Human nutrition periodically undergoes profound transformations. Salt, once scarce and costly as both a seasoning and a preservative, became a central economic commodity, even lending its name to cities such as Salzburg. With technological advances, expanded production, and the discovery of new deposits, salt became cheap and ubiquitous, allowing governments to use it as a public health tool through iodization to prevent goiter.

Another potential dietary revolution followed the accidental discovery of saccharin, the first non-caloric sweetener, by Constantin Fahlberg. According to Fahlberg,

“Before going home at night, I carefully washed my hands. I was very surprised at dinner when I noticed a sweet taste on them as I brought a piece of bread to my mouth… I ran back to the laboratory and tasted all the beakers, flasks, and plates on my bench until I finally found the sweet taste in the contents of one of them.”

Subsequent sweeteners, including cyclamate, aspartame, and acesulfame-K, were also discovered serendipitously. Over time, non-sugar sweeteners (NSS) proliferated and were incorporated into processed foods. Between 2007 and 2019, global per capita NSS availability increased by 36%, particularly in beverages and in high-income countries. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2009–2012 indicate that approximately 40% of U.S. adults consumed NSSs, mainly through diet beverages.

More recent evidence suggests this trend may be reversing. A 2025 study, analyzing 10 NHANES cycles, found that age-adjusted NSS consumption increased until the mid-2000s but declined between 2017 and 2020, both in the general population and when stratified by chronic disease status. Whether this represents a sustained shift remains uncertain.

Proposed explanations include reduced preference for intensely sweet products, substitution with “natural” alternatives, and growing concern over potential adverse health effects, such as diet-related cardiovascular and metabolic non-communicable diseases, and weight gain.

In 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO), based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials and prospective observational studies, issued guidance on NSS.

“WHO suggests that non-caloric sweeteners should not be used for weight control or to reduce the risk of chronic non-communicable diseases” [1].

A recent study published in Nature Metabolism challenges the WHO’s position, although its findings require careful qualification.

The Nature Study

Before discussing the study, it is important to note that it is part of SWEET (Sweeteners and Sweetness Enhancers: Prolonged Effects on Health, Obesity, and Safety), a project funded by, “a consortium of 29 pan-European research, consumer and industry partners,” [2] examining the long-term benefits and risks of replacing sugar with sweeteners in relation to public health, safety, obesity, and sustainability.

The study sought to identify short- and long-term risks and benefits related to weight, disease biomarkers, and the gut microbiome. To address these questions, the authors conducted a randomized clinical trial evaluating the long-term effects of combining low- or non-nutritive sweeteners (S&SEs) in foods and beverages with a healthy, reduced-sugar, ad libitum diet in overweight or obese adults. The trial also included children and adolescents, but only for analyses of weight and cardiometabolic outcomes.

Participants were assigned to either the S&SEs group or a control group (reduced sugar without sweeteners). The study ran for one year across four European centers. The initial sample included 341 adults and 38 children. For microbiota analyses, a subgroup of 137 adults who completed the study was selected. During follow-up, 138 adults and 16 children were excluded or dropped out, yielding a final sample of 203 adults and 22 children.

- In the analysis of all participants (intention-to-treat analysis), individuals lost approximately 6.5 kg over one year. The S&SEs group lost 1.6 kg more than the sugar group. Among participants who completed the study, the difference was similar but not statistically significant.

- Greater reductions in BMI, total cholesterol, LDL, and HDL were observed in the S&SEs group. No significant changes were seen in diabetes or cardiovascular markers.

- Among children, BMI decreased in both groups, with no significant differences between them.

- The study found no differences in the number, richness, or diversity of gut microbiome species. However, it observed marked shifts in overall composition, with most changes involving short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)–producing microbes, which were generally more abundant in the S&SEs group.

- Machine-learning analyses indicated that baseline microbiota composition distinguished responders from non-responders for changes in HbA1c and weight regain in the S&SEs group. These microbial differences seem to persist.

Both groups maintained significant weight loss after one year, with slightly better maintenance in the S&SEs group. The observed weight loss was nearly twice that reported in the WHO systematic review (0.71 kg), likely reflecting differences in study design.

The study has several limitations. Most notably, the high dropout rate (40%) reduced statistical power. 25% of energy intake estimates were below estimated energy requirements, suggesting underreporting. Because intake was assessed at discrete time points, there is no guarantee that sugar or sweetener consumption remained stable throughout the study or that changes did not occur primarily on the days immediately preceding assessments. Unmeasured variables and behavioral changes, such as the Hawthorne effect, may have influenced dietary patterns in both groups. Complete blinding was not possible, so bias during measurement cannot be completely ruled out.

While the authors emphasized the six-month benefits of sweeteners, these effects largely disappeared by 12 months when compared with the sugar group; even so, the study provides valuable insights when properly contextualized. When consumed within established limits and as part of a balanced diet, sweeteners appear safe in the long term and do not seem to harm the gut microbiota.

Another key, although somewhat obvious, point is that consuming non-nutritive sweeteners alone does not cause weight loss. By the end of 12 months, both groups lost weight, and although the S&SEs group lost slightly more, the difference reached significance only among participants with higher adherence to the dietary protocol. Sweeteners’ principal value may lie in supporting dietary adherence, enabling the replacement of sugary foods and beverages with low- or no-calorie alternatives, supporting a reduced-calorie diet. However, the presence of sweeteners does not make a product inherently healthy; many foods containing these sweeteners also include less nutritious ingredients that may be harmful when consumed in excess.

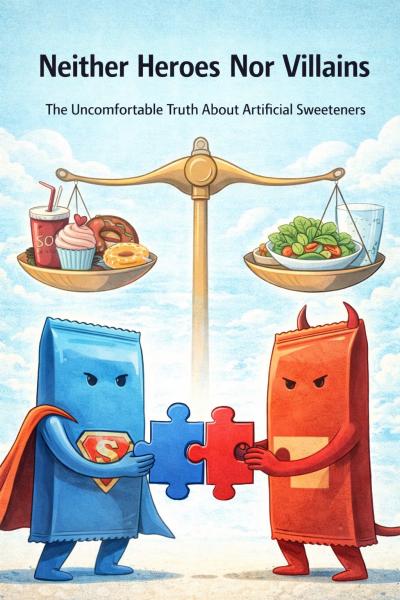

Taken together, these findings highlight an uncomfortable truth about artificial sweeteners: they are neither the heroes some hoped would solve obesity nor the villains others feared would threaten public health. They are context-dependent tools that can help reduce sugar intake and support dietary control, but are insufficient as standalone interventions. Ultimately, health outcomes depend far more on overall dietary patterns and consistent healthy choices than on sweeteners themselves.

[1] “Conditional recommendations indicate that the guideline development group has lower certainty that implementation will provide more benefits than harm, or that the expected benefits are small.”

[2] Four of the 22 authors declared conflicts of interest, including funding or fees from companies such as Nestlé, Unilever, and the American Beverage Association. Conflicts of interest do not invalidate results but warrant caution when interpreting findings and their limitations.

Sources: Effect of sweeteners and sweetness enhancers on weight management and gut microbiota composition in individuals with overweight or obesity: the SWEET study. Nature Metabolism. DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01381-z