End-of-life care is an uncomfortable topic for many if not all of us. Many individuals express a preference for dying in their own homes, providing a sense of control, privacy, and the ability to be surrounded by family and friends. Home hospice care allows for the provision of more skilled care in the home. For others, the nature of their illness, the need for medical interventions, or the lack of adequate support for home-based care means they end their lives in institutions, nursing homes, or inpatient care.

The study in BMC Geriatrics looked at a 10% cohort of all Medicare beneficiaries dying in 2018, where and how their care changed during the last three years of their life. There were three clusters of care:

- 59% of Medicare beneficiaries remained at home, utilizing some skilled home or institutional care in their final few months.

- 27% made use of skilled home care and hospice for the entire period.

- 14% spent those years in nursing homes and with inpatient care.

The researchers also calculated the time beneficiaries spend in these clusters receiving more intense care, which they describe as trajectories. Here are those findings visualized.

- For those simply remaining at home, more intense care, either at home or in the hospital, was necessary during those last 3 months.

- For those already receiving more skilled home care, intensified care was again needed in those remaining few months, but the use of intensified skilled home care greatly outweighed hospitalization.

- The need for hospitalization was significantly greater for those receiving care in nursing homes and began much earlier in those remaining three years.

From the vantage point of a physician, any opportunity to keep a patient in their home with appropriate care and support is a win for the patient and their family and its cost to the healthcare ecology. While the data used by the researchers did not quantify or describe support available from family or friends, the demographic data on those clusters does provide some insight and perhaps a guide to what we can do.

More women than men received skilled home or institutionalized care. Several factors might account for this. We can begin with the stereotypical idea that women are more often caregivers than men. According to the Family Caregiver Alliance,

- Upwards of 75% of all caregivers are female and may spend as much as 50% more time providing care than males.

- 36% of female caregivers handle the most difficult caregiving tasks (i.e., bathing, toileting, and dressing) compared with 24% of their male counterparts, who are more likely to help with finances, arrangement of care, and other less burdensome tasks.

As a result, more men can be cared for at home or with skilled assistance. Women tend to outlive men by about 4.5 years, so wives are less likely to have a husband to help out. Finally, women suffer from Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias at greater rates than men, roughly at twice the rate. Dementia, because of a multitude of behavior issues, is one of the clinical conditions associated with the greater use of skilled home care and institutional care.

Individuals requiring more complex care frequently need skilled care at home or in nursing homes. At its simplest, there is a higher percentage of beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions in the skilled home care and institutional clusters. A closer look at the data suggests that some conditions, in addition to dementia, e.g., depression and stroke, may require more care than can be easily provided, even in a supportive home.

Beneficiaries eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid (dual-eligible) were more likely to receive extended institutional care. Dual-eligibility is based upon income, and often the medical conditions and disabilities that led to the dual-eligibility status are such that significant skilled care is necessary, making home care difficult.

Location, location, location - and law

As with many healthcare disparities, location can often play a significant role. Living in a disadvantaged area or a rural area was associated with more end-of-life care in nursing homes and hospitals. While not directly studied, it is certainly possible that both locations cannot provide adequate support. Social isolation involves an objective lack of social contact and connections, often conflated with loneliness, which is the subjective feeling of social isolation. Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood is associated with about a 30% increase in loneliness, suggesting the lack of family and friend support networks. Rural areas may have more or less of these necessary social networks, but significant distances can often separate them. Rural areas may also have fewer available social services. The combination of greater geographic separation and fewer resources may be another reason why those in non-metropolitan areas are more likely to receive end-of-life care in institutions.

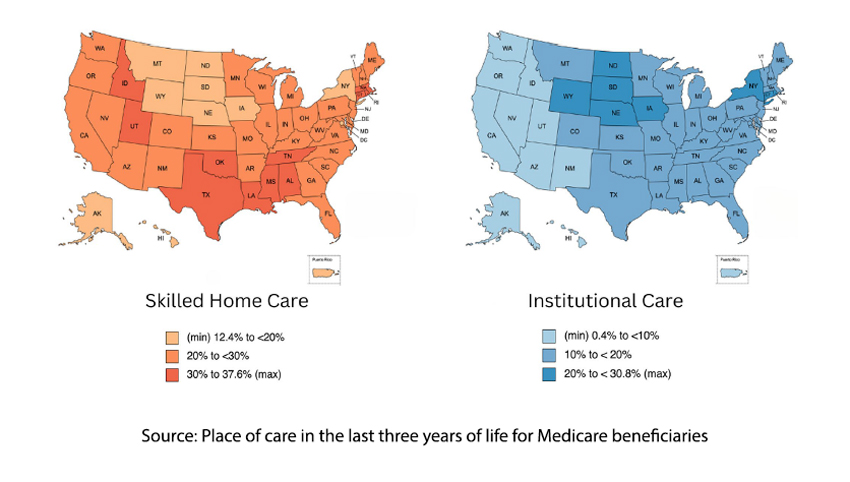

Finally, the policies enacted at the state level can influence where we spend our final days.

Finally, the policies enacted at the state level can influence where we spend our final days.

Skilled home care was more prevalent in our southern States, and institutional care more prevalent in the Midwest. In general, States with more generous home health care and hospice benefits had higher rates of skilled home care; those with more restrictive policies on nursing home care had higher rates of institutional care.

Source: Place of care in the last three years of life for Medicare beneficiaries BMC Geriatrics DOI: 10.1186/s12877-023-04610-w