Dr. Henry Miller has written extensively on why it makes good sense to expedite regulatory approval by allowing our FDA to piggyback on the approvals by other countries. Today’s study flips that script and looks at how those other countries react to FDA approvals.

The researchers considered all new drugs approved by the FDA between 2017 and 2020, matching them with summary reports by “the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC), the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).” Those refused marketing authorization or not recommended for an FDA-approved indication by any of these agencies underwent a cost analysis by the researchers.

- Of the 206 FDA-approved drugs, 78.6% were approved roughly a year later by at least one of these foreign regulators.

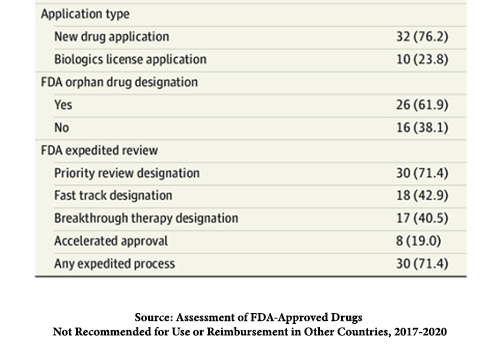

- Of the 105 reviewed by at least one agency, 42 had negative reimbursement decisions because of uncertain or small comparative clinical benefit, “comparative safety concerns, or a lack of cost-effectiveness at the proposed price.”

- Most of these drugs had orphan drug designations and were approved under the FDA expedited review pathways.

"Orphan" drugs and expedited review

The FDA has developed four expedited approval pathways to speed up the process. In no instance does this alter the required studies of safety and efficacy.

The FDA has developed four expedited approval pathways to speed up the process. In no instance does this alter the required studies of safety and efficacy.

- Fast Track – products for unmet needs or “drug or device to be superiorly effective, reduce or eliminate the side effects of available therapy, improve diagnostic accuracy, decrease toxicity, or address a public health need.” A decision on a drug application will be made within 60 days.

- Priority Review again focuses on “medicines that would improve the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of severe conditions.” It reduces the FDA review to six months.

- Breakthrough Therapy – the manufacturer requests the designation and may be applied by the FDA based on preliminary clinical evidence. It is essentially the same as a Fast Track medication, with one crucial difference. Because it is based upon preliminary clinical findings, surrogate efficacy measures, “measures that can predict or assume clinical benefit,” are allowed. These might include improved laboratory values or other biomarkers. Surrogates, hopefully, are faithful representations of the outcome of concern.

- Accelerated Approval – in many instances, benefits take years to appear. They, too, utilize surrogate endpoints, but conditional approval is granted based on those surrogates. There is a required Phase IV confirmatory trial, post-marketing, to show that the drug actually provides a clinical benefit. If no benefit is seen, the FDA can withdraw the drug.

So-called "orphan drugs" are meant to treat a "rare disease or condition” that affects less than 200,000 persons in the U.S. or where there is “no reasonable expectation” of recovering the costs of these drugs' development. These drugs receive tax credits for clinical trials, exemption from user fees, and a seven-year market exclusivity once approved. The manufacturer requests orphan drug status. Orphan drugs frequently qualify for expedited approval pathways; 40% of accelerated approvals are for orphan drugs.

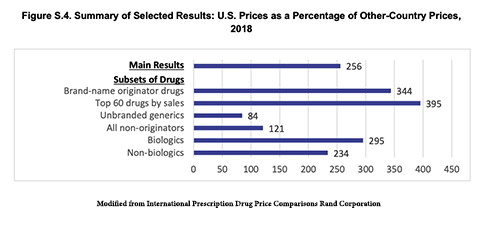

In determining where to seek marketing authorization, pharmaceutical companies have global choices. They often prioritize their requests to the FDA and its EU equivalent, the European Medical Authority, EMA – they have the largest markets. But in the U.S., we do not consider cost; as a result, the average price of therapy for drugs we approved, but other, fiscally conservative regulators did not, come to $100,000 annually. Pharmaceutical companies may well come to get approval in the U.S. first and then sweeten the deal for other countries by providing the same drug at a lower cost. The U.S. taxpayer, and we all pay taxes in one form or another foots the bill for those discounts. Part of the reason global pharma is against competitive drug pricing in the US is it will close or severely limit the piggy bank that we fund that allows them to offer other countries lower prices.

In determining where to seek marketing authorization, pharmaceutical companies have global choices. They often prioritize their requests to the FDA and its EU equivalent, the European Medical Authority, EMA – they have the largest markets. But in the U.S., we do not consider cost; as a result, the average price of therapy for drugs we approved, but other, fiscally conservative regulators did not, come to $100,000 annually. Pharmaceutical companies may well come to get approval in the U.S. first and then sweeten the deal for other countries by providing the same drug at a lower cost. The U.S. taxpayer, and we all pay taxes in one form or another foots the bill for those discounts. Part of the reason global pharma is against competitive drug pricing in the US is it will close or severely limit the piggy bank that we fund that allows them to offer other countries lower prices.

Source: Assessment of FDA-Approved Drugs Not Recommended for Use or Reimbursement in Other Countries, 2017-2020 JAMA Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6787

The Next Generation of Rare Disease Drug Policy Ensuring Both Innovation and Affordability ICER

International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons Rand Corporation