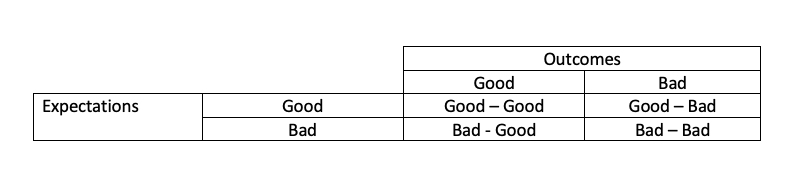

Let’s begin with a simple chart, comparing our expectations to our outcomes, with two choices, good or bad.

I learned about this chart discussing surgical complications and deaths during my training, but it remains a valuable means to analyze any retrospective consideration of our expected versus actual outcomes. Expectations are the surgeon's hoped-for result, and while we always hope for the best, sometimes we know it isn't in the cards - the patient will do poorly no matter what we do. Outcomes are the result of our care. A good outcome is a satisfied, restored patient; a bad outcome can be any of several complications, including death.

I learned about this chart discussing surgical complications and deaths during my training, but it remains a valuable means to analyze any retrospective consideration of our expected versus actual outcomes. Expectations are the surgeon's hoped-for result, and while we always hope for the best, sometimes we know it isn't in the cards - the patient will do poorly no matter what we do. Outcomes are the result of our care. A good outcome is a satisfied, restored patient; a bad outcome can be any of several complications, including death.

- Good Expectations – Good Outcomes: We are doing our job and doing it well. We expected a good result and got it. These were not patient cases presented at a morbidity and mortality (M&M) conference.

- Bad Expectations – Bad Outcomes: Here, we discuss why we initially took on the case. Often, we can blame it on the family or patient who wanted “everything done.” It's always some outside pressure that forces our hands.

- Bad Expectations – Good Outcomes: These cases are a time for a victory lap. But there is often an element of luck in these cases, so inappropriate pride at M&M would only draw attention; no one’s work is flawless. So victory laps are disguised as “interesting cases.”

- Good Expectations – Bad Outcomes: These are the cases that are grist for the M&M mill. Depending upon your interlocutor, you can present the facts and "beg" for mercy – something that is usually in short supply. Or you might describe a series of “unfortunate moments,” mixed with an overly optimistic judgment that led to your patient and now your downfall. The oral history of M&M conferences, as retold by the residents in the spotlight, often were war stories of the blaming and shaming that took place. “Dr. Dinerstein, why are you gambling with this man’s leg?”

I mention this because much of the early, unthoughtful, retrospective analysis of our societal response, both individual and institutional, to COVID-19 follows a similar pattern. Let me share a few examples.

The decision by Governor Cuomo to as quickly as possible return hospitalized nursing home patients to their respective nursing homes. The prediction that these patients would overwhelm available hospital beds was a bad expectation. The too-early return of patients that still could transmit the virus and reinfect more at the nursing homes was an admittedly bad outcome. Here are the thoughts of Dr. Zucker, then New York’s Health Commissioner and surrogate for the Governor, as reported by CNBC.

“Zucker said on Friday that, at the time, New York’s coronavirus hospitalization rate was growing “at a staggering pace” and capacity in the state’s intensive care units was running thin. By allowing the residents to return to the nursing homes, it helped protect the health-care system from collapsing, he said.” Outside pressure of rapidly diminishing hospital capacity, “made them do it.”

Consider the decision by President Trump to authorize Operation Warp Speed (OWS) and develop and deploy a vaccine within months despite a long history of this requiring years. That such a feat could be accomplished in so short a time was a bad expectation. Here is a headline from Stat:

“Operation Warp Speed promised to do the impossible.”

OWS was announced in mid-May 2020, and 17,000,000 doses were distributed by early January 2021 – 8 months. President Trump did take the victory lap,

“Operation Warp Speed is unequaled and unrivaled anywhere in the world, and leaders of other countries have called me to congratulate us on what we’ve been able to do….”

And predictably, especially in politics, that resulted in increased scrutiny, for example, the Business Insider headline:

“at least 75 lawmakers bought and sold stock in companies that make COVID-19 vaccines, treatments, and tests.”

That includes both sides of the aisle and those for and against vaccines. Not to worry, all members reported that others, including their spouses, were in charge of their investing; no pillow talk here.

