The study looks at hospitalized patients predominantly in the US along with Spain, China, and South Korea. The roughly 300,000 patients received a combination of 3455 different repurposed and adjunctive drugs. Because there is no specific COVID-19 antiviral, repurposed in another way of saying “off-label” use. This graph, adapted from the study, shows the drugs, grouped using different colors for each organ system being treated, each dot a specific drug, at the major US study sites – this is what the kitchen sink looks like.

Globally, the top five repurposed to treat COVID-19 were anti-infectives and antiparasitic agents, including hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and ivermectin. But as with many infectious diseases, the additional physiologic stress of COVID-19 resulted in deficiencies and complications that, in turn, required adjunctive agents. The commonly used agents included those directed against clotting, bacterial infection, ulcer prevention, and cytokine storm. And we threw in steroids, Vitamins (especially C and D), and ACE inhibitors [1].

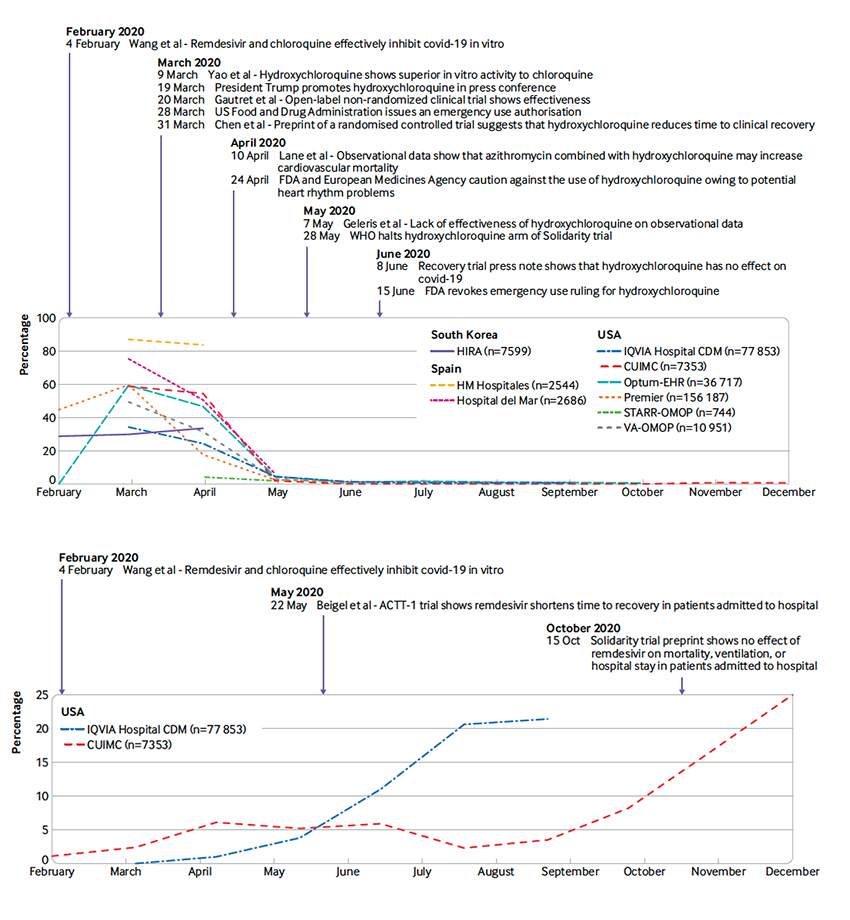

The use of these drugs varied by country and over time, adding to the complexity. These two graphs depict the rise and fall of hydroxychloroquine along with the rise of remdesivir – both annotated with important clinical milestones.

A few highlights

A few highlights

- “During March and April 2020, more than 50% of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 were prescribed hydroxychloroquine.”

- “Remdesivir, another highly publicised antiviral, was only used in two databases, and in less than 25% of patients.”

- “Corticosteroid use in general appeared to increase slowly during the study period.”

- “The use of anticoagulants in our study was higher than expected.”

Despite a specific coordinated effort, the information on what did and didn’t work spread rapidly, primarily through pre-prints and video, two very different channels for medical communication.

