Bumble bees are prolific pollinators, vital in creating the crops we eat. A new study shows how co-evolution between the bees and the plants can reduce the deaths of bumble bees.

Plants have a hard life rooted in the ground as they are. In fight-or-flee situations, they can only fight, and as a result, they have developed several chemical and physical defenses. As it turns out, the bumble bee has latched on to a plant’s chemical defense to kill a pathogen in their gut.

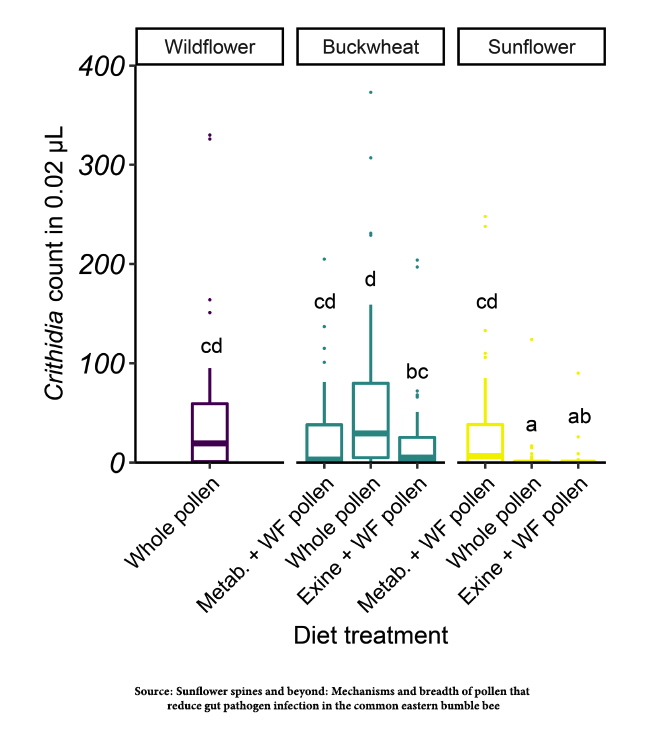

The pathogen is a global player, Crithidia bombi, a protozoan parasite of insects that reduces the “learning, survival and reproduction” of nutritionally stressed bees and over-wintering queens. The plant-based remedy is found in Sunflower pollen, although the underlying mechanism of action, physical or chemical, remains unclear. The current study sought to clarify the pollen’s activity using a strain of bees already infected with C. bombi — and fed diets differing in the types of pollen present.

The outer core of the pollen, the exine, was separated from the pollen itself and reintroduced to the treatment diets; control diets had no Sunflower pollen but did provide pollen from buckwheat and wildflowers. The amount of C. bombi was measured from the bee’s gut, researchers counted daily mortality, and measurements were made of bee wings to determine the presence of a growth slowing.

The outer core of the pollen, the exine, was separated from the pollen itself and reintroduced to the treatment diets; control diets had no Sunflower pollen but did provide pollen from buckwheat and wildflowers. The amount of C. bombi was measured from the bee’s gut, researchers counted daily mortality, and measurements were made of bee wings to determine the presence of a growth slowing.

While there was no change in mortality, sunflower pollen significantly reduced the presence of C. bombi in the gut of bumble bees. Moreover, it seemed that the outer coat, the exine, was the source of the strongest effect rather than some plant metabolic within the pollen itself. When additional testing on a pollen diet was broadened to include other Sunflower family members (e.g., dandelions and sagebrush), a similar but not necessarily as profound effect was seen on C. bombi levels.

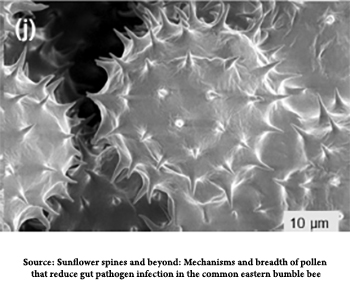

The micrograph of the sunflower exine depicts many spikes. This has left scientists in a quandary. Since the metabolites in the pollen exerted no effect, the sunflower pollen must be acting mechanically; is it “removing attached pathogen cells or preventing attachment of free-swimming cells by scraping the hindgut?”

The micrograph of the sunflower exine depicts many spikes. This has left scientists in a quandary. Since the metabolites in the pollen exerted no effect, the sunflower pollen must be acting mechanically; is it “removing attached pathogen cells or preventing attachment of free-swimming cells by scraping the hindgut?”

Bees fed an exclusive diet of sunflower pollen do not thrive; the protein content of the pollen is too low, it is not as readily digestible, and it is missing essential amino acids. As a result, sunflowers are not necessarily considered in the mix when intentionally feeding bees. Fixating on sunflower pollen’s value as a source of protein makes its value in reducing gut pathogens “invisible.” But as the authors write, “… bumble bees are generalist foragers and seldom exclusively forage on a single species.”

That should be the first of Nature’s take-home lessons – a diverse diet is more healthful because it may well contain properties that are not apparent. The discussion of the role of fiber in our diet echoes this lesson.

Nature’s second lesson is a bit more nuanced, and it has to do with co-evolution. We will never know why the coating of sunflower pollen is spiked. But from an evolutionary point of view, bumble bees with access to sunflower pollen had little survival advantage from that pollen until an enteric pathogen appeared – then the latent survival advantage of sunflower pollen came into effect. When we speak of survival of the fittest, it is not as commonly perceived as “red in tooth and claw.”

Co-evolutionary survival describes a particular niche, and fittest describes the relationship of its members to one another and to the niche itself. Despite our anthrocentric ways, we are part of a much larger niche that we co-evolved with. We should be, like the bees, generalist foragers – a healthful diet is diverse. We are, like the bees, holobionts – “a host and the many other species living in or around it,” we do contain multitudes, which leads to Nature’s third lesson. What we eat alters our microbiome, which alters our metabolism and responses; in short, we are what we eat. Do you want to be all cheeseburger and fries?

Source: Sunflower spines and beyond: Mechanisms and breadth of pollen that reduce gut pathogen infection in the common eastern bumble bee Functional Ecology DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14320