In addition to the nearly 3,000 Americans lost on that day, more than 91,000 responders were exposed to various hazardous materials on 9/11 and during the subsequent recovery and cleanup. The World Trade Center Health Program was set up to care for the continuing health needs of those responders. Here is a look inside the data.

The data includes information on 80,745 responders. 77% are categorized as general responders—police, ambulances, rescue, and recovery teams. 21% were New York’s Bravest, the New York Fire Department firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. They all were, in their own way, first responders, but the distinction is made because the exposure to hazardous materials declined over time. So the “doses” are impacted by the time on “the Pile” and how soon after the attack exposure occurred.

In addition to that caveat regarding dose-exposure, the researchers point out that a variety of lifestyles and choices, i.e., smoking, make causal links tentative and “viewed with some caution.” As you might expect, most responders with health issues were male, 83%, and young, with an average age of 45-64. (Remember there is a 20-year lag in age)

- The most common ailment is “aerodigestive” disease, which occurs in the mouth, throat, or lungs. Asthma is by far and away the most frequent problem, followed by a chronic cough and sinusitis.

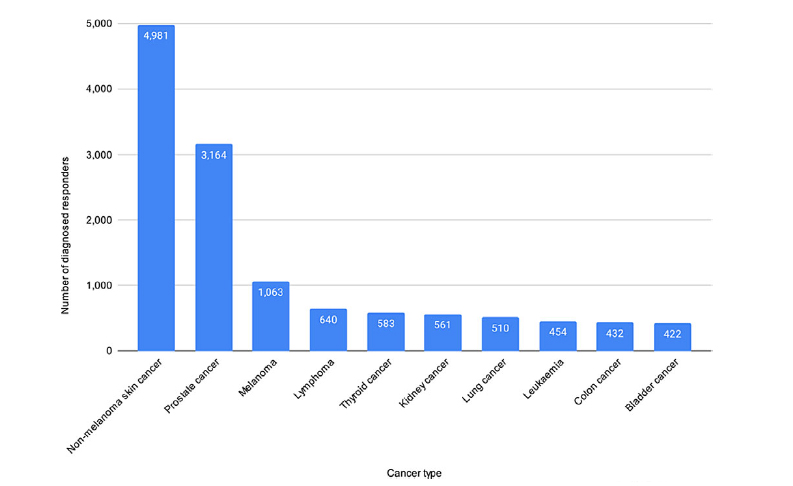

- With time, there is an increasing incidence of cancers—a 185% increase in the last five years.

- The rise in prostate cancer is particularly problematic as it usually is a disease in older men. Many of the cases among the responders are in younger men and with more “aggressive” appearing cancers with greater evidence of expression of “immunologic and inflammatory” genes. Could hazardous materials inhaled on and around ‘the Pile” initiated that chain of events?

- The data focused on the firefighters suggest a statistically significant but modest increase in excess cancers compared to the general public. But when these same findings were compared to firefighters in Chicago, San Francisco, and Philadelphia, there were no longer excesses. Fire-fighting brings its own more prolonged exposure to hazardous inhalants. Firefighters who arrived on September 9 were 44% more likely to have cardiovascular disease than those arriving the next day. You can see how important it is to identify the time and duration of exposure if 24 hours makes such a difference.

- Responders have roughly a four-fold increase in the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to the general public, 15-20%. And unlike other studies of PTSD, the prevalence seems to be increasing with time. Research outside this data set suggests that PTSD and depression have an underlying cognitive basis, “including difficulty recalling names and words, and a greater reliance on written reminders.” Mental health frequently is a hidden problem, and this case is no exception. Nearly 50% of 9/11 responders report an “on-going need for mental health care.”

As the nation pauses to remember 9/11 on this day, the 20th anniversary, we should remember not just the losses and actions of our first-responders. We should acknowledge that for many of them, 9/11 is an ongoing attack on their health and life.

“Whatever we got wrong, we should acknowledge, and people should be helped.”

Christine Todd Whitman, 2016

Source: Health Trends among 9/11 Responders from 2011– 2021: A Review of World Trade Center Health Program Statistics Prehospital and Disaster Medicine DOI: 10.1017/S1049023X21000881