When does difference become a disability, and disability become a disease? Words have powerful meanings. Disabilities come with certain new legal rights, diseases come with funding for researchers and socioeconomic support for the afflicted; differences, however, provide not as much social “juice.” This tension arises not only in autism, but also in conditions like obesity or long COVID, where the boundaries between difference, disability, and disease remain contested.

On the Spectrum

Autism provides a particularly vivid case study of these shifting boundaries. Individuals on the autism spectrum, a term used to describe the wide range of signs and symptoms associated with autism, share some commonalities.

- Difficulties with social communication

- Love of repetition,

- Distress in the face of unexpected change

- Hyper and hypo-sensitivities to stimuli.

There are additional co-morbidities, fellow-travelers for those on the spectrum, like gastrointestinal pain or ADHD. These conditions that often co-occur with autism further complicate the boundaries between difference, disability, and disease. [1] Given even small variations in the basic findings of autism create a large range of human behavior.

Individuals with reasonable communication skills, at the most “functional” end of the spectrum, chafe at being described as having a disease, in many cases preferring to characterize their differences as diversity – a less demeaning term. However, when and how do “differences” become disability?

Boundary Conditions

Body size is an easily recognized difference; anyone who has been in the presence of a professional football or basketball player recognizes those differences. To recognize how height becomes a disability, we need only consider Alice in Wonderland, where Alice is too small to reach the doorknob and too large finding herself stuck inside the lizard’s cottage. Dis-ability requires context; one environment may be more challenging to one’s abilities than another. Perhaps disability can be defined by the alterations necessary to reduce the challenge.

A wheelchair bound person is fully able to navigate a city sidewalk, until they reach that six-inch curb. The curb is the context for the disability; a sidewalk cutout offers the accommodation that reduces the challenge. [2] Similar boundary conditions emerge in obesity, where environments designed for smaller bodies, e.g., airplane seats, turnstiles, clothing sizes, transform a visible difference into functional disability.

The frontier between disability and disease is even less clear. A person with autism, who is minimally verbal, with a vocabulary of about 30 words, might be considered severely disabled, while another individual with a greater vocabulary is not. However, if the latter individual also has a severe sensitivity to light or sound, that may make using the expanded vocabulary difficult or impossible. Different traits interact with one another, creating greater or lesser degrees of functional impairment; we err when we associate a medical condition with a specified degree of impairment.

There are a number of classification schemes to overlay functional impairment on a specific disease. For example, there is the New York Heart Association classification of heart failure, which serves in creating meaningful characterizations of patients for treatment who lie upon a spectrum of disease. This illustrates how medicine already uses spectrum frameworks, yet autism remains more socially contested.

Why then is there controversy within the community of individuals on the autism spectrum? The answer that readily comes to mind is the stigma we attach to some illnesses, especially mental or cognitive illnesses. More deeply, much of the tension surrounding autism may come from two competing models, the medical and the social.

Medical Model to Social Model

The medical model views autism as a pathology located within the individual. As a disease, patient-borne challenges are framed as deficits requiring treatment or remediation. In contrast, the social model argues that many “impairments” are products of an environment designed for a neurotypical majority. Under this view, fluorescent lighting, open-plan offices, and cacophonous classrooms disable far more than atypical sensory processing ever could.

Long COVID illustrates another dimension: a cluster of fluctuating symptoms that resist neat medical classification. For some, fatigue or brain fog is disabling, yet without clear biomarkers, recognition and support remain contested.

Neither model alone is sufficient. Severe gastrointestinal pain or self-injurious behaviors, co-occurring with autism, are undeniably biomedical problems that warrant treatment. Yet difficulties with eye contact or a passion for collecting transit maps are not pathologies at all; they are variations rendered problematic only by social expectation.

How we label a condition moves dollars. The Americans with Disabilities Act unlocks accommodations in school and work, and protection from discrimination, if the individual carries a recognized disability label. Research dollars from the NIH or private foundations often hinge on a condition being classed as a “disease” with measurable biomarkers and treatment endpoints. These incentives encourage “medicalization” on one hand and gatekeeping on the other: families lobby for clinical labels to access services, while patient-advocates resist terminology implying they are broken and in need of fixing.

We see similar tensions arising in our language. Are we identity-first, describing an autistic person or a diabetic? Or person-first, the woke-tainted person with autism or diabetes. Both seek respect, autonomy, and resources to thrive, the former under a medical banner, the latter as a part of their “nature.”

