"Cleaning, integrating, and managing the uncertainty in chaotic real data is essential for reproducible science and to unleash the potential power of big data for biomedical research.”

But frequently, the exact details necessary to unleash biomedical research raise privacy concerns. HIPAA rules seek to protect our privacy but have been used as a hurdle in the quest for transparency in regulatory science – the science we use to underpin government regulations. With the increasing ubiquity in databases, keeping deidentified data unidentified is exceedingly difficult. A new study looks at our preferences for how our personal information is used and by whom. Would it come as a big surprise that what we want for our data and the laws surrounding data use are at odds?

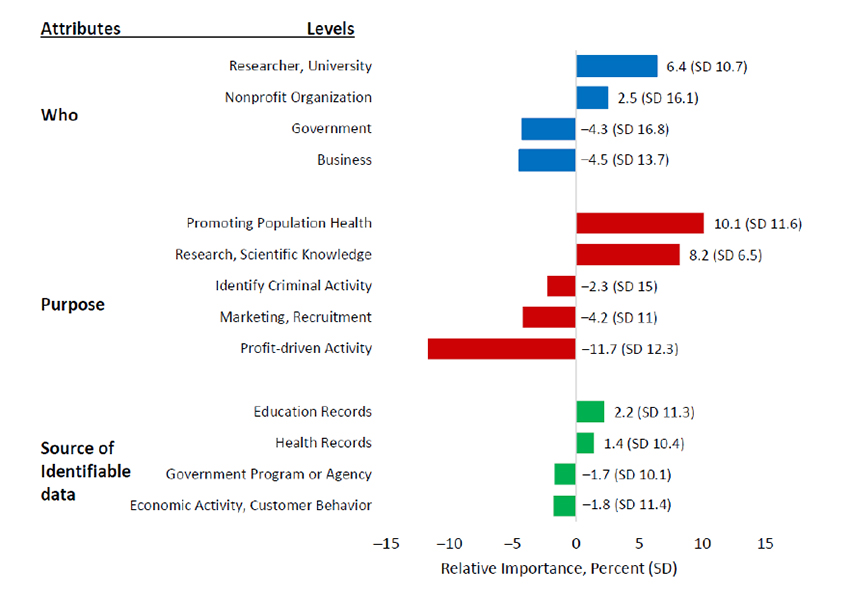

The researchers constructed 72 scenarios varying

- who wanted our data – academics, non-profits, government or business

- for what purposes – research/knowledge dissemination, public health, marketing, profit-driven activity, and criminal activity

- and the data source – education, health or government records or our economic activity and behavior

They asked a representative sample of adults, 500 or so, their preferences. Here is an example.

The sample was chosen to reflect our national age, gender, regional, income, educational, and ethnic demographics. Because of the researchers’ specific interest in healthcare, the sample was also reflective of insurance coverage, chronic conditions, and interactions with healthcare in the last year – they took great pains to create a panel that would reflect our national thinking on the use of personal data.

The sample was chosen to reflect our national age, gender, regional, income, educational, and ethnic demographics. Because of the researchers’ specific interest in healthcare, the sample was also reflective of insurance coverage, chronic conditions, and interactions with healthcare in the last year – they took great pains to create a panel that would reflect our national thinking on the use of personal data.

- Participants were most comfortable when data was used to promote public health or scientific research, particularly by academics or non-profits, and it used their educational or health records

- Participants were least comfortable when data was used for marking or other for-profit uses, by business or government

- Public health and research was always viewed positively irrespective of who was doing the research

- Marketing and for-profit uses were nearly always viewed negatively.

Our Paradoxical Thinking

Our Paradoxical Thinking

Even though we believe our educational and health data should be used to improve our lives, HIPAA and the lesser-known Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act create significant and often inexplicable barriers to their re-use in research and regulatory science. As the researchers point out, our cellphone numbers can be used for COVID-19 tracking, but treatment records related to substance abuse are not available to researchers and have hampered a greater understanding of the opioid epidemic.

The use of data for marketing and other for-profit activities, something we say we least prefer, is ubiquitous. Even the most recent changes to our privacy laws, where we are explicitly asked our preferences, seem to make little difference. Who among us has turned off “marketing cookies” for every website we visit? Or read terms of service where the right to market your data is buried deep on page 18?

In their discussion, the researchers felt that our data concerns might be categorized as altruistic, for the public health or enhancement of knowledge; or as self-serving, those profit-making, marketing activities. But in that categorization, how do you fit using our personal data to identify criminal activity? We seem conflicted.

We can certainly make a strong case for identifying criminal activity as a public good; many feel it is a public health issue – “in the lane” for medical attention when it comes to guns, domestic violence, and drug use. But since crime may lead to punishment, others may view this data use as more self-serving, especially when a given data point, say home address, may be confounded by income or ethnicity and result in inadvertently discriminatory behavior. All good research raises more questions than it answers. I would find it interesting to look again at criminal activity data framed as a public health or legal issue to see how our views may or may not change with the framing.

I have written on several occasions on the attempts by the Trump administration to make regulatory science more transparent and available for review. Among the objections from academic researchers is the possibility of disclosure of personal medical information. But that objection seems, at least based on this survey, to fly in the face of the desires of the general public. There are many ways to safeguard our health privacy and make this data available to a larger audience. Doing so might enhance our trust in government, something currently in short supply.

"Importantly, these results support a close re-examination of the absence of public health and research data use exceptions in US laws. It is clear that the US public strongly prefers using data to promote population health (as compared to other legal data uses); yet, few laws allow this kind of exception.”

Source: US Privacy Laws Go Against Public Preferences and Impede Public Health and Research: Survey Study Journal of Medical Internet Research DOI: 10.2196/25266