The number of deaths from COVID-19 is way down from its peak and pandemic-related restrictions and mandates have virtually disappeared, but there are hints we are in for a late summer surge in infections.

Most of us know people, first- or second-hand who have been infected recently. The brother-in-law of a friend of mine attended a baby shower suffering from what he thought were summer allergies…and gave COVID to almost every other attendee. In addition, two distinguished academic physicians known for dispensing advice on COVID recently had serious outcomes from their own bouts with the infection.

In early July, Dr. Bob Wachter, the chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, tweeted about his COVID experience. He had awakened with brain fog and a fever and sweating and took a hot shower, which dropped his blood pressure and caused him to lose consciousness. He later tweeted: “I work (sic) up in a bloody pool on my bathroom floor. There was a dent in the lid of a trashcan, likely where my head had hit. I remembered nothing. As I managed to get up, it was clear that my face was going to need stitches, and more than a couple.”

He had a black eye, a couple of lacerations that required stitches, a subdural hematoma, and a fractured vertebra.

Courtesy of Dr. Bob Wachter

Professor Michael Osterholm, the Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, contracted COVID in March, apparently while “hosting a few (tested) guests for dinner and attending a small, uncrowded music show (wearing an N-95 mask).” He was one of three people infected at the event.

Within several weeks, Dr. Osterholm experienced the onset of long COVID: “By week[s] three and four, the fatigue really set in worse than during the illness itself. And I started having memory loss. If you'd asked me, What's a Champagne and orange juice drink? I couldn't have thought of the word mimosa.”

These accounts are anecdotes, of course, and as the saying goes, in medicine the plural of anecdote is not data. But there are actual data, as well.

The U.S. recorded a 10% increase in new COVID-19 hospital admissions for the week that ended July 15 compared with the previous seven-day period. They are rising fastest in the South, Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states. The percentage of test positivity and Emergency Department visits have also begun to increase:

There are more recent data on test positivity from the Walgreens Covid-19 Index website, which shows the percentage of COVID tests performed at Walgreens locations each week that were positive. Positivity has been trending upward since early April, when the percentage was in the low- to mid-20's. It is 41.6% this week, up 3.4% from last week.

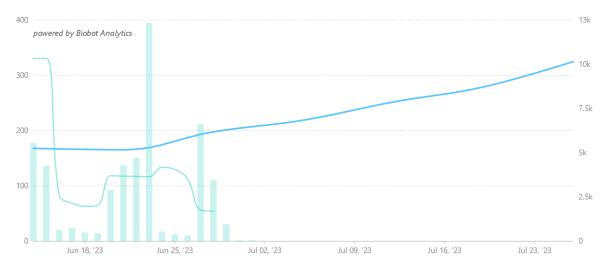

The increases in hospitalizations and test positivity are consistent with upticks in SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in wastewater nationwide. The most pronounced increases are in the South and West:

There's more that's worrisome. The SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to evolve, and there are some new mutants that could be more immune-evasive than its predecessors. For the 2-week period ending August 5, the CDC variant proportions tracker projects that an Omicron subvariant dubbed "Eris," or EG.5, made up 17.3% of cases in the U.S., making it the most common variant for that time period. That's double its proportion a month earlier. And there is preliminary evidence that Eris is more resistant than its predecessors to the humoral immune response -- that is, antibodies -- elicited by infection with previous subvariants.

Reading the tea leaves, University of Texas epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina put it this way last week, "here we are yet again." I agree, especially with schools about to reopen and widespread masking a distant memory.

So, where, exactly, does that leave us?

For one thing, although we don't yet know how transmissible and virulent the new SARS-CoV-2 variants are, we should not underestimate the importance of avoiding COVID infection in the first place. The COVID mortality rate is under one percent, but the incidence of long COVID – the persistence of symptoms or the appearance of new ones following apparent recovery – is much higher.

According to the most recent CDC data, just over 15% of U.S. adults have ever had long COVID, and 5.8% (about 15 million) are suffering from it now (see the figure in this article). As pediatric health researcher Dr. Karen Bonuck wrote recently: “For a condition that's fallen off the radar for those untouched by it, the percentages of U.S. adults reporting any (4.9%) and significant (1.5%) activity limitations is astonishing.” (Emphasis in original.)

Researchers at Imperial College London minced no words in putting long COVID worldwide into perspective: “The oncoming burden of long COVID faced by patients, health-care providers, governments and economies is so large as to be unfathomable…”

Scripps Research's Dr. Eric Topol summed up our current situation accurately:

With all the complacency about COVID, it’s no wonder we keep trailing its progression. We need to get serious about getting the new XBB.1.5 boosters out ASAP, and getting Project NextGen [to develop more-advanced vaccines and new monoclonal antibodies] in high gear. The "pandemic is over" culture is the last thing we need to confront the pressure we’ve put on the virus to find new ways to...find repeat and new hosts and evade our prior immunity.

In addition to the technical advances that Topol referred to, people at high risk for COVID complications, such as the elderly and people with morbidities, should take protective measures. They include being up to date on COVID vaccines, including the new ones that will be released in September or October; wearing a mask in moderate- or high-risk situations; testing if they feel sick; and getting the appropriate medicines quickly if they test positive.