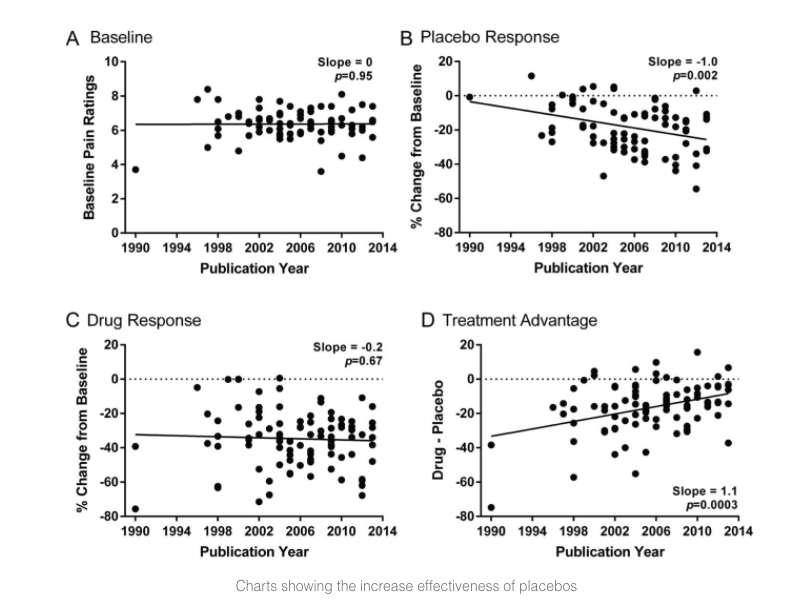

OK, that last line is a bit of clickbait; placebos themselves are not necessarily becoming more effective, but newer active medications may not be much more effective than the older ones, which means we might need to reconsider how we determine active medication efficacy.

The researchers looked at randomized controlled trials of medications for neuropathic pain for roughly 20 years. They considered 80 studies involving 92 drugs. A 16% advantage of active medications over placebo was reduced to 9% over those years – the cause:

“We find that placebo responses have increased considerably over this period, but drug responses have remained stable, leading to diminished treatment advantage.”

Age and gender did not seem to play a role; non-caucasian participants seemed to be more responsive to placebos. But the real problem appeared to be the design of the studies. Specifically, larger study populations  from more diverse geographical areas in the US and with more extended studies. Interestingly, the half-life response to placebos is markedly greater than the half-life response to pain medications, so longer studies favor placebo. Studies from outside the US did not show the same marked response to placebos, but they also did not demonstrate increasing study populations or study length, suggesting that indeed these are pertinent factors in designing drug efficacy trials.

from more diverse geographical areas in the US and with more extended studies. Interestingly, the half-life response to placebos is markedly greater than the half-life response to pain medications, so longer studies favor placebo. Studies from outside the US did not show the same marked response to placebos, but they also did not demonstrate increasing study populations or study length, suggesting that indeed these are pertinent factors in designing drug efficacy trials.

Many factors frame the placebo response in addition to the ones elicited in this study. Prescribing a placebo involves the physician, patient, and placebo itself. Studies have shown that the mode of placebo delivery can enhance its effect – injections are taken “more seriously” than rubbing on some lotion.

The message sent by the physician can impact the placebo response. The more competent, convincing the pitch, and the more trustworthy the source of those words, the more efficacious a placebo may become. Of course, the receiver interprets the message, which is impacted by their history of care and level of understanding. Children are more susceptible to the placebo response than adults. A robust positive history with the physician impacts the trust in the message.

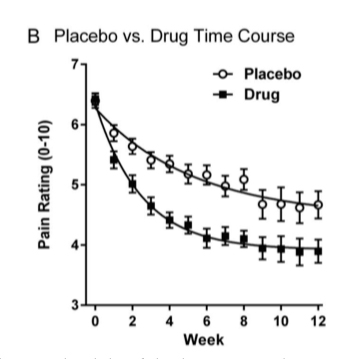

The researchers asked an important question. The placebo response should decay over time; after all, the expectation of pain relief is not actually being met. Without a reward, why continue the behavior? They suggest that the expectation of relief innervates our brain in anticipation of an effect, in the same way, but perhaps not to the same degree as active medication.

There is a mind-body connection – everything our mind knows was learned from its body and senses. There is still much to learn about placebos; for instance, is the placebo effect as strong in telemedicine as it is with a trusted source?

Source: Increasing placebo responses over time in US clinical trials of neuropathic pain Pain DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000333