Most popular news stories about diet soda follow a predictable formula that goes as follows. Hoping to lose weight, Americans have consumed vast quantities of Diet Coke and other sugar-free drinks for years, but overlooked evidence suggests diet soda is surprisingly harmful.

This well-worn narrative is wrong in almost all its particulars, and that's because it's not based on science, but ideology. Let's examine a recent example to see why. According to an August 6 MSN story:

[T]here has been a debate over the true health effects of diet drinks. Health experts have also raised questions about the use of artificial sweeteners … [O]ne study suggested that the low-calorie drinks could still increase an individual’s risk of developing diabetes and obesity. Numerous groups of researchers also found no evidence that diet soda can provide any direct health benefits aside from reduced sugar intake.

First, the fact that a single study suggests diet soda could increase your risk for diabetes and obesity doesn't mean anything. We shouldn't forget that confounding variables often invalidate seemingly sound research. For instance, a 2014 study found that diet soda consumption increased women's heart disease risk. Buried at the bottom of the paper, though, was a serious problem: women with the elevated risk were more likely to be overweight, smoke, and have high blood pressure—confounding variables. There are also high-quality clinical trials showing that people lose weight, and thus reduce their cardiovascular disease risk, by switching to diet drinks. These carefully conducted experiments complicate the diet-soda-will-kill-you narrative.

More importantly, there has been “a debate” about everything in science. Experts conduct research and argue with each other until the correct answer to a question emerges. It's a messy, tedious process, but it's also how we learn about the world around us. The media generally miss this important point in a rush to churn out eye-grabbing headlines. Yes, scientists disagree sometimes. So what? If the evidence is inconclusive, journalists should report that to the public. But they shouldn't say that experts disagree, then insinuate that their preferred conclusion is probably correct.

A little logic goes a long way

It's unlikely that diet soda boosts anybody's risk for obesity and diabetes. People get fat because they eat too much, which often leads to diabetes. Since these sugar-free drinks contain no calories, a little deduction tells us that Diet Coke probably can't be blamed for poor metabolic health. Many studies supporting the diet soda-disease link exist. But as science writer Tamar Haspel explained in a recent story, that research gets less compelling the closer you look:

"[C]lick on over to PubMed, the repository of scientific journals, and look. Check the research on humans. Ignore anything industry-sponsored. You’ll find plenty of lists of potential harms, but once you weed out speculation and focus on evidence, you don’t find scary."

Moreover, it's misleading for MSN to claim that diet soda doesn't “provide any direct health benefits.” Granted, these products aren't loaded with vitamins, nor do they cure any malady. But obesity is a socially stigmatizing condition that can set people up for very serious diseases. If drinking diet soda helps avoid those outcomes–and good evidence supports that conclusion–it provides a clear health benefit.

What's really going on?

So why is this scary story about diet soda constantly rehashed despite the evidence? Calorie-free drinks, like the plant-based Impossible burger and many other popular foods, enable consumers to make healthier choices without radically altering their lifestyles. The media commentators, politicians and academics who have made careers out of trying to radically alter the public's choices find this inconvenient, so they rail against these “processed foods” as a threat to human health.

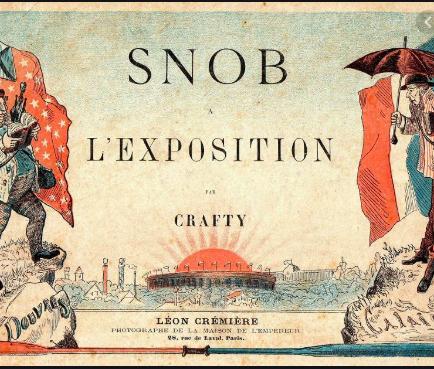

This backlash may be rooted in a kind of food snobbery that gained traction in the 1980s. According to University of Michigan food scholar S. Margot Finn.

“[M]iddle- and upper-class people began to fixate on gourmet food, weight-loss dieting, natural foods, and ethnic cuisines … Much of this shift in attitudes toward food was undertaken in the name of health and the environment. But its primary function … has been to enable people of a certain social class to distinguish themselves from the unwashed masses.”

Fortunately, none of that ultimately matters. Our food choices should be based on evidence and personal preference. There's no scientific reason to think sugar-free drinks are harmful, so excuse me while I go get a Coke Zero.