Some context

Appendicitis was once a lethal disease, in the range of 85% of individuals who also had a perforation. Reducing that case fatality rate to negligible was one of surgery’s first triumphs. Antibiotics played a supporting role. But a few years ago, physicians treating diverticulitis had a new thought. Diverticulitis is an inflammation of abnormal “outpouchings” of the large intestine and, from a pathophysiological point of view, is essentially “appendicitis” in the large intestine. Medical management of diverticulitis begins with antibiotic therapy, not surgery. A rising tide of physicians believes appendicitis is managed just as well with antibiotics as the knife. There are a series of ongoing studies testing that belief, and at this juncture, treating selected cases of appendicitis initially with antibiotics has proven “non-inferior” to surgical management.

In the current study, researchers were interested in whether the patient's beliefs of the efficacy of antibiotic therapy before they began treatment affected their outcomes. Their data came from the Comparison of Outcomes of Antibiotic Drugs and Appendectomy trial (CODA) – the same study that showed that antibiotics were “non-inferior.” One thousand five hundred fifty-two patients were randomly assigned to treatment by surgery or antibiotics; the current study looks at a subset of those treated with antibiotics who expressed their belief about the efficacy of antibiotics before they began treatment. All participants were shown a video or read a pamphlet explaining the outcomes and risks of their participation.

Of 776 patients treated primarily with antibiotics, 425 were unaware of their randomized treatment before completing a questionnaire regarding their faith in antibiotic therapy. This was the study group: mean age 38.5, 65% male, 45% Hispanic, 62% White, 7% Black, and 5% Asian. Roughly a quarter were “unsure” of the antibiotic’s efficacy, half were “intermediate” – plus-minus, and the remaining quarter assured of the antibiotic’s complete success.

- Increasing signs (objective findings) and symptoms (subjective findings) of perforation, a significant complication of appendicitis, and diverticulitis resulted in those in the antibiotic arm of the CODA trial undergoing an appendectomy. This occurred in 20% of patients in the antibiotic-first group. For those unsure of antibiotic therapy, the rate of appendectomy was 28%; for the intermediate, the rate was 19%; and for the supremely confident, 14%.

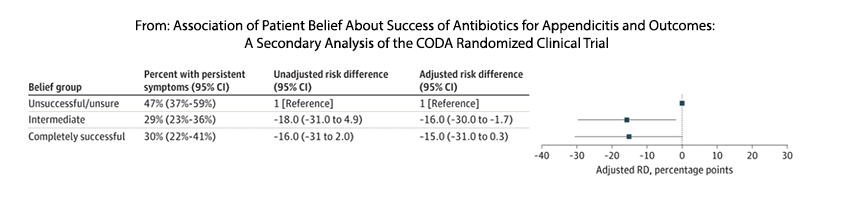

- The degree of belief was also associated with those “patient-reported persistent signs and symptoms.” The overall persistence of symptoms was 33% over 30-days. For the unsure, 47% experienced persistent symptoms, and for those intermediate and confident 30%.

What is the underlying mechanism?

Good question. As the researcher report, “it remains to be determined.” We might best attribute it to a placebo effect. A deeper look into the data does make that suggestion.

The table above shows patient-reported persistent symptoms. The intermediate and “true” believers reported fewer symptoms. At least two persistent symptoms, abdominal tenderness and pain are significant determinants of the need for surgical intervention. They also are somewhat subjective. Pain and perhaps to a lesser degree tenderness are "in the mind of the beholder" so it is certainly possible that those with greater faith "experienced" less of these subjective findings.

An accompanying editorial had this to say,

“Many molecular-level interactions must be accounted for in order to identify the determinants that are causally responsible for the observed clinical effect. These include the attitudes of the physicians, nurses, family members, etc, the pheromones they emit and share with one another, how these transferred signals are received and responded to, and how this giant “interactome” mechanistically influences outcome.”

I would not be as harsh; in fact, I am unsure whether the “attitudes of the physicians” can ever be meaningfully expressed as molecular-level interactions. This seems to be a weak (at best) linkage; as an old-school clinician, I am more willing to ascribe the findings to a patient's faith in their physician's treatment plan. The reductionists can continue to look for molecular interactions.

Source: Association of Patient Belief About Success of Antibiotics for Appendicitis and Outcomes A Secondary Analysis of the CODA Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Surgery DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.4765