Dr. Deborah Greenhouse, a pediatrician in South Carolina, tweeted in February,

OK pediatricians, I’m starting a new contest: Who can rack up the highest number of patient calls and texts in one day from parents who can’t find a pharmacy with their child’s #ADHD medication? I’m at 6 so far this morning. Do I win?

That followed a tweet of hers on the same theme last November:

Today: I tried to prescribe amoxicillin for an ear infection: The pharmacy didn’t have it. I tried to prescribe Tamiflu for flu. The pharmacy didn’t have it. I tried to prescribe Adderall for ADHD. The pharmacy didn’t have it. If that doesn’t bother you, it should.

It does bother me. These are important drugs, and such shortages are neither new nor rare. Several years ago, University of Chicago researchers surveyed 719 pharmacists at large and small hospitals across the country and found that all of them reported experiencing at least one drug shortage in the previous year, and 69% had experienced at least 50 shortages in that time. The majority were generic injectable pharmaceuticals commonly used in hospitals, including analgesics, cancer drugs, anesthetics, antipsychotics for psychiatric emergencies, and electrolyte solutions needed for patients on IV supplementation.

The FDA maintains a current list of drugs that are currently in shortage and, as of April 5th, 137 drugs were on it, including the two (amoxicillin and Adderall) mentioned by Dr. Greenhouse. (The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists puts the number at 247.) The FDA's list includes much of the contents of the medicine cabinet of a hospital ICU or emergency room, as well as many drugs used by paramedics.

Adderall. Credit: Tony Webster/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Hospitals, EMTs, and doctors are scrambling to assure adequate supplies of drugs that are in shortage, or to find substitutes for them. In the University of Chicago study, one-third of hospitals had to ration drugs at least once. That means that some patients, like Dr. Greenhouse’s, got the second or third choice of a drug treatment, increasing the likelihood that the drug will be ineffective or only suboptimally effective, or have unwanted side effects.

Especially worrisome is the shortage of about two dozen chemotherapy drugs, the fifth most of any drug category, according to data from the University of Utah Drug Information Service, because, unlike some other categories of drugs, often there aren’t alternatives for chemotherapy drugs. The American Cancer Society warned this month that “first-line treatments for a number of cancers, including triple-negative breast cancer, ovarian cancer and leukemia often experienced by pediatric cancer patients,” are facing shortages that “could lead to delays in treatment that could result in worse outcomes.”

To ameliorate drug shortages, we need a policy change that would enable overseas manufacturers to sell products in the U.S. that already have received marketing approval from certain foreign governments with standards comparable to those of the U.S. FDA, and vice versa. In other words, an approval in one country would be reciprocated automatically by the others (subject to the creation of approved labeling in appropriate format, and other formalities). That would afford drugmakers in those countries rapid access to the U.S. market, helping to alleviate our shortages and preventing future ones.

Reciprocity would ameliorate other problems as well. There have been situations in which FDA has dragged its feet on the approval of important drugs and vaccines. For example, Bexsero, a vaccine to prevent meningitis B, was approved in 2013 by the European Union, Australia and Canada, but not by the FDA until 2015.

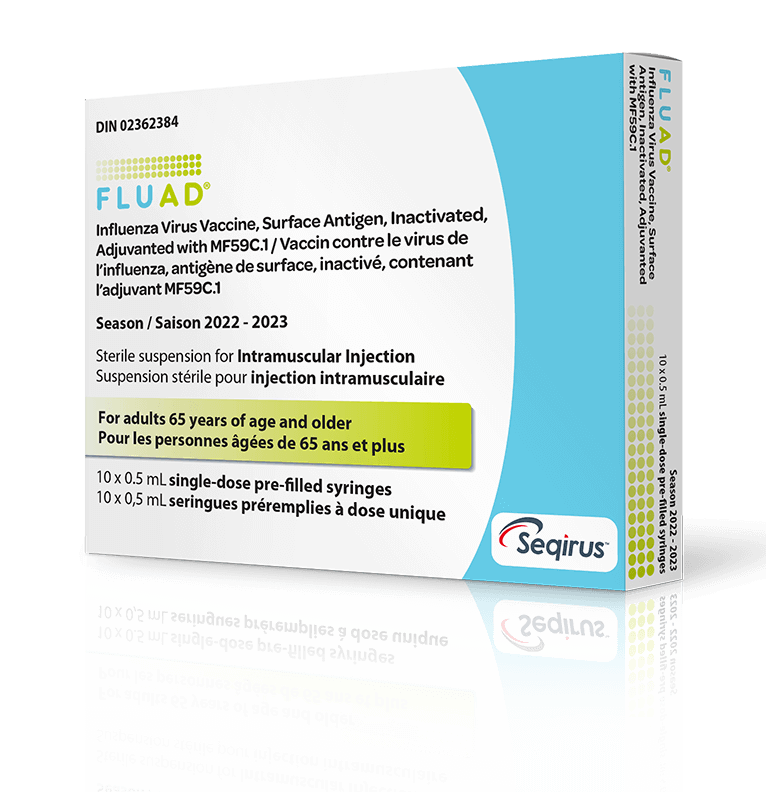

Another example was the long delay before the FDA’s 2015 approval of Fluad, a flu vaccine containing an adjuvant that boosts the immune response. It is used primarily in the elderly, whose immune response to flu vaccines typically is poor. Fluad had been used in Italy since 1997 and approved in more than three dozen countries. The 18‐year delay in availability in the United States undoubtedly resulted in many avoidable hospitalizations and deaths.

Credit: Fluad

There’s another, less obvious problem that reciprocity could help. There have been attempts by senior FDA officials to add a new criterion – superiority to existing therapies – to the statutory requirements of safety and efficacy for the approval of new drugs. Such wandering off the reservation would be neutralized by reciprocity of approvals.

The stage is set for such an advance. The United States has been a leader in the deliberations of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), which have led to harmonized standards among FDA and its foreign counterparts. These countries now have a standardized dossier for seeking approval of new drugs, the U.S. accepts research conducted in other countries to support applications for the approval of new drugs and devices, and the FDA has established Current Good Manufacturing Practices for foreign production facilities. Thus, we’re already part of the way there.

Although reciprocity of regulatory approvals of drugs would be an important advance, it would create some dilemmas. For example, there is the question of what happens to trials underway that were intended to obtain FDA approval if they were preempted by approval in a “reciprocating country?” Would the sponsor terminate them? Similarly, what would happen to a pending New Drug Application that has been submitted to the FDA if a reciprocating country approves the drug? (On average, it takes more than two years for the FDA review.)

Another issue is that the approval by a reciprocating country would constitute a “rebuttable presumption,” a legal principle that presumes something to be true unless proven otherwise, with the burden of proof falling on the party who wishes to rebut or disprove the presumption. Thus, the FDA would need to show cause why the automatic reciprocal approval should not apply; or why, for example, the indications (uses) of the foreign approval are too broad or narrow. If FDA thinks it has evidence to somehow contradict or modify the approval, who would do the arbitration?

Finally, would drug companies stop filing applications for approval in the U.S. entirely, and simply go to regulators in reciprocating countries considered to be “easier” or faster? And if so, would that be good or bad for American consumers?

Americans need to be assured of the availability of pharmaceuticals in the marketplace so that healthcare providers have more reliable inventory, experience fewer shortages, and more choices when shortages arise. Reciprocity of drug regulatory decisions would help to achieve that, and with more drugs on the U.S. market, put downward pressure on prices. The White House and Congress should make make reciprocity of drug approvals a high priority.

Note: Previous versions of this article were published by ACSH and the Genetic Literacy Project.