Is it possible to ever persuade the politically-polarized segment of the vaccine-resistant population to take the jab – thereby avoiding mandates? According to research gathered by Ezra Klein for his book, Why We’re Polarized, the answer is a resounding: No.

The Politicization of Vaccination: A Bit of Political History

As world leaders stepped up to get COVID- jabbed, Trump lolly-gagged and beleaguered his experts. The behavioral message was not lost. Even early surveys revealed that Republicans lagged in vaccine uptake while Democrats headed the list.

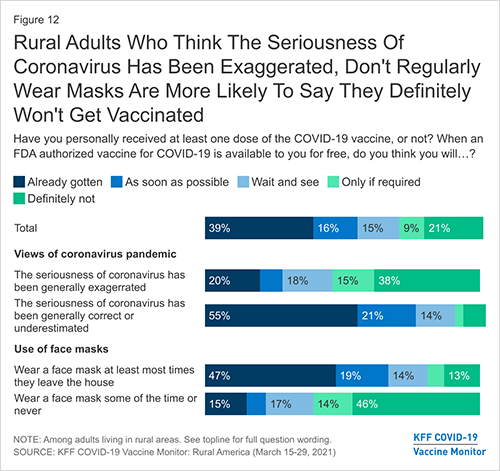

While some adopted a wait-and-see attitude, others, mostly Republicans, said they would definitely not get vaccinated, meaning they would be immune to any persuasion campaign; hence mandates would be necessary if we wanted to increase vaccine uptake. Indeed, by April 2021, 30% of Republicans said they would definitely not get vaccinated. Another group said they would be vaccinated only if required.

“Large shares of those who say they will “definitely not” receive a COVID-19 vaccine self-identify as White Evangelicals (41%) and Republicans or Republican-leaning independents (73%).”

Rural Republicans awaited the word from their Commander-in-Chief. They waited and waited. Republican anti-vaccine behavior has resulted in a staggering disparity in deaths, reported just last week.

Rural Republicans awaited the word from their Commander-in-Chief. They waited and waited. Republican anti-vaccine behavior has resulted in a staggering disparity in deaths, reported just last week.

You get what you pay for

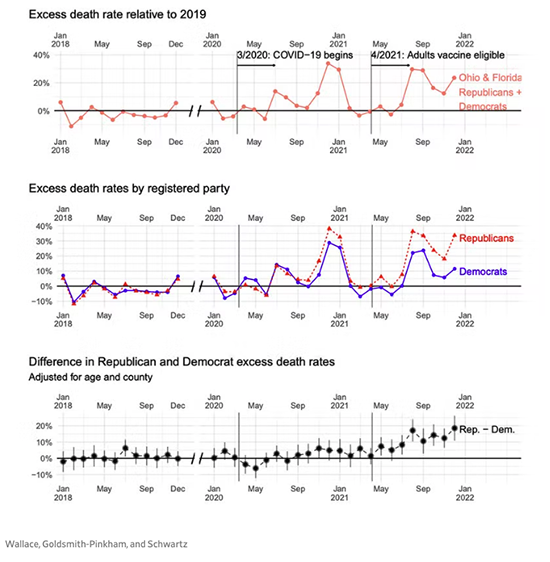

A working paper released by the National Bureau of Economic Research reported that between March 2020 and December 2020, excess deaths in Florida and Ohio were 76% higher among Republicans than Democrats. A Yale study found that between April and December 2021, when all adults first became eligible for the COVID vaccine, the gap widened further: Excess death rates in Florida and Ohio were 153% higher among Republicans than Democrats.

“the graphs … show the gap between Democrats and Republicans turned noticeable only after vaccines became widely available. In other words, absent the vaccines, the effect of partisan ideology was not very large. But once people could choose to protect themselves with a shot, Republican and Democratic outcomes diverged.”

Researchers don’t just blame vaccine recalcitrance for the gross disparity. Failure to mask and adhere to social distancing also contributed to the difference. But these measures, too, were politically driven.

“At this point, it seems safe to say that one of the key reasons why the U.S. failed where other countries succeeded is because right-wing leaders and media sought to sabotage the [vaccination] effort—in particular by casting doubt on the effectiveness and safety of vaccines.”

Politics and Persuasion

What is it about a political ideology that governs vaccine resistance? After all, being a Republican used to mean financial conservatism, not a rejection of generally accepted public health policy. (Even social liberties were once acceptable to Republicans, at least to those who remember Rockefeller and his generation of Republican leadership).

