Much digital ink has been generated praising and condemning the long-awaited MAHA-driven dietary guidance. STAT reported on the conflicting interests involved in the report. Dr. Makary, the FDA Commissioner, and his Deputy Commissioner for Human Food, Kyle Diamantas, have provided the rationale for the new guidelines in The Free Press

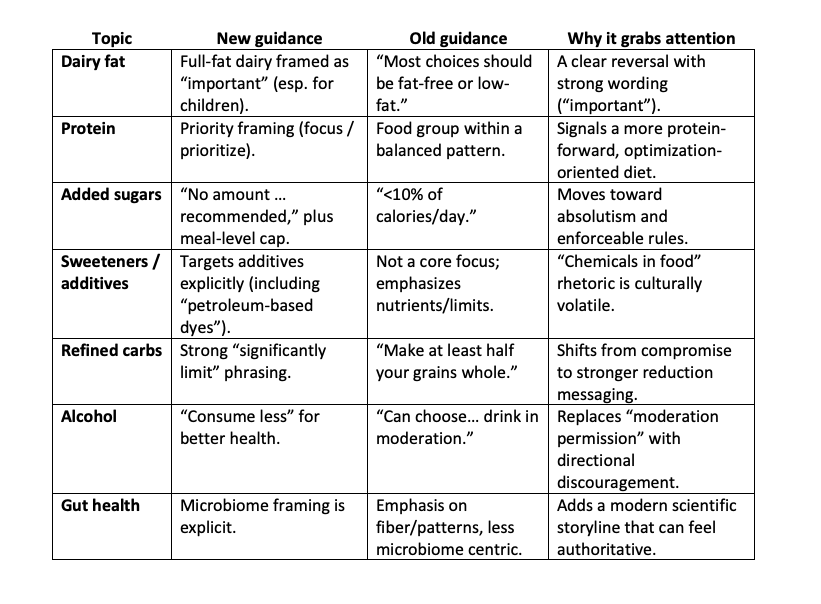

You can find a copy of the new dietary guidance here, and the old guidance here. Before turning to interpretation, it is useful to briefly summarize the most notable substantive changes.

From Nutrient Targets to Food Judgments

- Full-fat dairy is no longer a “guilty pleasure.” – Perhaps the most striking shift, the old guidelines consistently steered people toward fat-free or low-fat dairy. The new guidance instead permits full-fat dairy, with the caveat that it contain no added sugars.

- Protein becomes a centerpiece – The new guidance puts protein at the center of the plate. It encourages prioritizing protein foods throughout the day and frames “protein foods” as a central anchor of a healthy diet, often paired with messaging about minimizing industrial processing, starch fillers, and additives. The old guidance treated protein as one of several food groups within a balanced pattern

- Animal fats get a partial reprieve – The new guidance adopts a more permissive tone toward traditional animal fats such as butter and tallow, treating them as acceptable within a whole-food pattern. At the same time, it retains the long-standing saturated fat cap of less than 10% of calories, preserving an underlying tension between permission and restraint.

- Added sugar moves toward “zero tolerance” – While the old guidance set a numeric ceiling, the new document goes further, stating that no amount of added sugar is recommended and introducing per-meal thresholds—an unmistakably stronger signal.

- The guidelines broaden from nutrients to ingredients – The old guidance is overwhelmingly nutrient-focused—added sugars, saturated fat, sodium, calories. The new guidelines explicitly target categories of additives and modern food engineering, including artificial flavors, petroleum-based dyes, artificial preservatives, and low-calorie non-nutritive sweeteners.

- Refined carbohydrates get a sharper warning – The new guidelines use much stronger, reduction-oriented language and explicitly call for significantly limiting refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed snack foods.

- Alcohol becomes less about “moderation” – Where the old guidance emphasized choice through numeric thresholds, the new guidelines compress this into a more directional discouragement: “Consume less alcohol for better overall health.”

- Gut health and the microbiome go mainstream – The new guidelines explicitly frame diet through the gut microbiome lens, asserting that highly processed foods can disrupt balance while fiber-rich and fermented foods support diversity.