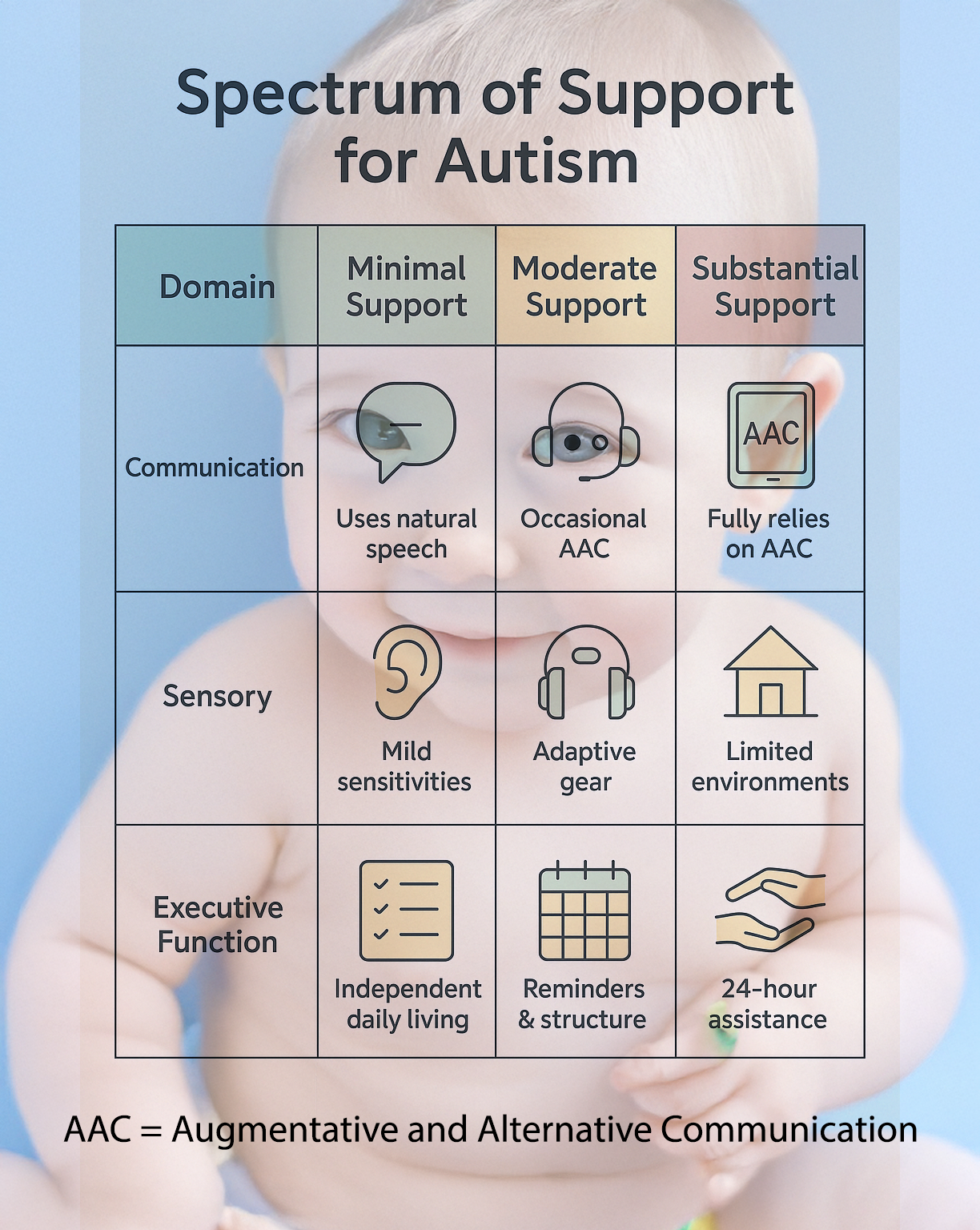

The clarity of terminology should never overshadow the urgency of providing adequate care, inclusive education, or meaningful employment. A more nuanced approach would consider autism as a spectrum of support requirements.

By mapping concrete support needs rather than assigning a monolithic label, we sidestep “punitive” characterization of “high” versus “low” functioning. We make “room” for a coder who writes elegant software yet cannot tolerate a fluorescent bulb’s hum, or the non-speaking poet who types vivid free verse.

Perhaps the most productive path forward is a hybrid medical-social model that acknowledges legitimate biomedical burdens while insisting that society carries a responsibility to adapt. Curb cutouts were once considered deluxe add-ons; today, they are mandated infrastructure.

Difference becomes disability when environments, attitudes, and systems are inflexible. Disability becomes disease when biological distress demands clinical intervention. Autism spans all three states: difference, disability, and sometimes disease, often simultaneously within the same individual. The same is true for other contested conditions. Obesity, for example, is simultaneously a visible difference, a disability when it interacts with environments built for smaller bodies, and a disease when it gives rise to metabolic or cardiovascular complications. Long COVID, by contrast, illustrates how an ill-defined syndrome can fluctuate between different, disability, and disease depending on the presence of fatigue, brain fog, or respiratory compromise, and the willingness of society and institutions to provide recognition and support.

Recognizing this complexity honors both the lived experience of autistic people and the genuine medical challenges some face. It underscores the need for flexible categories that map biological distress and social barriers—so that care, accommodations, and dignity follow the person, not just the label.

[1] It was the gastrointestinal pain of autism that provided the basis for Dr. Wakefield’s appropriately discredited work, which has been the source of “evidence” for the anti-vaxxer community.

[2] As an assistive design becomes more ubiquitous, it finds a place in the lives of the less disabled, in this instance, for bicycles, children in strollers, and those who might be navigating the city with a cane or walker.

Source: The Concept of Neurodiversity Is Dividing the Autism Community Simon Baron-Cohen Scientific American