To have a more equal, transparent relationship, physicians have been encouraged to “meet patients where they are,” understand their needs and desires, and share in medical decision-making. We have made our thoughts, laboratory testing, imaging, and procedural documentation freely available through patient “portals” and “Open Notes” programs. All of this is done to make the transaction between provider and consumer more equitable.

It is a charade. Foisted on physicians and patients by academics, patient advocates, and administrators. The intention to fully share in deciding your medical care is important; it just is an elusive goal that letting you read my notes or the radiologist's report does not meet. Why might that be?

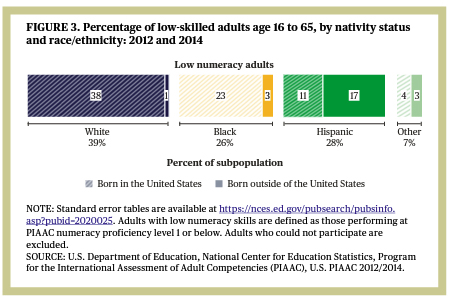

The first hurdle that must be overcome is numeracy – the literacy of handling numbers. Much of laboratory medicine involves ranges and ratios. A third of us lack the basic skills to “make calculations with whole numbers and percentages, estimate numbers or quantity, and interpret simple statistics in text or tables.” Much of this low numeracy can be managed by using pictures to illustrate where a laboratory value lies within a range or by special marking of abnormal values. No class in our public schools teaches us how to manage numbers in the real world unless, of course, you want to calculate the height of a building using its shadow and trigonometry.

The first hurdle that must be overcome is numeracy – the literacy of handling numbers. Much of laboratory medicine involves ranges and ratios. A third of us lack the basic skills to “make calculations with whole numbers and percentages, estimate numbers or quantity, and interpret simple statistics in text or tables.” Much of this low numeracy can be managed by using pictures to illustrate where a laboratory value lies within a range or by special marking of abnormal values. No class in our public schools teaches us how to manage numbers in the real world unless, of course, you want to calculate the height of a building using its shadow and trigonometry.

A related problem with numbers is understanding risk, which is an even more significant problem. This is especially the case when patients, now consumers, are urged to ask a physician their success rate or to seek such information from a public source. What does a 97% success rate mean? Is it better than a 3% rate of failure? In fact, how those numbers are framed makes a difference in our perception. Once again, a graphical representation of risk can help bridge the health literacy gap.

The use of jargon, special words or expressions, our secretive language, make reading our notes and reports more difficult. Like other specialists, physicians use jargon as a professional shorthand to facilitate our work, not obfuscate. By requiring physicians to describe their “encounters” using checkboxes and lists, the electronic medical record has eliminated much of our jargon. The free text entries we are still allowed to write now are scrutinized by the word police. Using the phrase, “the patient was non-compliant,” evidently shifts blame onto the patient. Using the phrase, “the patient did not complete the suggested treatment,” evidently is less hurtful unless, of course, you are considering the clinical outcome, which would be identical.

Some jargon is disguised in a phrase, for example, “the presence of a malignancy cannot be excluded.” That is literally true; you cannot prove an absence. But that phrasing was not placed there for that purpose; it is defensive wording to forestall possible malpractice litigation in the future, shifting responsibility from the physician reading the test to the physician interpreting the findings and communicating them to the patient.

Climbing Everest

There is a wealth of material available to patients to understand their health. There is much explicit knowledge that can be read and learned. But all that book knowledge only prepares you to begin to act on that knowledge. In working, we develop implicit, understood but not easily communicated, practical knowledge. Post-medical school training that lasts 3 to 7 or more years is not because young doctors are “slow” to learn; it is because you need experience as well as book knowledge.

You can find step-by-step guides and video for climbing Mt. Everest. But that is not like the practical knowledge of climbing Everest. Who, in their right mind, would attempt the climb without Sherpas? They are there to do more than carry the load; they provide experience that most of us will never obtain.

The academic belief that physicians and their patients are co-equals in medical decision-making minimizes the value of phronesis, a physician’s practical knowledge. It is attempting to climb Everest without a sherpa. It is why individuals choose urgent care centers over primary care offices – after all, aren’t all Sherpas the same? The advice to climbers applies equally as well to patients,

“Create a rapport with your Sherpa... talk with them all the time and be firm but respectful.”