Systems thrive when environments are structured for success, whether in a Michelin-starred kitchen or a termite colony. Public health is no different: the environment must reinforce the message, and adaptation must be framed as strength rather than weakness. That is the test facing the new Making America Healthy Again (MAHA) initiative: will it structure an environment that nudges us toward health, or rely on slogans that leave individuals struggling on their own? MAHA’s rhetoric of personal responsibility risks ignoring these truths, leaving its vision more symbolic than substantive. If MAHA’s plan prioritizes symbolism over substance, its legacy will be a missed opportunity at best—and a squandered moment of national need at worst.

In the next few weeks, the MAHA Commission will release its plan to help us, especially children, become healthy again. Set against a backdrop of a movement fueled by demands for change but led by those who eschew governmental regulation replacing “personal” responsibility, and a public widely divided over the public health response to COVID, it is worthwhile to ask how public health campaigns work, and how they might succeed or fail in our latest crisis.

To answer that, I turn to three concepts—kaizen, mise en place, and stigmergy—that together highlight how environments, not just individuals, shape health outcomes. Let’s dig in.

Step by Step: Kaizen and Incremental Change

Born in post-war Japan, kaizen is a philosophy describing “continuous improvement,” made famous by the Toyota Production System. Like compound interest’s impact on savings, it champions small, incremental changes that, over time, compound into substantial gains. It is an endless cycle of observation, making a problem visible, then refining and implementing solutions in small, manageable steps, embedding change into our daily private or public lives. While incremental in its actions, it is sweeping in its effect. But improvement alone isn’t sufficient; you require preparation. That’s where mise en place enters.

Mise en Place and Preparation

As many foodies know, the French term “mise en place,” meaning “everything in its place,” originates from professional kitchens. It means preparing and arranging your workstation and work so that every ingredient and tool is in the right place, available at the right time. Nothing interrupts the flow, where the individual is completely immersed and absorbed, where the boundary between the individual and the activity dissolves, leaving our actions and experience effortless. However, even though preparation is necessary it is not sufficient. Just as “yes, chef” acts as acknowledgment in the kitchen, coordination among many requires signals embedded in the environment itself, the work of stigmergy.

Let the Environment Speak: Stigmergy and Social Cues

A new word for me, perhaps for you too, stigmergy comes from a mashup of biology and complexity science. It was coined by the entomologist Pierre-Paul Grassé, describing how social insects, in this case termites, but equally applicable to ants and bees, build their homes and societies without centralized planning. Stigmergy describes how coordination can be achieved indirectly through environmental cues, where the traces we leave prompt responses in others.

Taken together, these three concepts reveal a shared principle: structure shapes success, forming a blueprint that can make or break public health efforts like MAHA.

Three Principles, One Public Health Blueprint

There is a tension underlying all public health measures, the balancing of individual autonomy with societal obligation. All three of these principles restructure our environment so that we, as social creatures, act more effectively and with less confusion. From the viewpoint of public health,

- Mise en place: Provide a solid foundation, the right materials, the right place, and the right time.

- Kaizen: Continuously improves the method and the message using feedback.

- Stigmergy: Creating an environment that itself reinforces and spreads the message.

Together, they can guide us towards public health initiatives that are well-prepared, continually improving, and reinforced through our lived environment, steering a middle path between autonomy and public good that now frames the discussion of MAHA’s plans. We’ve seen this play out before, in the long battle over tobacco

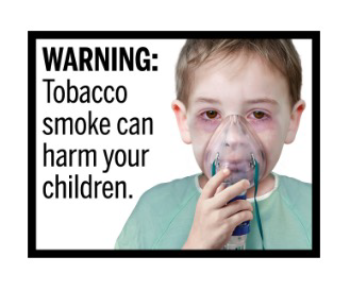

Tobacco: The Blueprint’s Slow Test

Kaizen was present throughout our evolving relationship with tobacco. From the quiet observation that cigarettes might result in weight loss, making it a selling point for weight-conscious women, to the long-delayed realization that smoking accelerates our dying. Observation led to new methods and messages, from Virginia Slim ads to warning labels, from physicians endorsing cigarette smoking to the Surgeon General’s report. Kaizen’s incrementalism has brought us from a population where 50% of young men and 30% of young women smoked to today, where that percentage hovers closer to 10-15%. Mise en Place played its role, moving cigarettes behind the counter, and every pack coming with a message. Stigmaery made cigarette packs environmental cues, with their graphic warnings and taxation, rising to nearly 50% per pack in New York. If tobacco was the slow-burning test of these principles, COVID was the stress test.

