Today's data comes from an online survey of vegans found on Facebook over two months. The vegan diet was assessed using, as always, a food frequency questionnaire. Additional demographic data and the motivation behind choosing a vegan diet were collected, as well as participants' daily physical activity and participation in yoga. There were 516 respondents, all 18 or older. Vegetarians eating eggs or dairy (lacto-ovo-vegetarians) were excluded.

The data from the food frequency questionnaires were “collapsed into 18 food groups” that were characterized in two ways. First, a traditional diet “quality” measure modified from a plant-based diet index. Second, as following a “convenience” or “health-conscious” pattern. Let’s take a moment to unpack these characterizations.

The vegan diet

Vegans have their own food pyramid, which I would share but is copyrighted. [1] A vegan diet requires some nutritional supplementation, particularly vitamin B12, vitamin D, and some iodine – all available as a supplement, iodine-containing algae or enriched sea salt, and outdoor activity to enhance Vitamin D.

While plant-based diets are associated with healthy eating, there is a health-wise hiccup.

“…refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, snacks, and confectionery can be considered “plant-based,” as they or their ingredients are derived from plants, but are to be classified as ultra-processed foods (UPFs).”

Those of you feeding upon the nutritional media's buffet know that just the utterance of the term ultra-processed means the food must be unhealthy. The plant-based UPFs can be found in vegan diets. That is, the group that the researchers characterized as “convenience dietary patterns” – “higher consumption of processed fish and meat alternatives, vegan savory snacks, processed foods, sauces and condiments, cakes and biscuits, sweets and desserts, convenience meals and snacks, fruit juices/smoothies, and refined grains.”

The health-conscious pattern involved “higher consumption of vegetables, fruits, protein alternatives (e.g., tofu), dairy alternatives, potatoes, whole grains, vegetable oils, and fats, and cooking with fresh ingredients and creating own recipes.” More aligned with the popular image of vegans.

A study of 21,000 individuals, including vegetarians and vegans found:

“Higher avoidance of animal-based foods was associated with a higher consumption of UPFs (P < 0.001), with UPFs supplying 33.0%, 32.5%, 37.0%, and 39.5% of energy intakes for meat eaters, pesco-vegetarians, vegetarians, and vegans.”

There it is; vegans ate the greatest percentage of UPFs of all those groups. Now, one more paradoxical finding before moving on. When evaluating the nutritional quality of those diets, that same study found that avoidance of animal-based foods was associated with increasingly healthy diets – the vegans had the highest measures of healthful diets. How is it that they eat the most UPFs and still have the most healthful diet? What exactly is the right proportion?

But I digress. The researchers were interested in identifying the dietary patterns among vegans and their association with physical activity. Here are their findings:

The mean age of participants was 28, overwhelmingly female (85%), and had been vegans for a median of 2.8 years. About 15%, based on BMI, were overweight, another 6% were underweight, and 7% were smokers.

- Among the “health-conscious” vegans, there were more women. They had been vegans longer, and fewer smoked.

- Among the reasons for adopting a vegan diet, the overwhelming majority cited animal welfare (91%), and 60% cited health aspects, consistent with the idea that a vegan diet is more often a moral rather than a health-weighted choice. As might be anticipated, among the “convenience” vegans, animal welfare was an even greater impetus.

- Both groups took supplements, the health-conscious “significantly” more than their convenience brethren.

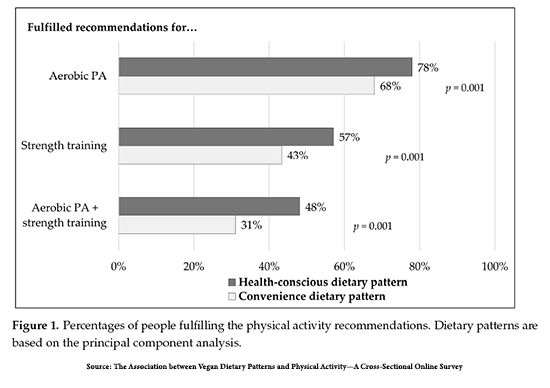

- Seventy-three percent of participants participated weekly in >150 minutes of moderate-vigorous physical activity. Individuals sat for about 6.8 hours daily, but among the health-conscious group, sitting time was an hour per day less. That said, all the vegans were more active than the general population. (For comparison, 44% of the general population participated in that level of physical activity.)

- More health-conscious vegans participated in yoga regularly.

- There was no significant difference in BMI between the two vegan groups. 79% of vegans demonstrated an average weight compared to 47% in the same general population.

“The results consistently showed that higher diet quality, … is associated with a higher PA [physical activity] level.”

“The results consistently showed that higher diet quality, … is associated with a higher PA [physical activity] level.”

Vegans, like the rest of us, are not necessarily more or less healthy based on their diet. Other lifestyle issues are fellow travelers, in this case, physical activity. Leading a healthful life seems to be more than just a diet; it is a mindset. But before ending, let us take down one more dietary myth – in this case, that a vegetarian or vegan diet is too expensive for us to pursue.

In this study, the convenience vegans “had the feeling that they spent more money due to a vegan diet than those in the health-conscious group.” While about a third of participants dined out at “vegan-friendly” restaurants, the convenience group dined out more; it is, after all, convenient. They also purchased more UPFs.

A study paired food demand and commodity prices with different diets across 150 countries. Food prices were higher in higher-income countries, but dietary choices had the most significant effect. In low and lower-middle-income countries, staple crops accounted for the greatest proportion of spending, followed by legumes and nuts, vegetables, and fruits. It was the same pattern in high-income countries, but meat took over the number one spot.

The researchers went on to model the cost of various diets, what they termed dietary patterns:

“In high-income and upper-middle-income countries, all dietary patterns, except for the high-veg pescatarian diets, were less expensive, with greatest cost reductions for the high-grain vegetarian and vegan diets."

[emphasis added]

Food waste accounted globally for nearly 30% of our food expenditures. Reducing food waste can result in additional savings, especially for vegans, more so for grain-based than vegetable-based vegans.

Vegans vary in the reasons for choosing that diet and for how many other aspects of a healthy lifestyle they embrace, just like all of us. Vegans are not a monolithic group; they are a characterization of a population based solely on food choices. But plant-based is not necessarily healthful, by the standards laid down by the food police.

[1] You can find images of the vegan food pyramid here. It is in the top left corner.

Source: The Association between Vegan Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity—A Cross-Sectional Online Survey Nutrients DOI: 10.3390/nu15081847