It's almost impossible to go for a week without the rare earth elements popping up in the news. A few recent examples:

- U.S. agency wants to buy scandium oxide from Rio Tinto for defense stockpile — September 22, 2025

Reuters - G7 weighs price floors for rare earths to counter China’s dominance — September 24, 2025

Reuters - U.S. magnet start-up targets China’s grip on rare earths — September 23, 2025

Financial Times - China tightens grip over rare earth supply quotas — August 22, 2025

Reuters

What Are Rare Earths?

You are entirely forgiven for not knowing this, since they are not especially rare — cerium is about as common as copper. The problem is that they’re difficult to isolate and purify; it wouldn’t be entirely inappropriate to call them the “Pain-in-the-Ass Earths.”

Annoying or not, these metals are essential in modern life. They make electric cars go, wind turbines spin, and smartphones smarter. They’re in magnets, batteries, and guidance systems. In short, they are the invisible backbone of high-performance technology.

The Chemistry of the Rare Earths

You know what that means, right? Yes — it’s the often-requested (but seldom enjoyed) Dreaded Chemistry Lesson From Hell® with your beloved hosts Steve and Irving!

Only now, the boys have taken a sabbatical from one kind of hell to another: the adjunct lecturer circuit, where they get paid peanuts to teach Chem 101 to a bunch of disinterested 18-year-old TikTok wannabe influencers in Sandusky, Ohio.

Steve (Left) and Irving take a turn in academia. This does not make them happy. As if anything does.

Steve and Irving Spring a Pop Quiz!

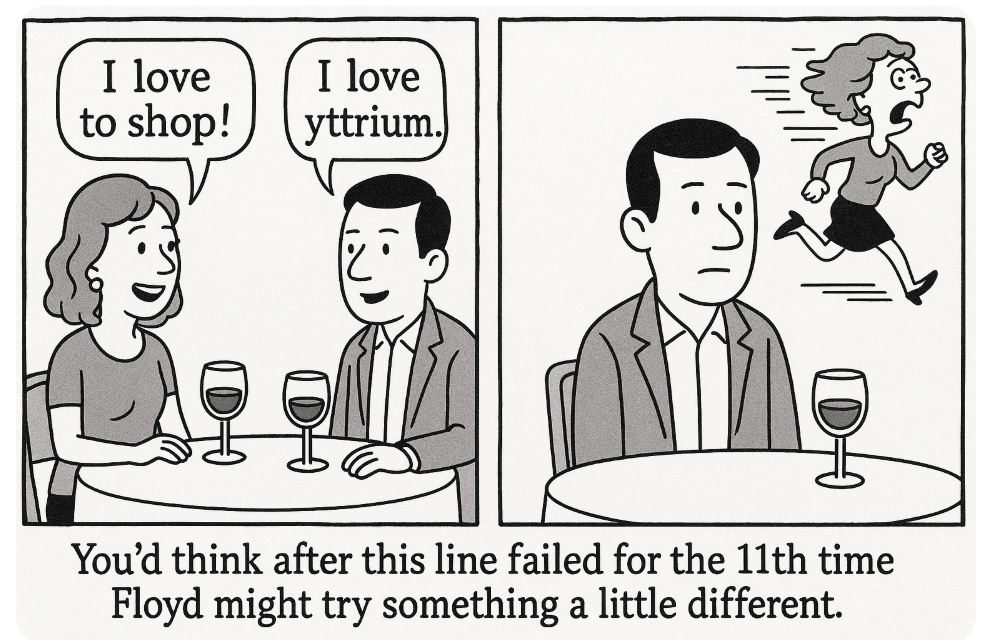

There are only 14 elements in the periodic table with a single-letter symbol. Name them all.

At best, you’ll get 13: B, C, F, H, I, K, N, O, P, S, U, V, W.

And you’ll be forgiven if you didn’t come up with Y: yttrium. And why would you? It’s not exactly a common topic of conversation, especially in the world of online dating, where it fails miserably.

So, Why Should Anyone Care?

Because yttrium and its exotic-sounding cousins are important enough to fight over.

This fall, European manufacturers had a small panic attack when China tightened export rules on rare earth elements. Prices for neodymium and praseodymium — two VIPs of the magnet world — shot up nearly 40% in weeks. Washington, Brussels, and New Delhi all vowed action, as if announcing a task force makes chemistry easier. Meanwhile, researchers in Zurich and Toronto are quietly trying to pull rare earths out of yesterday’s junk laptops.

Yttrium metal. Zzzzz. Photo: Flickr

The drama raises an obvious question: if these metals are everywhere in the Earth’s crust, why are they such a pain in the ass to get?

Pure Rare Earths are Rare Indeed

Rare earths comprise a family of 17 metals: scandium, yttrium, and a block of 15 elements called the lanthanides. [1]They live together in a row at the bottom of the periodic table, all with nearly identical chemistry, which is why they get lumped together as a group, and why they’re so hard to separate.

On paper, they’re not rare at all. Cerium is about as common as copper. So is Ytterbium, a long-time favorite in the Scrabble world.

