damage resulting from a baseball, traveling at speeds up to 110-mile-per-hour, smashing into a fan's head. And that's the case because when a fan purchases a ticket – which, over time, has effectively proved in the courts to be a binding contract – the fine print on the back states that the ticketholder relinquishes the right to sue, which judges have consistently upheld in favor of defendant teams.

It's this wholesale lack of liability and financial disincentive that's prompted an associate professor of business law and ethics, among others, to call for the abolition of the Baseball Rule.

"Although MLB has taken steps to increase the levels of fan protection in recent years, the time has come for courts to dispense with the Baseball Rule," writes Nathaniel Grow, from Indiana University's Kelley School of Business, "and instead hold professional teams strictly liable for their fans' injuries, forcing teams to fully internalize the cost of the accidents their games produce."

That increased protection Mr. Grow referenced includes teams extending protective netting down the first- and third-base seating areas to the far end of each dugout, adding to the existing screening directly behind home plate. (Incidentally, the origins of this screening came from the team's limited obligation associated with the Baseball Rule, where the courts reasoned that fan protection was required in the "zone of danger," or the seats directly behind and near home plate.)

That increased protection Mr. Grow referenced includes teams extending protective netting down the first- and third-base seating areas to the far end of each dugout, adding to the existing screening directly behind home plate. (Incidentally, the origins of this screening came from the team's limited obligation associated with the Baseball Rule, where the courts reasoned that fan protection was required in the "zone of danger," or the seats directly behind and near home plate.)

In fact, in the aftermath of a terrifying incident at Yankee Stadium last September (see adjacent photo) in which a two-year-old girl was maimed, 16 of MLB's 30 teams announced they would install the extended netting.

The girl, whose first name was withheld by her father, Geoffrey Jacobson, had her eyes swollen shut, she suffered multiple facial fractures and had bleeding on the brain. And, horrifyingly, an imprint of the baseball's stitches appeared on her forehead.

Now months later, without a mandate from Major League Baseball but acting on its recommendation issued over two years ago, all teams have voluntarily decided to provide the extended netting. That's very good news, and that should be recognized. But apparently, it took an innocent toddler's unspeakable injuries to tip the scales and to get teams to finally do what they had long resisted: altering the unimpeded view of fans who purchase the most expensive tickets.

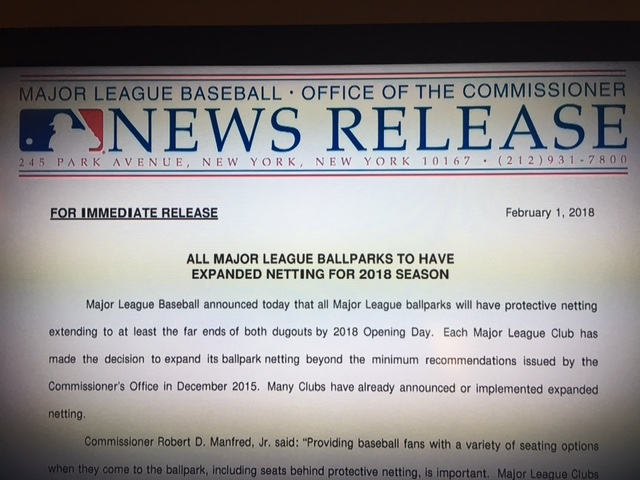

Baseball announced in a statement last month that all ballparks "will have protective netting extending to at least the far ends of both dugouts by 2018 Opening Day. Each Major League Club has made the decision to expand its ballpark netting beyond the minimum recommendations issued by the Commissioner's Office in December 2015."

While that's a significant safety improvement, there remain more prone fans close to the action where netting doesn't extend. And the only protection – which is legal – shields the teams, not those fans.

While that's a significant safety improvement, there remain more prone fans close to the action where netting doesn't extend. And the only protection – which is legal – shields the teams, not those fans.

The Baseball Rule was established in 1913 when the ballpark environment was completely different from what exists today. Back then, and in the decades to follow, attending a game was the sole attraction and fan distractions barely existed. Today, every MLB stadium has gigantic video boards and electronic tickers, constantly encouraging fan interaction; nearly every adult fan brings their cellphone with them, upon which the Internet and email is available; selfies and picture taking are ubiquitous; and most, if not all, stadiums provide free Wi-Fi to enhance the fan experience through the team's own social media sites, further increasing the chances of in-game distraction.

Add to that, many new stadiums built since the early 1990s were constructed with seating closer to the field, to get the fans to better connect with the action. Then there's access to a wide array of food, and of course alcohol, which clearly serves to undermine crucial reaction time.

But honestly, it's not as if you'd be completely safe if you never took your eyes off the batter: Someone in the stands sitting 60 feet and six inches from the batter's box – the exact distance between the pitcher and home plate – would have four-tenths of a second to react to a foul ball headed directly at them.

Finally, to put it another way, last year Major Leagues batters were hit by pitches on 1,739 occasions, 884 times in the American League and 855 times in the National League. These pitches were thrown at roughly the same speeds – but over a much shorter distance – as the batted foul balls, which injured nearly the exact same number of unsuspected fans.

And despite the ball whizzing just inches past them, the players in the middle of the action were arguably in a safer place than those unlucky fans in the stands. That's because, on balance, the players' injuries were nowhere nearly as devastating as the ones suffered by ticketholders.

It's been over 100 years. The ballpark environment has changed significantly, and the time has come for teams to protect their fans. The Baseball Rule has got to go.