“… pharmacists are experts at recognizing and avoiding drug-drug interactions.”

That is undoubtedly true, but they have no training in prescribing care – and Paxlovid is very effective, but just one option. Molnupiravir, as Dr. Bloom has pointed out, is not as effective but is flying off the shelves because it is more readily available. There is also bebtelovimab, a monoclonal antibody approved for use against the omicron variant, but that requires an infusion. Most importantly, with any infectious disease, well, with any illness, follow-up to gauge the efficacy of therapy and the need for additional interventions is critical. Pharmacists are not giving follow-up appointments; they dispense medications, not care.

Dr. Singer is correct that the AMA and other physician organizations have been very concerned about the expanding scope of practice of nurse practitioners and physician assistants – but that is a different concern. Both nurse practitioners and physician assistants have training in treating illness; pharmacists do not. Nor do they currently have insurance coverage for the act of prescribing. Pharmacists are administering vaccines because their states have allowed it under defined circumstances.

There are other options to facilitate “test and treat,” but they all involve one of those individuals trained in caring for illness, not just dispensing medication. And all, unfortunately, charge an additional fee. (Pharmacists would also like to receive more than the $6 dispensing fee they now receive).

The Ecology of Medicine

There is a structure to how we have organized care. Primary care physicians care for our day-to-day and chronic illnesses while helping us navigate the landscape to find specialists and hospital care when that is needed. In the last few years, the “disrupters” have sought to provide the day-to-day needs of patients, what I would call the “lump and bump care of the walking well” (sore throats, earaches, sprains) in alternative, more convenient settings and at lower price points.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the acceptance of telehealth in place of office visits. A variety of online websites now prescribe medications (birth control, erectile dysfunction medications) and medical devices (CPAP machines) that involve online “examinations” and prescriptions by licensed physicians. Urgent care centers, both freestanding and those within pharmacy walls, provide care and medications simultaneously under the direction of a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant. Here is the result of that disruption.

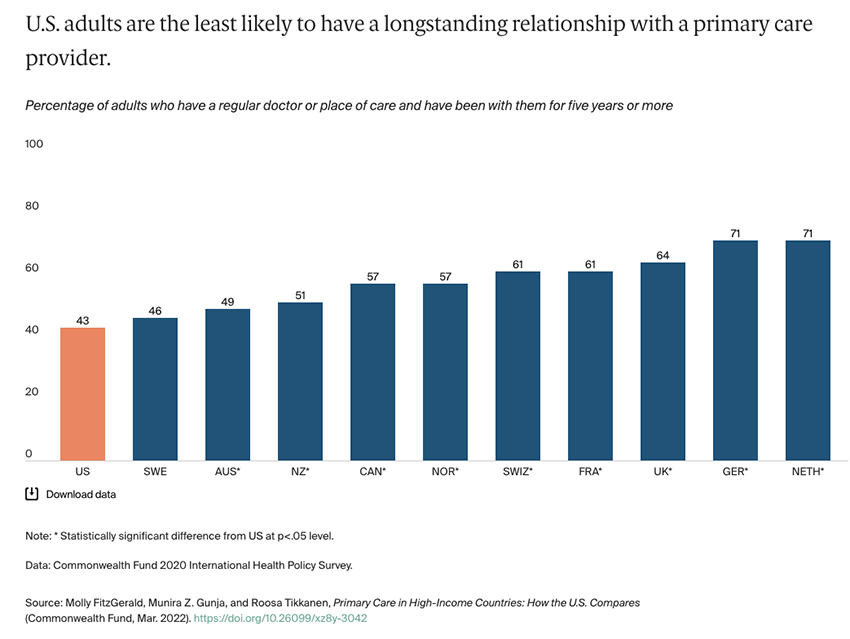

Few of us have a primary care physician, such as a gynecologist, cardiologist, internist, or family practitioner, that we see regularly enough to build a relationship. And these physicians are our health Sherpas – knowledgeable of the landscape of disease, with its pitfalls and nuances; and aware of your abilities and blindspots. You wouldn’t attempt to climb Everest without them. Ultimately, because you are connected by a rope, you must trust them with your life. While that may be a bit dramatic an analogy for a primary care physician, that rope, that trust, is built from many smaller, lower risk encounters. A consistent health Sherpa results in better care.

Continuing to offload simple care to less expensive providers will, in the ecology of medicine, result in the end of primary care physicians. We should be careful what we wish for, because as Joni Mitchell wrote, “you don't know what you've got till it’s gone,”

Other sources you might want to consider in forming your opinion:

A Successful 'Test-to-Treat' Program Requires All Hands on Deck