The mainstream medical community and most Americans still champion vaccines, and all states require childhood vaccinations, although exemptions for religious and medical reasons exist. While resistance has always been part of our culture and legal history, attempts to expand the ability to say “no” haven’t fared well until recently. Even more substantial and more effective pushback is still on the horizon.

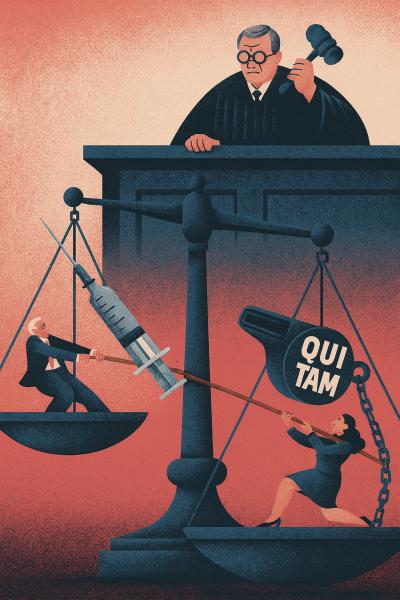

Anti-vaxxers have enlisted an unusual ally –the trial lawyers. Armed with a cauldron of novel theories, buttressed by citizens espousing medical freedom (who vote for State Court judges), and bankrolled by the expectation of opening financial floodgates, new varieties of lawsuits are mushrooming alongside recent anti-vax decisions that run counter to a long history of judicial veneration for vaccines.

Creative Claim Repurposing

While claims championing individual or religious freedoms over public health are the tried-and-true mode of attack, the plaintiffs’ bar has gotten creative. One new approach is the repurposed qui tam suit, originally designed to prevent fraud when entities submit invalid, fraudulent, or flawed claims for federal reimbursement by allowing private plaintiffs (called relators) to sue on behalf of the government under the False Claims Act (FCA). The cases are dubbed “whistleblower” suits since they allow “insiders” with knowledge of sub-optimum practices to “rat” on employers without fear of retaliation.

After instituting the case, the federal government can investigate the relator’s claims. It may choose to intervene and prosecute the FCA claim as a full-party plaintiff, or decline intervention, leaving the relator to prosecute the action on behalf of the US (and to seize any money awarded).

The method has been appropriated in recent product liability litigation. The Zantac litigation spawned an offshoot qui tam case, in which the plaintiff (here, a private laboratory) claimed that the Zantac manufacturers defrauded the government by failing to conduct appropriate testing, which they argued demonstrated that the product degraded into dangerous by-products. The case settled for $2.2 billion.

Not all such qui tam claims have been successful. In one, Dr. Clarissa Zafirov sued her employer, alleging it violated the FCA by misrepresenting patients’ medical conditions to Medicare, thereby obtaining greater reimbursement than what was truly owed. Dr. Zafirov lost at the pleading stage, as the court held that this brand of litigation wasn’t meant to enrich individuals, and Judge Kathryn Mizelle ruled that the provision empowering private litigation was unconstitutional.

“[N]o one — not the President, not a department head, and not a court of law—appointed Zafirov to the office of relator. Instead, relying on an idiosyncratic provision of the False Claims Act, Zafirov appointed herself. This she may not do.”

–Judge Kathryn Kimball Mizelle

This has not deterred the budding use of qui tam claims in COVID vaccine cases. Riding on recent contested and controversial FDA declarations that the COVID vaccine is dangerous and responsible for the deaths of ten children, we are regaled with the case of Conrad v. Rochester Regional Health.

In Conrad, a physician’s assistant claimed her former employer committed fraud against the federal government when accepting vaccine reimbursement while failing to report Covid vaccine side effects. The crux of Ms. Conrad’s case is that during her employment with Rochester Regional Health (RRH), she observed her employer submit payment for thousands of claims despite failing to report adverse claims through VAERS [1], as required by its Provider Agreement in dispensing Pfizer’s Covid vaccine. While the court acknowledged the vaccine's effectiveness and comparative safety, and recognized the public and independent reviews to which vaccine trials were subject, it nevertheless allowed the case to proceed on allegations that over 100 serious adverse events were not reported.

That allegation is not sufficient to sustain a FCA claim; Fraud and recklessness must be present as well. In Conrad, sustaining the fraud element was a reach, inferred from the allegation that RRH wanted to prioritize high vaccination numbers over mandatory safety monitoring. That will have to be proven for the plaintiffs to prevail.