As Ezra Klein writes in his book, Why We’re Polarized, politics today has become the divining rod in our life decisions. And that’s where we run into trouble. Public health policy is now interwoven with politics. Once a party leader embraces a public health position, from ignorance, contrarianism, to demarcate themselves from the “other” (aka Democrat), to pander to the libertarian element of the party, or to prove their religious bona fides, party-adherents across the spectrum adopt the position. Fear of being cast as an outsider prevents independent assessment and blocks open-minded discussion.

Klein’s work establishes that our identity is now powerfully shaped by our politics. By adopting a specific political mindset, we achieve a sense of camaraderie, identity, support, and community. Fear of losing that “kith and kin” prevent persuasion in a rather absolute fashion, even of positions not traditionally party-related, such as vaccines, lockdowns, or masking. Per Klein’s research, neither facts, data, analysis, nor expert opinions will change that mindset. The extremism fostered by a politicized identity blinds us to “scientific beliefs” and political opinions.

How politics makes smart people stupid

Persuasion can only work in emotionally or politically neutral situations, which is not the case here. What matters to the political-aligned is being ideologically compatible, not being factually correct, i.e., finding answers aligning with one’s preconceived political notions. Here’s one example of research establishing this premise:

A thousand individuals who self-identified as liberal or conservative were given a simple, emotionally-neutral math problem. The ability to answer the question tracked the individual’s mathematical ability. A second version of the same problem politicized the numbers, comparing crime in cities that banned handguns versus crime data in cities that did not. The results, surprisingly, differed, even though the problem, mathematically, was identical.

“Liberals were extremely good at solving the problem when doing so proved that gun-control legislation reduced crime. But when presented with the version… that suggested gun control failed, their math skills stopped mattering…. Conservatives exhibited the same pattern in reverse.”

One researcher termed this effect “identity-protective cognition.” To avoid cognitive dissonance and estrangement from groups that the individual values, they “subconsciously resisted factual information that threatens [to destroy] their defining values.”

“Being better at math didn’t just fail to help partisans converge on the right answer - it drove them further apart. People weren’t reasoning to get the right answer, they were reasoning to get the answer they wanted right.”

Those advocating persuasion (and opposing mandates) believe that exposure to scientific truth will work. The research shows that it does not, at least not in this group. It appears that hearing contrary opinions drives partisans to even more profound certainty in the rightness of their cause. Studies have shown that after hearing moderating views, “Republicans became more conservative rather than more liberal and Democrats, if anything happened, became more liberal rather than more conservative.”

The echo chamber of polarization

Whether consciously or not, we choose information sources that corroborate a pre-existing notion. Klein calls this the “echo chamber of polarization.”

“We’ve cocooned ourselves into hearing information that only tells us how right we are, making us more extreme.”

Other experts tell us that “once group loyalties are engaged, you can’t change people’s minds by utterly refuting their arguments…. Thinking is mostly just rationalization, mostly just a search for supporting evidence.” In sum, Klein’s research reveals that changing someone’s mind once it’s affixed to a political identity is – impossible. This applies to scientific issues, such as climate change, as well as rank political ones.

“[On] highly politicized issues, people’s actual definition of “expert” is a credentialed person who agrees with me.”

Rather than more evidence or knowledge affecting opinions on scientific matters, such as climate change, researchers found “that among people who were already skeptical of climate change, scientific literacy made them more skeptical of climate change.” [emphasis added].

Another researcher explained: “the more information …[one] has, often the better able she is to bolster her identities with rational-sounding reasons,” meaning our reasoning capacity quickly becomes rationalizing when dealing with questions that could threaten our group, or at least the social standing in our group. Being correct on an issue is less important than being part of a group.

The Trump Effect

Early on, there might have been a time when Trump could have sent the message that moved his party. No longer.

In fact, Trump’s initial anti-vax tweets were associated with increased anti-vax sentiment. But it took until April of 2022 for the phenomenon to be identified. Early on this might have been countered had Trump changed his stance. Researchers found that compilations of former President Donald Trump’s Fox News interview recommending the COVID-19 vaccine were able to overcome some anti-vax sentiment. Sadly, Trump’s initial position became entrenched in the party line.

Today, former President Trump finds himself like the sorcerer’s apprentice, wielding a power, like the brooms fetching water, that he can no longer control. After being the first President on record with anti-vaccine sentiments, Trump belatedly seemed to come around. In December of 2021, Trump about-faced and revealed a lukewarm embrace of boosters (which has only a 40% US uptake, compared to 70% in, for example, the UK). But the prior mindset had already stuck. Trump was booed by his base, which rejected him, vilified him, and generated the feared backlash of group ostracism.

In sum, for the great majority of those averse to vaccination, that aversion is politically-driven. And for that cohort, persuasion won’t work. It’s time to start noticing the nuances and stop pining for a perfect world.