“The observed heterogeneity and rapid changes in drug use go hand in hand with the infodemic associated with covid-19.”

This brings us to a second, inter-related study, looking at the research that fueled our clinical behavior.

Evidence versus eminence-based medicine

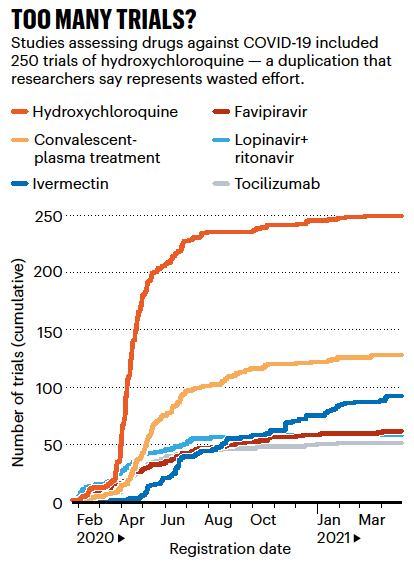

The era of “do as I say,” when authority was based upon eminence, has rightly given way to “follow the science,” evidence-based medicine. That does seem well and good - until all hell breaks loose, then it becomes difficult to identify the evidence. Just as clinicians frantically empirically sought the best treatment, researchers sought the “right proof,” initiating 2900 clinical trials. As these authors point out, most were too small to yield statistically reliable insight.

The era of “do as I say,” when authority was based upon eminence, has rightly given way to “follow the science,” evidence-based medicine. That does seem well and good - until all hell breaks loose, then it becomes difficult to identify the evidence. Just as clinicians frantically empirically sought the best treatment, researchers sought the “right proof,” initiating 2900 clinical trials. As these authors point out, most were too small to yield statistically reliable insight.

And because we simply do not have global collaboratives, many studies were duplications of the efforts of others.

If you compare this graphic on the right with the timeline for hydroxychloroquine’s use, you see how the normal temporal relation of clinical trials and everyday use flipped. In the pandemic, clinical trials supporting or disproving “efficacy” lagged far behind clinical use – and why treatment recommendations changed or “flip-flopped” over time. This is what evidence-based care looks like when it is rushed.

If you compare this graphic on the right with the timeline for hydroxychloroquine’s use, you see how the normal temporal relation of clinical trials and everyday use flipped. In the pandemic, clinical trials supporting or disproving “efficacy” lagged far behind clinical use – and why treatment recommendations changed or “flip-flopped” over time. This is what evidence-based care looks like when it is rushed.

The confusion over data providing our best, let alone any evidence, was further fueled by over 410,000 articles generated by May of 2020 from those trials and other reports. No one could read, or assimilate, all of those studies. The volume of clinical trials, primarily small, short, and ill-designed, made it necessary to scream your work to be heard through any type of Internet soapbox you could find. Unfortunately, much of that effort did little but “rearrange the deckchairs on the Titanic.”

Why is it so hard to say we didn’t do our best under novel, stressful circumstances? Why must we ascribe blame? In part, it has to do with that beauty of 20-20 hindsight; everything is so much clearer in the rearview mirror. In part, I suppose, at least for physicians, it is guilt. Do No Harm is so simple in words, so complex, at times, in deed.

There is no one at fault, no ill intent, no grand conspiracy, and certainly no flip-flop of recommendations for “what to do” – despite what our putative political leaders might suggest deflecting from their responsibilities and failures. We have done the best we could. We can and will do better. But without adjusting for an increasing global population, we have saved roughly 95% more lives in treating the COVD-19 pandemic than we did with the Spanish Flu 100 years ago.

[1] ACE inhibitors are a type of blood pressure medication. As you may remember, the COVID-19 virus attaches at an ACE site which was the proximal rationale for its use.

Source: Use of repurposed and adjuvant drugs in hospital patients with covid-19: multinational network cohort study BMJ DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n1038

How Covid Broke The Evidence Pipeline Nature DOI: 10.1038/d41586-021-01246-x