What exactly is Ozempic?

Ozempic is a brand name for semaglutide, an analog or biosimilar [1], for a human hormone, GLP-1 – glucagon-like-peptide. It reduces blood glucose by simultaneously stimulating insulin secretion, which is why it is effective in Type II and not Type I diabetes, and lowers glucagon secretion; it also slows the emptying of the stomach slightly. It is not a first-line medication for Type II diabetes, and most forms require a weekly injection.

As with all medications, there are adverse effects. Ozempic comes with a black box warning, the FDA’s highest safety warning, for the possible development of medullary thyroid cancer and multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN-2). [2] The other adverse effects are limited to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation, and a small percentage of cases of hypoglycemia (a blood sugar lower than 70 mg/dL) which can be lethal but has not been the case, so far, with Ozempic. Of course, the problem with all of these other adverse effects is that they were found in individuals with diabetes, and many of the people seeking and using Ozempic off-label, do not have that condition.

Weight loss

The thought that semaglutide might be used as a weight loss drug dawned during its Phase II trials when it resulted in weight loss in patients with diabetes as well as those with obesity. Its serendipitous “discovery” as a weight-loss aid mirrors bariatric surgery, which is founded on the finding that patients undergoing stomach (gastric) surgery in the 50s for ulcer disease all lost weight.

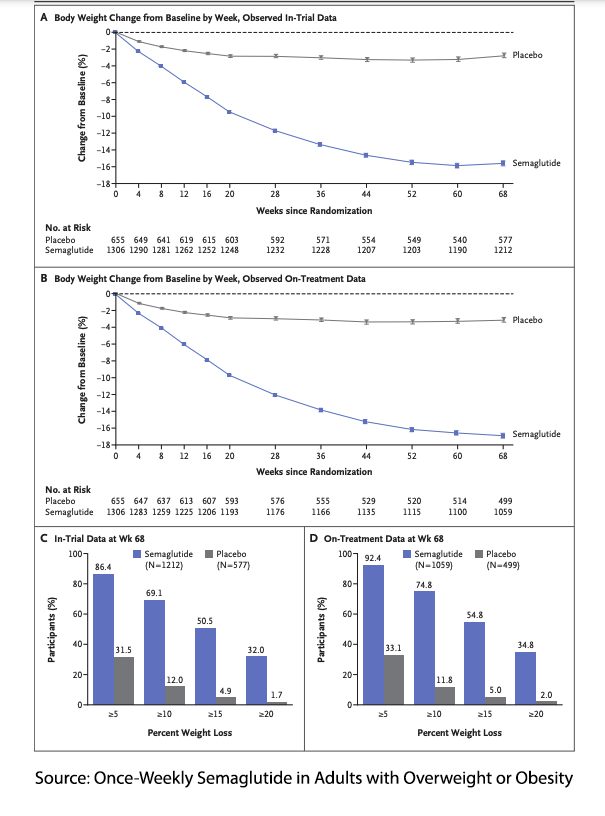

A study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine of roughly 2000 obese (BMI>30) adults without diabetes showed a nearly 15% loss in individual weight at 68 weeks compared to 2.5% for the placebo arm. Almost 90% showed mild to moderate adverse effects seen previously in those patients with diabetes, but this was mirrored by a statistically similar percentage in the control group.

A study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine of roughly 2000 obese (BMI>30) adults without diabetes showed a nearly 15% loss in individual weight at 68 weeks compared to 2.5% for the placebo arm. Almost 90% showed mild to moderate adverse effects seen previously in those patients with diabetes, but this was mirrored by a statistically similar percentage in the control group.

Unlike other weight-loss agents, the reductions in weight with semaglutide were clinically significant in terms of the patients’ perception of their well-being and the reduction of cardiovascular risk.

Wegovy

This brand name for semaglutide is approved for weight loss. Its medical indication comes from a study similar to the one reported on patients with diabetes, but in this case, the patients did not have diabetes. More importantly, their weight loss was a bit less than with Ozempic, 12.5%. The safety profile is identical to that of Ozempic, as are the black box warnings. Wegozy comes in a slightly higher dosage but continues with the once-weekly injections. Their prices are comparable, over $1000 a month.

One More Fly in the Ointment

“One year after withdrawal of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg and lifestyle intervention, participants regained two-thirds of their prior weight loss, with similar changes in cardiometabolic variables. Findings confirm the chronicity of obesity and suggest ongoing treatment is required to maintain improvements in weight and health.”

That is the conclusion drawn by researchers who extended that trial of semaglutide in patients with diabetes. They followed 327 of those participants for an additional year and found that much of the weight returned. For comparison, bariatric surgery patients also experience regaining weight, although more in the range of 10 to 25%.

The bottom line for all those seeking medication for weight loss is semaglutides may be your answer, but you will have to take them chronically. At the cost of roughly $12,000 annually, bariatric surgery may remain a better long-term bargain. For those on Tik-Tok, or in Hollywood looking for acute weight loss, Ozempic and Wegovy are the same; why bother with the off-label version? More than likely, they may want to save a few dollars; Wegovy is prescribed at a slightly higher dose than Ozempic, and that translates to a $200 or so difference in price, favoring Ozempic For those of you with an economic bent, the rapid increase in demand for Ozempic and Wegovy has created shortages of both.

Off-label marketing

There is little doubt that much of the demand for these drugs has been fueled by the influencers on Tik-Tok, where the Guardian reports over 74 million views, and by celebrities, including our new master of all media, Elon Musk.

The FCC regulates drug advertising, and among approved ads are those designed to heighten public awareness around medical conditions. That helps explain so many ads discussing thyroid eye disease or vasomotor symptoms ( the medical term for hot flashes) associated with menopause. There is, as you might expect, a thriving series of ads heightening our awareness of obesity with a link to treatment options. The most interesting feature Queen Latifah as reported by Fierce Pharma

“In the crime sketch, she plays a detective who presses a witness to give up the goods on “the perp”—seemingly obesity—though it's never mentioned in any of the videos by name. (The company's research found the audience would tune out at even the sound of the word.).”

In the final segment, shot in a dressing room, Queen Latifah breaks character and speaks directly to the audience.

“I’ve experienced being judged by others because of my weight. I know the negative effect it can have on you,” she says. “But I never let that stop me, and neither should you.”

Yes, commercials designed to reduce the shame of obesity, indicating that it is a health condition, not a problem of willpower and simultaneously directing possible patients to treatments. They are brilliantly conceived. Oddly you never hear anyone discuss the possible conflicts of interest that this educational material from Novo Nordisk, the makers of Ozempic and Wegovy, have funded.

[1] Semaglutide replicates 94% of normally occurring GLP-1

[2] MEN has followed me for years; it was a favorite question on the surgical boards in terms of diagnosis and treatment. It is an exceedingly rare disease, afflicting one out of 35,000 individuals – perhaps 10,000 people in the US. The only time I have seen MENs is on my surgical examinations.

Sources: FDA data

Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity NEJM DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism DOI: 10.1111/dom.14725