Unless you have been sheltered in your bunker, you could not have missed one of the significant discussions around the Big Beautiful Bill (BBB), the impact of a “work requirement” for Medicaid participants. While the opponents pointed to the increased regulatory hassles resulting in disenrollment, the advocates' position might be best summed up by the head of CMS, Dr. Mehmet Oz.

“Go out there, do entry-level jobs, get into the workforce, prove that you matter, get agency into your own life.”

In other words, work isn’t just a paycheck—it’s a moral imperative.

But what happens when the economics don’t line up with the morality tale? The self-imposed deadline for passing the legislation, along with its length, has made it impossible for anyone to fully understand what is in the bill, let alone its potential downstream impacts. Moreover, the haste in fashioning and passing the BBB has meant little opportunity for evidence-based regulatory thinking. A new study in Plos One offers us some hindsight considerations.

The Paradox

The underlying economic debate over a work requirement is simple: Do people prefer working over receiving welfare if the financial rewards are nearly identical? As the researchers write,

“How can countries balance work incentives and access to welfare without violating the principle that work shall always be strictly preferred to welfare?”

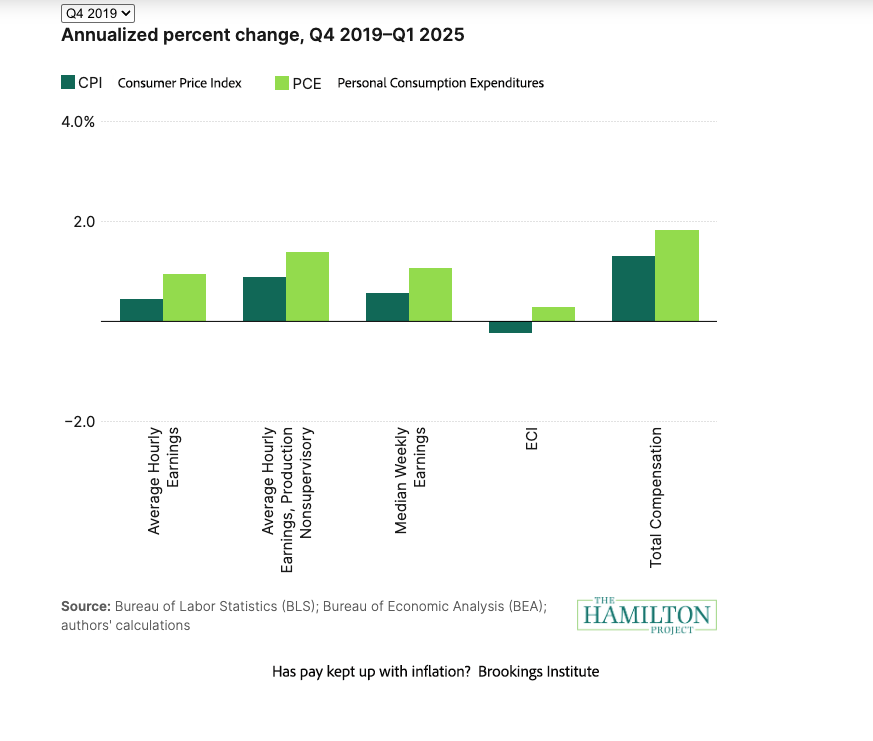

That principle—that working must always “pay more” in both economic and social terms—underpins arguments like Dr. Oz’s. But the real world complicates matters. In the real world, many advanced economies, including ours, have experienced stagnant wages. This is especially true when inflation outpaces wage increases, as has been the case in the US. Simultaneously, there has been a significant expansion of Medicaid eligibility and the amount of benefits available. [1] However, the threshold for eligibility based on the Federal Poverty level may not have kept pace with inflation. [2]

That principle—that working must always “pay more” in both economic and social terms—underpins arguments like Dr. Oz’s. But the real world complicates matters. In the real world, many advanced economies, including ours, have experienced stagnant wages. This is especially true when inflation outpaces wage increases, as has been the case in the US. Simultaneously, there has been a significant expansion of Medicaid eligibility and the amount of benefits available. [1] However, the threshold for eligibility based on the Federal Poverty level may not have kept pace with inflation. [2]

In any event, due to “austerity concerns,” the BBB reduces federal Medicaid payments, shifting that burden onto the states, which are required to maintain balanced budgets, resulting in significant uncertainty about whether benefits will be maintained or reduced. For the sake of conversation, let’s say that in the best-case scenario, they experience a slight decline.