The New Food Fight Is Linguistic

Despite these changes, few Americans closely follow U.S. dietary guidelines. One study found that only about a third of respondents were aware of MyPlate, and among them, only 10% had tried to follow the advice. In practice, people rarely organize their eating around official guidance, constrained instead by cost, culture, habit, and time scarcity.

This gap between official recommendations and lived reality helps explain why the language of the guidelines—not just their content—matters.

The Guidelines Don’t Just Advise—They Judge

A Liberal Governance Register

The old guidelines’ rhetoric is largely administrative and population-oriented: “healthy dietary patterns,” “nutrient-dense,” “within calorie limits,”. It repeatedly signals choice within a framework (“can choose…”), and it’s written in a way that can be translated without sounding emotionally charged. The old guidance sets limits, provides options, nudge patterns, and lets individuals choose.

A Moral-Public-Health Register

By contrast, the new guidelines adopt a markedly different rhetorical register across categories:

- Absolutes and high-certainty language (“no amount… recommended,” “significantly limit”) that leaves little room for compromise.

Assertive imperative verbs (“avoid,” “focus on”) and priority framing—such as protein appearing in “every meal”—that drift from guidance toward instruction.

Morally coded industrial language (“petroleum-based dyes,” “highly processed”) that identifies villains and evokes contamination and disgust, aligning with broader narratives of industrial distrust, regulatory capture, and bodily autonomy.

Quantification and specificity convey a sense of scientific certainty even where evidence remains mixed, particularly in discussions of the microbiome.

The new guidelines read like an advocacy-forward health manifesto. Its language is more behavioral, prescriptive, and moralized with heightened focus on purity (whole foods) versus contamination (processed foods, additives, “petroleum-based dyes”). It makes the message feel more apparent and more urgent. However, because it speaks in more categorical terms, i.e., “no safe level,” it becomes more like a mandate. The new guidance identifies villains (processed foods/additives), elevates preferred behaviors (protein, water), and frames “good choices” as obvious. This can be received as both empowering autonomy (“choose real food; reject industry”) or as soft coercion (“do this or you’re doing it wrong”), depending upon your nutri-political leanings.

Purity, Villains, and “Medical Freedom”

Read side by side, the old and new guidelines do not merely recommend different dietary behaviors; they speak in fundamentally different rhetorical tones.What emerges, then, is not just a policy update but a shift in how authority, responsibility, and health itself are communicated.

The old Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA 2020–2025) largely adopt the language of governance, emphasizing autonomy as part of its public-facing stance, stating that adults “can choose not to drink, or to drink in moderation,” and explicitly noting that “individuals ultimately decide what and how much to consume.”

The new guidelines, by contrast, read as a behavioral call to action. Imperative verbs and ranking language give the document the feel of an ethical clarity statement, a shift that is especially visible in how industrial food inputs are described. Rather than focusing solely on nutrients, the new document names industrial “bad actors” in emotive terms—“artificial flavors,” “artificial preservatives,” and, most strikingly, “petroleum-based dyes.”

Perhaps the most consequential rhetorical shift is the document’s repeated use of positive-necessity language—phrasing that not merely recommends but implies what responsible self-care, parenting, and citizenship look like.

The old DGA is explicitly designed for broad implementation across “government, communities, organizations, businesses, and individuals,” and is deeply intertwined with federal nutrition programs. This administrative reach makes it an easy target for those suspicious of centralized authority, even as it enables nationwide consistency.

The new document, by contrast, is rhetorically positioned to resonate with audiences who value personal autonomy in opposition to “industrial” encroachment. Its language can be read as pro-freedom—from additives, ultra-processed foods, and the engineered hyperpalatability of sugar. Yet the same rhetorical tools that increase clarity and urgency—absolutist statements, “avoid” language, villain-hero framing—also increase the sense that the guidelines are policy-ready mandates rather than flexible recommendations.

The key point is not that one rhetorical style is more “scientific” than the other. Rather, the old guidelines speak in the voice of administrative public health, while the new guidelines adopt the language of moralized consumer health advocacy. The activist-style labeling of the new guidance contrasts with the old document’s regulatory neutrality, which can, in turn, feel paternalistic. This shift reshapes how recommendations are perceived, and how readily they become ammunition in the recurring conflict between public-health norms and claims of “medical freedom.”