For now, this case holds that alleging failure to report material adverse events to VAERS with sufficient particularity (which the court believes would have enabled the CDC and FDA to “quickly identify potential health conditions and ensure vaccines are safe”) is sufficient to maintain a FCA claim, assuming the failure to report is provably intentional or fraudulent.

Sadly, the court is mistaken. Reporting to VAERS, while informative and useful, does not provide the opportunity for immediate assessment of vaccine safety. That function is sustained during clinical trials, carefully reviewed by the FDA before authorization is afforded, and augmented by the Phase IV portion of the trial, which evaluates post-marketing events. Should the holding be sustained on appeal and thread its way to other jurisdictions, the qui tam action could chill vaccine uptake, based on this mistaken impression by the court.

Additionally, Ms. Conrad was able to advantage herself of FCA protection for retaliatory firing, which she claims triggered her dismissal. The defendants disagree, claiming she was terminated for failing to get a COVID vaccine. As the case plays out, the credible facts determining the circumstances of Ms. Conrad’s termination will emerge. For now, we might worry that the case invites anti-vaxxers or vaccine skeptics to infiltrate sensitive establishments and look for what might be considered violations, instituting lawsuits to harass the defendant, and impair vaccine accessibility by deflecting providers’ attention from protecting the public to protecting themselves from liability, all while they take advantage of whistleblower protection.

Indeed, that is precisely what happened in Brooks Jackson v. Ventavia Research and Pfizer, where Ms. Jackson secured employment at a group facilitating Pfizer’s clinical trials – seemingly for the very purpose of securing a FCA against companies involved in vaccine manufacture and securing FDA approval, a practice ostensibly beginning on day one of her employment.

“Here, beginning on September 8, 2020—the day Ms. Jackson began her employment at Ventavia—she reported “on a near-daily basis” to Ventavia management that “patient safety and the integrity of the [Pfizer] vaccine trial was at risk.”… she regularly reported violations of trial protocol, FDA regulations, and HIPAA to Ventavia management.

Jackson raises a similar issue to Conrad: specifically, that Pfizer’s protocol certified it would conduct the clinical trial in accordance with all applicable laws and regulations, which Ventavia allegedly and recklessly, or fraudulently, failed to do. The United States not only declined to intervene in the action against Pfizer and Ventavia but also joined these defendants in seeking dismissal of the matter.

The court agreed with the defendants, reiterating that the FDA fully approved Pfizer’s vaccine, has not revoked its approval, continues to provide the vaccine to all citizens free of charge, and “repeatedly concludes that it has not been defrauded” even after being aware of the whistleblower allegations.

Explaining the 180-degree difference in political and judicial determinations in the cases is challenging. In Conrad, the government chose to sit the matter out and let the relator pursue the case with the court's approval; in Jackson, not only does the court reject the claim, but so do the Feds, who join with the named defendants to seek dismissal.[2]

Perhaps the key to the Jackson determination lies in the court’s rejection of Ms. Jackson’s whistleblower claims, noting:

Congress,..., “enacted the FCA to vindicate fraud on the federal government, not second-guess decisions made by those empowered through the democratic process to shape public policy.”

The court found that Ms. Jackson was “not concerned about, or alerted Ventavia or the FDA to, potential “fraud against the government… [but] rather, she …. complain[s]… about participant safety and regulatory, protocol, and HIPAA violations.”

In sum, the Jackson court, much like Judge Mizelle, states “that … protected activity under the FCA’s retaliation provision— [such as] internal complaints about patient safety, or protocol and regulatory violations, are not the same thing as complaining about defrauding the Government.

Where We Go From Here

The two cases are both on appeal and pending in different jurisdictions. Should the appellate courts continue to diverge in their holdings, we should expect the Supreme Court to sound in. Will public health or politics prevail?

[1] VAERS, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, is a "national early warning system to detect possible safety problems in vaccines used in the United States."

[2] It is worth noting that Conrad involves a defendant-state agency, and the case alleges active harms to safety. In contrast, in Jackson, the FDA is attacked, with the alleged violations being more ministerial (e.g., HIPAA violations, unblinding deficiencies, regulatory violations involving breaches of clinical trial protocol). In both cases, however, allegations were raised that adverse effects were not reported. Also, the alleged violations of clinical protocol directly affect safety and efficacy determinations.