A recent article in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine called attention to the urgent need for research and initiatives to address the syndrome known as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), often called “long COVID.”

The authors, Janko Ž. Nikolich, M.D., Ph.D., and Clifford J. Rosen wrote: “Three years into the COVID pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 is still with us. As the virus evolves, it continues to pose a health threat in terms of both acute infections (or reinfections) and postacute sequelae." And although there have been prodigious efforts to prevent and treat acute infections and reinfections, there is a “void in patient care for [long COVID] that may affect 10% or more of infected people.”

Although most people who get COVID recover within a few days or, at most, weeks, this infection has already killed more than 1.1 million Americans, and the death toll remains in the hundreds per week. In addition, even those with only mild infections can experience long COVID, marked by persistent, sometimes debilitating symptoms that last for months or even years following the acute infection.

According to Scripps Research’s Dr. Eric Topol and coworkers in an article in Nature Reviews Microbiology:

At least 65 million individuals worldwide have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases. The incidence is estimated at 10–30% of non-hospitalized cases, 50–70% of hospitalized patients, and 10–12% of vaccinated cases.

Moreover, the largest number of long COVID cases are in non-hospitalized patients who have experienced a mild acute illness – not because they are more susceptible, but simply because this population represents by far the most overall COVID-19 cases.

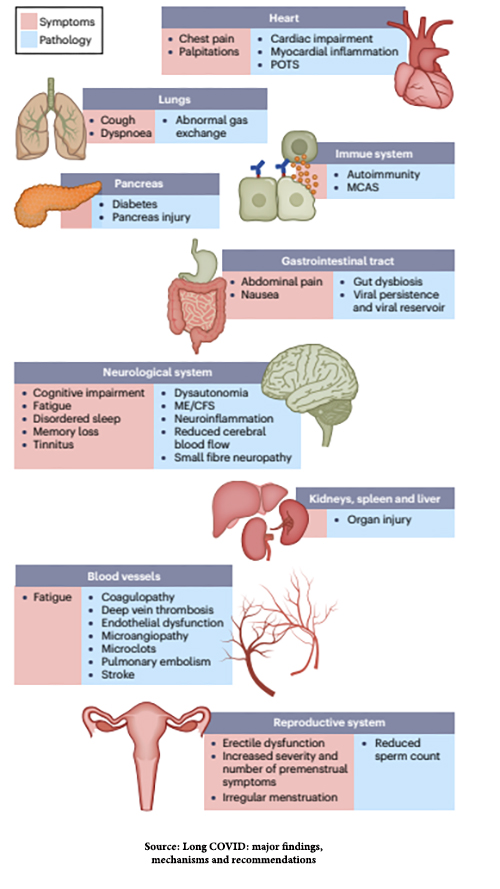

The most common long COVID symptoms and the pathological damage responsible for them are shown in this figure from the Topol et al. article:

This bodes ill for many Americans in the short- and long term. As the number of infections continues to climb, so do cases of long COVID, often causing prolonged pain and suffering so severe that those affected are unable to work; it is thought that there are already perhaps a million such people in the U.S.

That article was published in January, and as many Americans have abandoned COVID precautions and returned to pre-pandemic “normal,” the number of cases of COVID has continued to mount, along with long COVID. The number of Americans who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 is now over 200 million, which translates to at least 20 million people with long COVID, possibly significantly more.

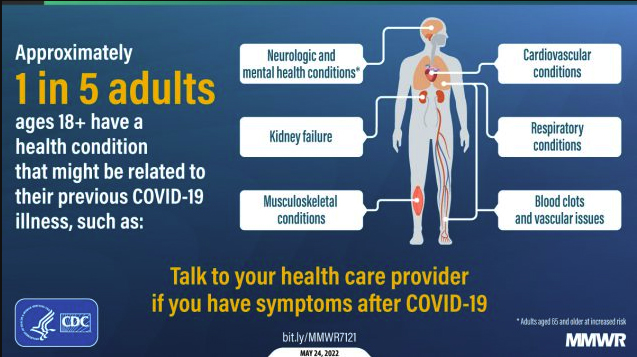

In addition to the persistence of the signs and symptoms following COVID infection shown in the above figure, the CDC has identified the onset of new conditions following infection that "might be related to their previous COVID-19 illness." Think of it as long COVID on steroids. See the figure below.

One problem that long COVID researchers face is that there is no uniform definition of what constitutes the syndrome, so clinicians and affected patients face a maze of difficulties from diagnosis to treatment. Nikolich and Rosen summarized them like this:

The pathophysiology of long COVID remains elusive, in part because of the multiple possible signs, symptoms, and organ systems involved. A lack of understanding of long COVID inevitably also complicates care. Long COVID clinics have been established to provide multidisciplinary care, although most affected patients are also followed by primary care providers or seen by various specialists, depending on the duration and severity of their dominant symptoms. Educational programs for patients and clinicians are lacking. Referrals to subspecialists such as cardiologists, pulmonologists, and neurologists are common but often lead to more delays, fragmentation of care, and frustration at all levels.

Given the lack of good diagnostic or treatment options beyond treating symptoms and the new-onset conditions described above, primary care providers bear much of the brunt of that frustration.

What is to be done to defuse this healthcare time bomb?

Some teaching hospitals have established long COVID clinics staffed with various medical specialists. On the national level, the NIH launched the Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) initiative, which created a network that enrolled adults and children in 33 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. It has three goals: to define the clinical spectrum and pathophysiology of long COVID, to determine its natural history and prevalence, and to characterize the mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 causes long COVID.

Nikolich and Rosen, who are RECOVER researchers, advocate the development of new initiatives to provide ways for clinicians, patients, caregivers, advocacy groups, employers, and government officials to “learn about, adapt, and implement interventions, therapeutics, and other best practices to combat long COVID.”

They believe it should have four components. First, “it should support people with long COVID by coordinating clinical care and rehabilitation, reducing health care disparities, and addressing ongoing and complex medical and psychosocial needs, with a particular focus on patients who currently receive fragmented care or no care at all. Such support could be provided by means of national long COVID centers of excellence.”

Second, there is an urgent need to define, refine, and implement standards of care and best practices. This would be similar to the improvements in the care of acute COVID infections that have occurred during the course of the pandemic.

Third, we must improve how we disseminate and share information to educate clinicians, patients, and communities; broaden access to high-quality care; and reduce demographic disparities.

Fourth, we need training programs for clinicians who care for patients with long COVID. I believe this could begin immediately through the Continuing Medical Education (CME) programs that physicians must enroll in to retain their licensure. (Because long COVID is not relevant to every physician's practice, CME courses on it would not be compulsory.)

The burden of long COVID threatens the U.S. healthcare infrastructure and maybe even the nation’s economy. There is no time to lose in addressing it.