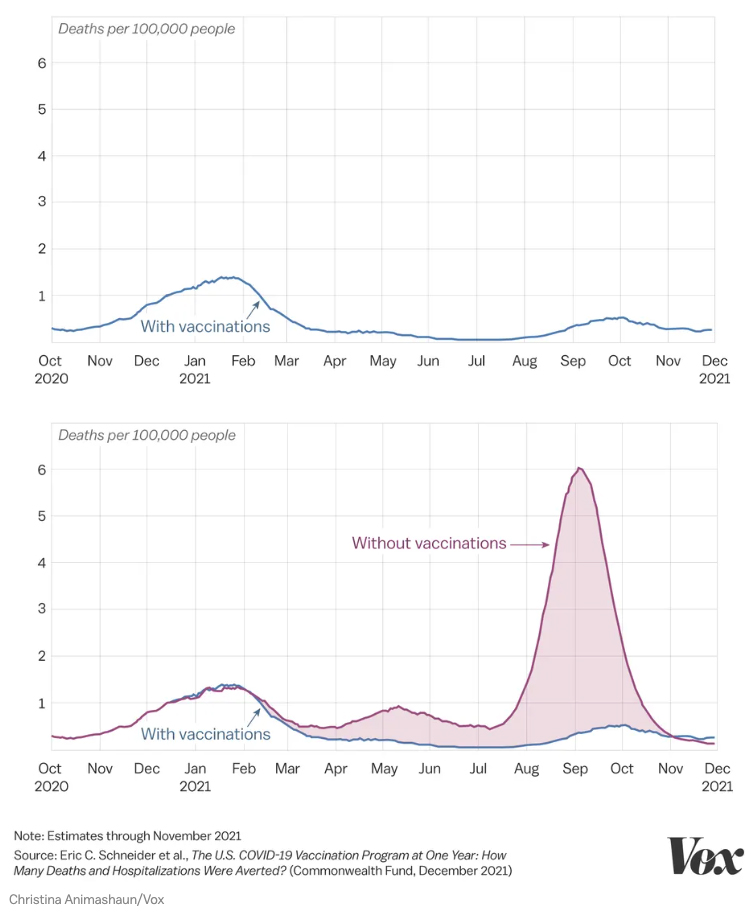

As I said earlier, good expectations coupled with good outcomes are rarely discussed. That has been the case here too. Those articles are alive and well in the medical literature but rarely reach the mainstream media. Here is a graph from Vox.

There is little doubt in the scientific community that vaccines prevented severe disease, but that was the expectation.

There is little doubt in the scientific community that vaccines prevented severe disease, but that was the expectation.

Finally, there is the category of shame and blame – good expectations and bad outcomes. We could consider many of Dr. Fauci’s statements and the subsequent amendments as the novel COVID-19 went against expectations.

“Dr. Anthony Fauci said the country could reach a level of population immunity in which the virus is no longer "dominating" people's lives. "That's entirely conceivable, and likely, as a matter of fact," President Biden's chief medical advisor said Tuesday on "CBS Mornings."

As I have written, as the data changed, so did Dr. Fauci’s opinion – your political orientation determines whether this is a flip-flop or simply a reconsideration. Also, the concept of herd immunity was based on measles which promotes a more durable immunologic defense and shows little mutation, two properties that we now know COVID-19 does not share.

There are so many other examples; consider the Great Barrington Declaration. They, too, based their recommendation on the concept of herd immunity,

“They argued that this policy would more readily lead to “herd immunity” that would ultimately protect the old and infirm.”

But they wished to apply it in a more strategic and focused manner to hopefully lower the economic costs of the pandemic. Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, one of the authors of the declaration, readily discusses his war wounds,

“I’ve had to revisit and rethink every aspect of my life, and there have been some very tough periods,” he said. “This is our crucible.”

Playing the Doctor Card

As it turns out, my surgical training prepared me for aspects of life that I had not anticipated. Having my shares of “moments at the podium” and suffered “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” I am not as quick to judge as I once was. I have learned that the best of plans can rapidly go south, and there is little you can do to stop the slide. It is easy to comment with hindsight, even easier when you have never really experienced one of your decisions resulting in the death of a patient in your care.

Very few of the commentators who speak of what we should and should not have done have actually made life and death decisions for someone right in front of them physically and temporally. They should be more humble. As we continue to try and understand our pandemic response, we should remember the works of Rene Leriche, a French vascular surgeon.

“Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray - a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.”

We need to show compassion for ourselves and our opponents. In most instances, we did what we thought was best.