Today's Wall Street Journal article entitled "Overdose Deaths Likely to Fall for First Time Since 1990" will certainly garner a lot of attention and will almost certainly be followed by a nauseating display of credit-grabbing. There will be many interpretations of the meaning of the data from Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts, just issued by the CDC. Here are some of mine.

"[D]ata predict there were nearly 69,100 drug deaths in the 12-month period ending last November, down from almost 72,300 predicted deaths for 12 months ending November 2017."

This single statement has multiple problems.

- Those numbers are predicted; they could change. The CDC writes "Provisional counts are often incomplete and causes of death may be pending investigation."

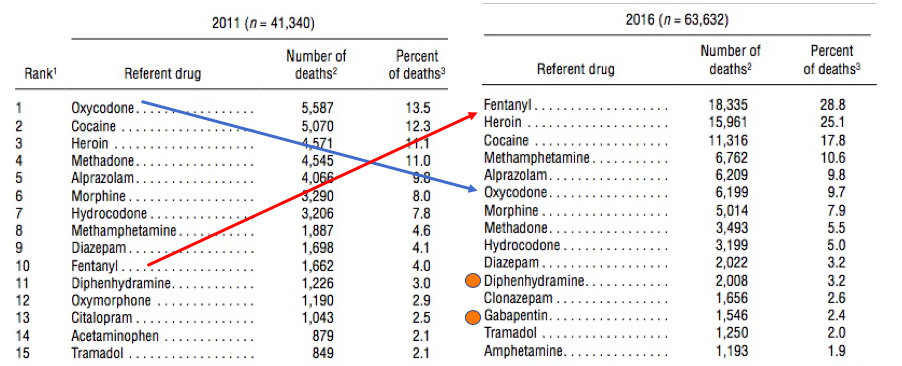

- As it has done all along, the CDC has lumped together all drugs to come up with these figures. As I wrote last December, the restrictions placed upon prescription pills have had an interesting impact (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Between 2011-2016, despite a significant drop in prescriptions, oxycodone deaths remained roughly constant while five drugs, especially fentanyl and heroin, rocketed to the top of the list. Note that both diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and gabapentin (Neurontin) joined the list, the two of them together accounting for more than 50% of the deaths caused by oxycodone. Source: National Vital Statistics Reports

- So, the decrease of ~3,000 overdose deaths, if it's real, could be caused by drops in any of these drugs, or drugs not even on either list.

The WSJ article emphasizes that one factor in the drop in deaths is the availability of Narcan.

"When asked why fatalities in the Pittsburgh area fell 41% to 432 last year—the lowest level since 2015—Allegheny County Chief Medical Examiner Karl Williams said: “In a word, Narcan.”'

Here's another possibility: So many people have died from illicit fentanyl (and fentanyl analogs) that there are fewer addicts left to overdose. They have already died.

Members of the chronic pain community have long talked about the "genocide" of people in pain. While I don't believe for a minute that our opioid policies, as ghastly as they have been, were based on any conscious attempt to murder pain patients, it is certainly possible, if not likely, that an "unintentional genocide" occurred, caused by the flight of both drug abusers and users from pills to street drugs as pills became harder to get. (1)

"Overdoses have killed roughly 870,000 people during this nearly three-decade rise, with particularly heavy tolls in the last several years, CDC data show."

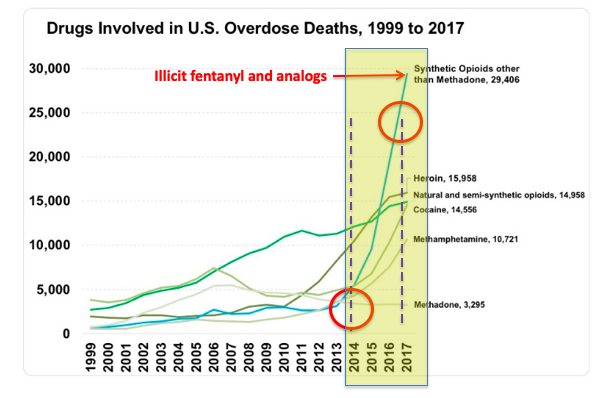

And why might that be the case? Perhaps this?

Figure 2. What has happened in the last several years is quite clear. Fentanyl and its analogs, and heroin are responsible for particularly heavy tolls, not prescriptions, something that has been painfully obvious - to anyone who would listen.

"...Ohio, long an epicenter for the fentanyl crisis, saw overdose fatalities fall about 24% to 3,694 last year... The fact that a highly-potent variant called carfentanil hit the state hard from mid-2016 to mid-2017 played a role by driving the death rate higher in those years, local coroners have said.

Assuming that the numbers hold up and there really were fewer deaths in 2018 in 2017, the decrease was driven primarily (probably entirely) by "fentanyls," and had nothing to do with the fatally flawed efforts of the "pill crusaders." If there has been a reduction is it because fewer people took fentanyl or they took a less deadly analog. Which has pretty much been the entire story all along.

In reality, I'm betting that, with the exception of better treatment of acute overdoses, little or nothing has changed. We are still in the same heroin/fentanyl crisis that took off like a rocket a decade ago.

James McDonald, the medical director of the state health department of Rhode Island - a state that has aggressively pushed efforts to combat fatal overdoses said: “There’s no one around here celebrating anything.”

He's got that right.

NOTE:

(1) This is alluded to in the article. Magdalena Cerda, director of the new Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at NYU-Langone said that "some of the most vulnerable people have already been killed."