From Frye to Daubert

From 1923 to 1993, a judge could only admit novel claims if the consensus of the relevant scientific community supported it – the Frye standard. This prevented the introduction of cutting-edge science or emerging critiques by younger researchers, muzzling newcomers who criticized existing dogma.

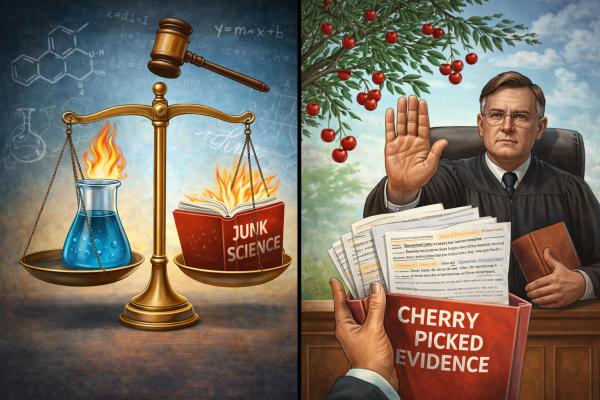

Realizing that Frye chilled the admissibility of cutting-edge science views, in 1970, the Federal Rules of Evidence broadened the standard, allowing all evidence as long as it was based on sound science, and relied on the practice of cross-examination to ferret out uncredible experts. In 1993, the Supreme Court clarified their position in Daubert v. Merrell Dow, now adopted in all federal courts and all but six states. Daubert and subsequent cases refined the standards for distinguishing between sound and junk science even further. (It must be noted that lawyers’ name-calling established science as junk doesn’t necessarily make it so and often serves as a public relations tactic.)

The Daubert standard does not give carte blanche to any new theory, nor to all novel claims. It sets forth theoretical parameters that must be satisfied before a jury can consider the evidence: reliability, relevance, and “the fit” of the evidence and the research to the facts of the case, implicitly requiring compliance with the scientific method in the research relied on. It also imposes on the judge the role of gatekeeper – policing problematic or pseudo-science. Later cases expanded Daubert and required any expert opinion to be tethered to the methodology and the research, disallowing experts from pontificating or opining purely on personal assessment. The focus on Daubert was on the scientific soundness of the methodology; the Joiner case expanded the focus to the legitimacy of the expert’s conclusion.

Scientific reliability is usually measured by statistical significance; the validity or relevance standard may be satisfied if the research is performed in conformity with the methodological norms of the particular field, yielding objective results. Daubert suggests additional, optional tests judges may use to evaluate claims:

- Whether the underlying research was peer-reviewed and published.

- Whether the theory was tested via experiment and yielded objective results.

- Whether an acceptable error rate was calculated.

- Consideration of the Frye index of acceptance, scientific consensus.

In 1993, when Daubert was decided, there were far fewer medical journals, and most were published by independent, reputable houses that relied on impeccable experts to review. Today, the number of journals has mushroomed, along with fraudulent research (some of which is later retracted), and many articles and journals are financed by organizations supporting the claims being litigated. This has weakened the Daubert standard, although there are some practical remedies.

- Identify retracted studies, for example, through databases, like Retraction Watch

- Identify the financial and ideological conflicts of interest of both the publisher and the author

- Investigate the Impact Factor, a measure of a journal’s impact, on the scientific community

- Assess the editorial board's prestige and partisan ties to industry or ideological groups

Following its overarching decision on the role of a judge in evaluating scientific evidence, the Supreme Court sent the Daubert case back to the 9th Circuit to implement its rulings in the context of the facts of the case (Does Bendectin, an anti-nausea drug, cause birth defects if ingested during pregnancy?) The latter opinion provides yet additional considerations for judicial assessment, noting :

“expert opinion based on a methodology that diverges "significantly from the procedures accepted by recognized authorities in the field ... Are not 'generally accepted as a reliable technique.’” [emphasis added]

Of major concern to the court is the independence of the expert’s research:

“ testimony proffered by an expert … based directly on legitimate, preexisting research unrelated to the litigation provides the most persuasive basis for concluding that the opinions he expresses were "derived by the scientific method. … Experts who have developed their opinions expressly for purposes of testifying are not favored under Daubert…. Independent research carries its own indicia of reliability, ….” [emphasis added]

When evaluating the value of even a noted expert, it is worth noting when their first research on the subject was published - before or after being retained by either side of the controversy?

The Cherry-Picker

Another bug-a-boo of gatekeepers is “the Chinese Menu” philosophy (called cherry-picking, by the courts)- when experts rely solely on cases supporting their position, discounting those that don’t, without explaining any reasonable and consistent basis or methodology for this approach, i.e., poor study design or small number of subjects.

Numerous judges have rejected the cherry-picking expert, including in the NY Acetaminophen-Autism cases and the federal and Delaware Zantac cases. Although this decision reflects judicial discretion, it is rarely disturbed on appeal; however, several of these are currently on appeal, and we will soon learn the validity of judicial rejection on this ground.

Another clue of judicial disfavor occurs when courts reject reanalysis of epidemiological studies that had neither been published nor subjected to peer review, finding unpublished reanalysis "particularly problematic in light of the massive weight of the original published studies… all of which had undergone full scrutiny from the scientific community."

But what happens if there is research both in favor of and opposing an expert’s position? After judicial determination that all proffered scientific evidence is sound, i.e., reliable, relevant, and fit, it is submitted for jury consideration, and less significant infirmities, including witness credibility, are intended to be exposed via cross-examination.

Games People Play: The Publication Version

Publication still plays a significant role in presenting an expert’s views as authoritative.

Generally speaking, reputable journals, as well as pre-peer-reviewed publication sites, like the Social Science Research Network, require a declaration of conflict of interest, financial or ideological, and these can be used to assess the impartiality of the editors and authors.

Another “look good” tactic used by unreliable groups or authors cites various articles that appear impressive but, on review, do not sustain the underlying premise. That means it’s critical to check the researchers’ cited literature, much as courts check the underlying cases relied on to support legal arguments. In the age of AI, where hallucinated sources are not uncommon, this practice becomes mandatory. Another tactic is to cite a purported article in a mainstream publication, only to learn that it is nothing more than a Letter to the Editor, which generally are not peer-reviewed, are often composed by industrial or ideological advocates, and sometimes involve official associations and financial conflicts of interest.

While these partisan pieces may be exposed during cross-examination during litigation, it is up to you, dear reader, to read the primary study and check its citations if issues arise before litigation ensues.

While even reputable publications, such as The Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, have published articles that turned out to be erroneous (and must be verified by replicated research), valid research and information on the internet is being pulled by the government when the outcome may conflict with a political position, depriving readers of valid alternative research. The antidote isn’t clear.

At the end of judicial analysis comes the question, who is objecting, and what interests do they have in the outcome? The same analysis should apply to critiques of position papers in journals or internet publications like ours. Who wrote the critique, and what do they have to gain?