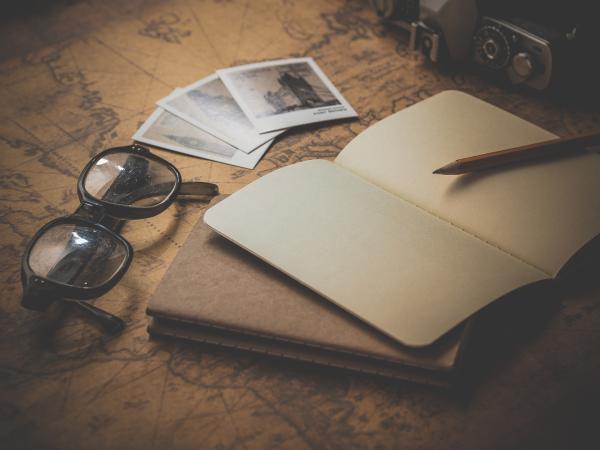

If you have the opportunity to read early scientific papers, and in this case, you need only go back to the 50s, they had a more conversational tone, for the pronoun conscious, more I or we than a silent absence of any pronoun at all. Over time that was replaced by a more structured style, introduction, methods, results, and discussion, which initially improved the article's organization. But along the way, the readability of scientific articles began to decline, as illustrated in the first graphic. For context, those initial Flesch Reading Ease scores [1] are college level; today, those scores are for “professionals” extremely hard to read.

“Whatever positive impact science is supposed to have, it is reduced to the extent that bad writing hampers access.”

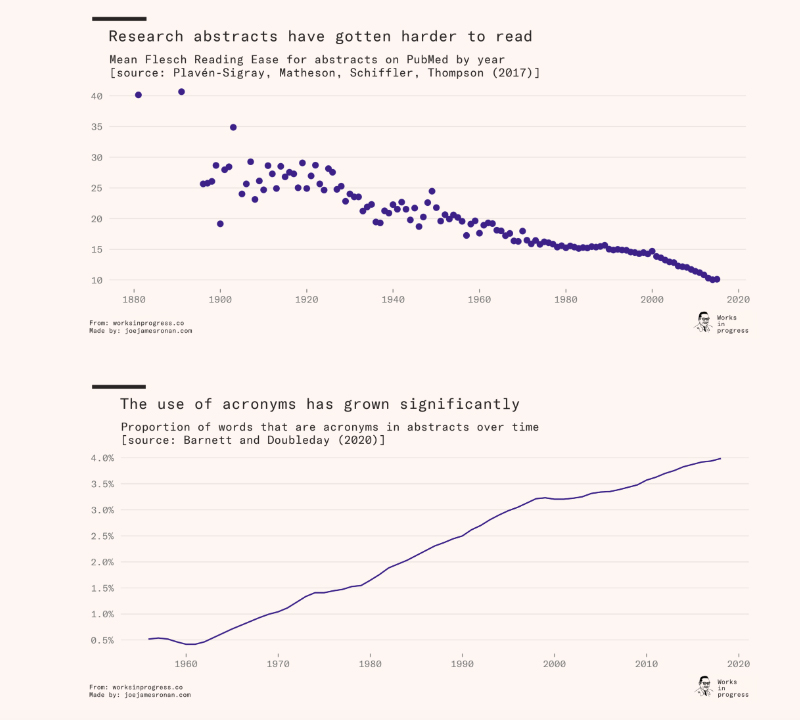

There are several reasons for the decline in readability, among them the use of jargon and acronyms, which you can see has steadily increased. True, we use acronyms too, but mainly for the easily recognizable, e.g., FDA or CDC, and the like. Jargon is far harder to scrub free. That is partly because jargon is how we normally speak to our peers; understanding is implicit. But we can have problems shifting gears when talking to others. I wrote about a similar situation in communicating with patients a while ago.

An unintended consequence of academic job security, tenure, has been the need to “publish or perish,” hopefully in more impactful journals. Of course, those same journals have strict style standards, so writing in today's acceptable impenetrable scientific style is “a safe way that will pass the many filters between their [researchers] work and official recognition. The more contemporary use of pre-prints may open the door to a more accessible writing style, especially as pre-prints and open access expand the education and background of the reading audience.

Finally, as the author writes, “When a document is hard to read, it is also hard to check for mistakes and misinformation.” That seems particularly salient these days when an article's publication is heralded by tweets and articles based more on the abstract than the primary document. If the research itself was more accessible, the shortcut of rewriting the abstract might lessen.

[1] More context, the score for the paragraph you just read is 41, college level. The general level of reading targeted to the average US reader is 8th grade or 60-70, plain English. The reading score is based on the following formula

Reading Score = 206.835 – (1.015 x average sentence length) – (84.6 x average syllables per word)

Source: The Elements of Scientific Style Works in Progress