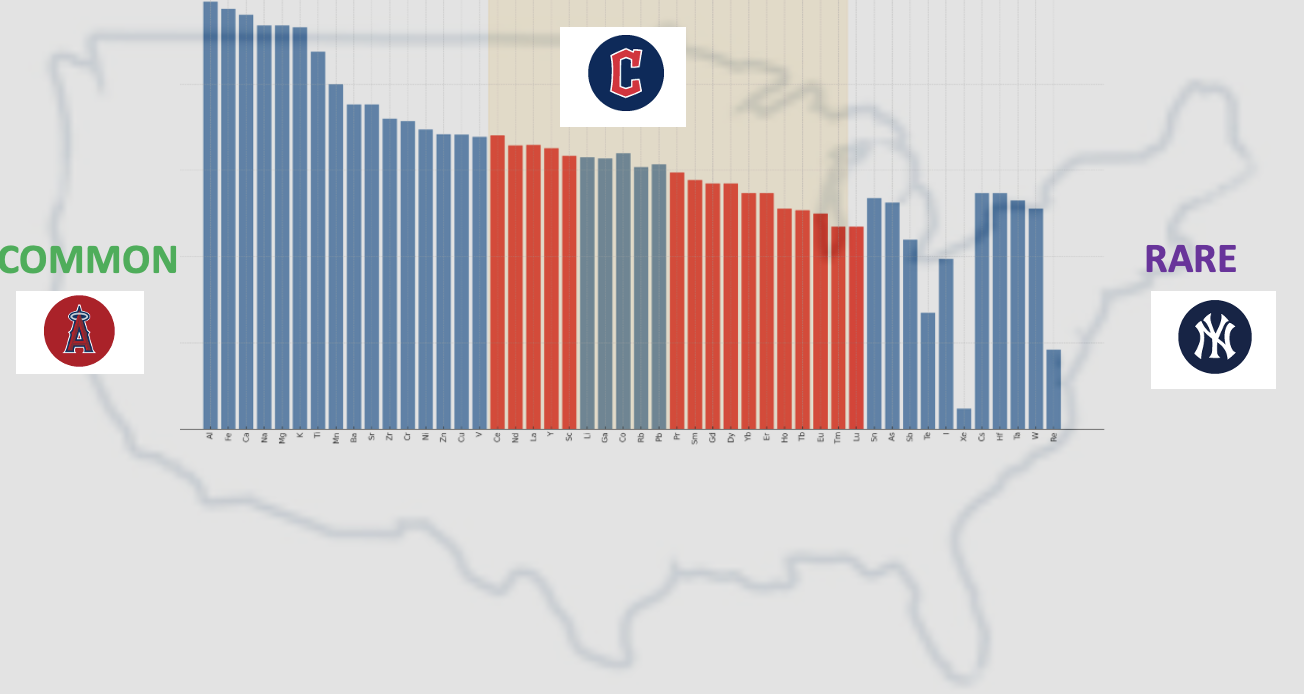

Look where they sit compared to other metals in terms of abundance. Rare earths are neither abundant nor rare. They huddle together in the middle — the Midwest of the periodic table.

Figure 1. A graph displaying about one-third of the metals in the periodic table. The most common, Al, Fe, and Ca... are found in the American League West, while the rarest ones, In, Os, Rh, are in the American League East. Shown are the 40 in the middle. Note how the lanthanides are grouped together in the AL Central. The height of the bars is a (very) rough measure of relative abundance.

Why Are They So Difficult to Get?

Here’s the problem: chemically, they all behave almost exactly the same. Most sit happily in the +3 oxidation state. The only difference is that, as you move across the series, the ions shrink only slightly — the infamous lanthanide contraction. That means their properties are nearly identical.

By contrast, metals with +1 or +2 oxidation states (e.g., sodium or calcium) can usually be separated with simple chemistry, where one metal will precipitate while the other stays in solution. Try that with rare earths and you’ll get nowhere.

Instead, miners and chemists grind up rocks, bathe them in acid, and run the soup through hundreds of rounds of solvent extraction. Each step splits one ion from another — a process so delicate it makes brewing espresso look like rocket science. The reward? A few grams of europium or dysprosium. The downside? Buckets of toxic sludge.

So no, they’re not rare in nature. They’re rare because it takes an industrial chemistry obstacle course just to get a clean sample.

The Bigger Picture

That’s why, when China tightened export rules this fall, European manufacturers had a small panic attack. Prices for neodymium and praseodymium — two MVPs of the magnet world — shot up nearly 40% in a matter of weeks. Washington, Brussels, and New Delhi all vowed action, as if announcing a task force makes chemistry easier. Meanwhile, researchers in Zurich and Toronto are trying to pull rare earths out of yesterday’s junk laptops.

Bottom Line

So the next time rare earths make headlines, remember: it isn’t their scarcity that keeps governments awake at night, but the sheer difficulty of prying them apart. Chemistry, not geology, is what gives China leverage and the rest of the world headaches.

NOTE:

[1] The lanthanides are 15 metallic elements, running from lanthanum to lutetium, that sit in their own row at the bottom of the periodic table. Together with scandium and yttrium, which are thrown in for pity, they make up the “rare earths.” Chemically, they’re so similar that nature — and chemists — treat them as a single family.