If you want to read about physicians’ “stigmatizing” terms, you might consider this. But today’s focus is on medical jargon and how it may impede the back and forth between patient and physician. Some forms of jargon are opaque to patients, for example, a “widow maker,” a term describing a very significant narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery that can result in sudden death. (It can also be a widower maker.) Same for acronyms, like npo, or nil per os, translated as nothing by mouth or another way of saying do not eat or drink anything.

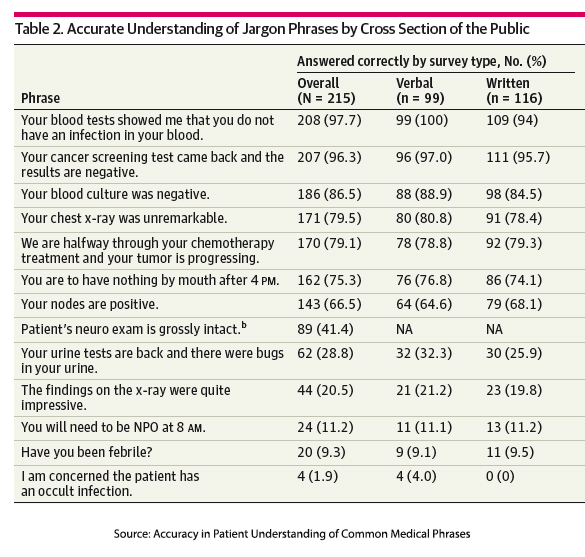

To understand how often jargon interferes with communication, researchers surveyed adults without medical training visiting one of the pavilions at the 2021 Minnesota State Fair. They used a 13-question survey to determine whether typical medical jargon was understood or misunderstood. Despite their hopes for a “cross-sectional” representation, 65% of their 215 participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher (the US average is 34%). Understanding was not affected by the survey being written or given orally, and as the researchers report, the findings were mixed.

You can see the result to the right; the first column has the outcomes to consider for our purposes. What the researchers noted were two distinct types of misunderstandings. There were those related to specific medical jargon, npo, or febrile. These word usages can be easily corrected by simply choosing fewer “jargony” words. When npo was replaced by “having nothing by mouth,” understanding rose from 11% to 75%.

You can see the result to the right; the first column has the outcomes to consider for our purposes. What the researchers noted were two distinct types of misunderstandings. There were those related to specific medical jargon, npo, or febrile. These word usages can be easily corrected by simply choosing fewer “jargony” words. When npo was replaced by “having nothing by mouth,” understanding rose from 11% to 75%.

“More people believed that the phrase “had an occult infection” had something to do with a curse than understood that this meant that they had a hidden infection.”

The second word misunderstanding is a bit more challenging to correct, and it has to do with how common words such as unremarkable, impressive, negative, or positive have very different meanings to those in the trade vs. civilians, the patients. You want an unremarkable chest x-ray because there are no pathologic findings; you do not want your chest x-ray to be impressive because there is something bad there. (By the way, the worst situation for a patient is to be an “interesting case.”) This inversion of word meaning between medical and lay audiences is clearly seen in the use of positive and negative. A negative test is often very good, and a positive one bad.

These “lost in translation” word uses were the most challenging for the patients to understand, and they were among the most accessible word choices for physicians to use in explanations. While the researchers suggested that physicians be more careful in their word choice, that is more of an aspirational goal. The best way, although not a guarantee, of reducing misunderstanding is to bring someone along with you to your medical appointments. Four ears and two brains are much better than two and one. (When I was in practice, most wives insisted on being in the room when I discussed treatment with their husbands; husbands more often chose to go it alone, and I then had to insist on the presence of their spouse.)

When the researchers looked at the demographics of their participants, and remember, these were individuals more highly educated than the average US citizen; they found no demographic of age, gender, or education that protected you from misunderstanding. Prior experience with the medical system did confer some protection, but previous misunderstandings and problems may have gained that protection, so I am not sure relying on experience is not without its risks. Because predictors of misunderstanding are inconsistent, it remains essential to use “clear communication with all patients.”

Source: Accuracy in Patient Understanding of Common Medical Phrases JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.42972