Kaizen was present throughout our evolving relationship with tobacco. From the quiet observation that cigarettes might result in weight loss, making it a selling point for weight-conscious women, to the long-delayed realization that smoking accelerates our dying. Observation led to new methods and messages, from Virginia Slim ads to warning labels, from physicians endorsing cigarette smoking to the Surgeon General’s report. Kaizen’s incrementalism has brought us from a population where 50% of young men and 30% of young women smoked to today, where that percentage hovers closer to 10-15%. Mise en Place played its role, moving cigarettes behind the counter, and every pack coming with a message. Stigmaery made cigarette packs environmental cues, with their graphic warnings and taxation, rising to nearly 50% per pack in New York. If tobacco was the slow-burning test of these principles, COVID was the stress test.

COVID: The Stress Test of Public Health

COVID showed how fragile our blueprint can be when stress-tested at speed. The virus didn’t wait for perfect preparation; public health systems had to adapt on the fly. Its lessons were blunt…

- A lack of mise en place Many nations lacked ready supplies of masks, ventilators, or testing kits. In many cases, guidance arrived late or in conflicting, confusing formats. Early messaging was reactive, and the virus’s spread outran our communications efforts. Once resources arrived, pop-up testing and vaccine sites followed mise en place principles, with more consistent diagnostic and treatment flows.

- Stigmergy’s Mixed Environmental Signals Floor stickers, plexiglass barriers, and sanitizer stations silently communicated the “new rules.” Empty stadiums and taped-off playgrounds became unmistakable reminders of the crisis. Masks created visible cues, but their inconsistent application, with masking norms varying wildly, resulted in a contested, confusing visual landscape. We fractionated into many stigmergic “hives,” consistent locally, inconsistent regionally, and nationally.

- Kaizen’s Strained Feedback Loop Scientific understanding evolved rapidly, resulting in shifting guidance; after all, as evidence changes, so should behavior. Variant-specific boosters reflected Kaizen thinking: adjusting tools to meet evolving threats. However, rapid changes without clear explanation were seen as inconsistent rather than evidence-based adaptation. “The science has changed” sounded to many as “We were wrong,” eroding trust.

COVID’s take-home lessons reflect the need for continuous mise en place preparedness. For our built and cultural environment to be uniform, while paradoxically tailored to local needs and concerns, stigmergy’s cues only work when consistently applied; conflicting signals create confusion and reduce compliance. Most critically, kaizen needs transparent storytelling so that adaptation is framed as intentional and evidence-driven; clear explanations maintain trust even when guidance changes.

What MAHA Must Learn—or Risk Irrelevance

From kitchens to termite mounds, success stems from environments that facilitate right action, and the interplay of kaizen, mise en place, and stigmergy can make or break these efforts. The science of saving lives isn’t just about having the right facts—it’s about preparing the stage, letting the environment speak, and adapting without losing the audience.

So far, the MAHA warriors have demonstrated kaizen. Still, their stress on the autonomy of individuals over the collective needs of the herd put the implementations afforded by mise en place and stigmergy at risk. The earliest “leaked” trial balloons of the MAHA Commission appear to reflect a will to implement nothing other than the low-hanging cosmetic fruit, like food coloring and perhaps some forms of sugar or oil, or the ever-popular “need for more study.”

The real test of MAHA will not be in the speeches, hashtags, or focus-grouped slogans. It will be in whether the Commission can prepare the ground, adapt transparently, and weave health into the environment so seamlessly that good choices feel natural rather than imposed. Fail at those, and MAHA will be remembered as yet another march of well-intentioned rhetoric into the valley of irrelevance.