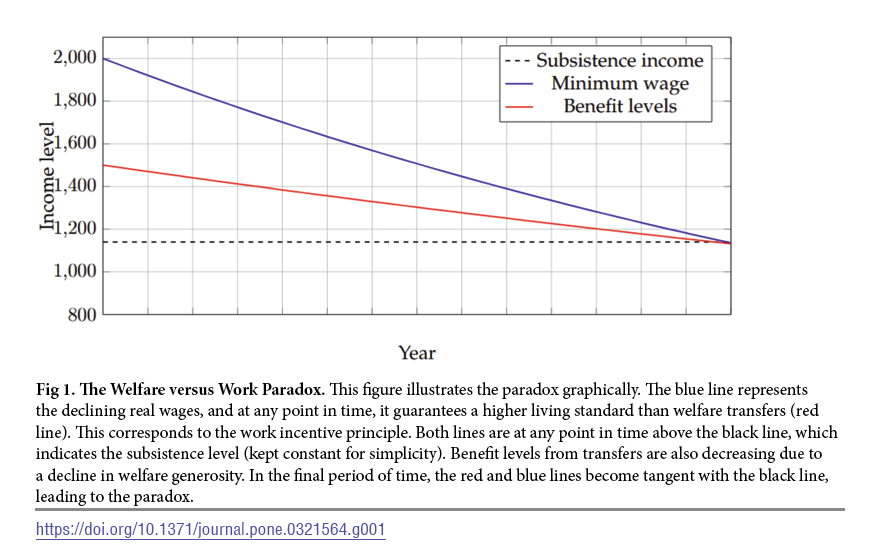

As real wages and welfare benefits converge near the subsistence income threshold, the economic incentive to work erodes. In plain terms: if working full-time earns you only marginally more than government assistance, why choose the harder option?

The authors refer to this as the “welfare–work paradox.”

Modeling the Trade-Off

The research model examines the trade-off between working and relying on welfare, utilizing a simplified setup with two distinct groups: those who work and those who receive welfare without engaging in job searches. Each person has a wage from work and/or receives benefits, both of which are measured against a minimum income level needed to survive. The government can choose to provide benefits above this subsistence level—a concept called welfare generosity. The model assumes that individuals cannot simultaneously combine work and  welfare and instead must choose one path.

welfare and instead must choose one path.

Workers derive utility (read: satisfaction) from income and leisure, minus the effort of labor. Welfare recipients derive satisfaction from leisure and benefits, offset by the effort required to apply for and maintain eligibility. This framework establishes the conditions under which generous welfare might either discourage work or not, depending on how these factors balance out.

A key assumption: the more you work or rely on welfare, the less satisfying it becomes—a nod to diminishing returns. Importantly, the model tests the “work incentive principle”: working must feel more rewarding than not working for the system to function.

As it turns out, that assumption breaks down quickly if:

- Minimum wage hovers around the poverty line

- Welfare benefits provide similar income with less effort

When both options yield approximately the same income, people may naturally prefer welfare, contradicting the belief put forward by Dr. Oz, among others, that work should always be more rewarding than not working. The harder work feels (or the faster its value seems to wear off), the more likely people are to favor welfare. As the graphic demonstrates, the gap between minimum wages and benefits closes as the “bonus” in greater income for working diminishes.

Now, opponents of work requirements will argue this will result in individuals “thrown off” Medicaid, while advocates of work requirements will say “good riddance” to able-bodied freeloaders. However, the cost of healthcare for these individuals will ultimately be paid by taxpayers, and we may want to consider that, as MAHA argues, preventative care is far better than treating chronic illnesses. From a policy point of view, the model

“…suggests that, for the work incentive principle to remain valid and govern incentives in the right direction, minimum wages must be set and maintained consistently above the subsistence threshold.”

The minimum wage in the US is $7.25 per hour and has not been adjusted since 2009. It amounts to an annual income of roughly $14,500, below the federal poverty level for a single individual of $15,650. Interestingly, Washington, DC has the highest minimum wage in the country at $17.25/hour or $35,900 annually. Of course, when we consider families receiving Medicaid benefits, the average size is 3.7 individuals, and the federal poverty guidelines for a family of four are $32,150. That $3,000 wage advantage isn’t exactly a compelling reason to clock in every day, especially if job conditions are poor and benefits remain stingy.

As study author Roberto Iacono writes:

“The work incentive principle no longer works when both the minimum wage and welfare benefits are so low that the financial return from both approaches is close to the subsistence level.”

A Question of Priorities

The model suggests that the minimum wage must exceed the subsistence level by enough to:

- Justify working over welfare

- Allow for modest welfare generosity

- Create a real incentive structure

That’s not ideology. That’s economics.

Perhaps the better path isn’t telling people to “get agency into your life” by chasing low-wage, no-benefit jobs, but offering living wages that can support a household. Because in the long run, preventative care costs less than crisis care. And dignity, unlike Medicaid, shouldn’t require paperwork.

[1] Much of those benefits are accruing from States gaming the Federal funding through provider “taxes.”

[2] The official poverty threshold for the US is “three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963,” adjusted annually by the Consumer Price Index. This has resulted in a slight drop in the official poverty rate to 11.1%. An alternative measure, the supplemental poverty threshold, is defined as 83% of the total spending of a median consumer unit on food, clothing, shelter, utilities, telephone, and internet. It has resulted in a slight increase in the poverty rate to 12.9%.

Source: The Welfare versus Work Paradox. PLoS One DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.032156