The study, conducted across 29 academic medical centers, looked at patients who were transferred to the ICU or had died 24 hours or later after hospitalization for a medical illness. The 24-hour delay was meant to eliminate those where there was not an opportunity for medical error – those not placed in the ICU due to occupancy issues and who were so ill on admission that death was more probable than not. Restricting the patients to those admitted for medical conditions eliminated patients undergoing elective surgery who might have died from operative complications. The researchers looked at 487,532 hospitalizations in calendar year 2019. 5% or 24,591 patients died or were transferred to the ICU during their hospitalization. Random selection identified approximately 100 individuals from each academic center comprising the studied cohort.

Watch the denominator!

Out of the patients who died or whose condition worsened, necessitating intensive care:

- 550 patients experience a diagnostic error. 1878 patients did not.

- 1863 patients died, 565 survived.

- 6.6% of patient deaths involved, in part, a diagnostic error. (121 deaths with associated errors/1863 total deaths)

- 22% of patients experiencing a diagnostic error died (121 deaths/ 550 patients experiencing an error)

A quick read would suggest that diagnostic errors were frequent and, in one out of five instances, lethal. However, to identify the harmful effects of mistakes, the study is “enriched,” looking solely at those who died or were transferred after admission. These study results use the enriched group, the 24,591 patients, as the denominator.

When instead we consider the entire hospitalized population, the 487,532 patients as the denominator, a significant diagnostic error occurred in 0.3%. [1] It's a less frightening statistic. None of these deaths is acceptable, and we can and should do better, but the choice of denominator makes a significant difference.

Post-admission transfers indicate a worsening condition, but that may be due to the disease itself or the failure of therapy, two conditions not considered by the researchers, and neither a diagnostic error. This ambiguity of cause immediately introduces uncertainty. That said, it remains critical to note that diagnostic errors in acute medical care can result in significant harm.

What errors were made?

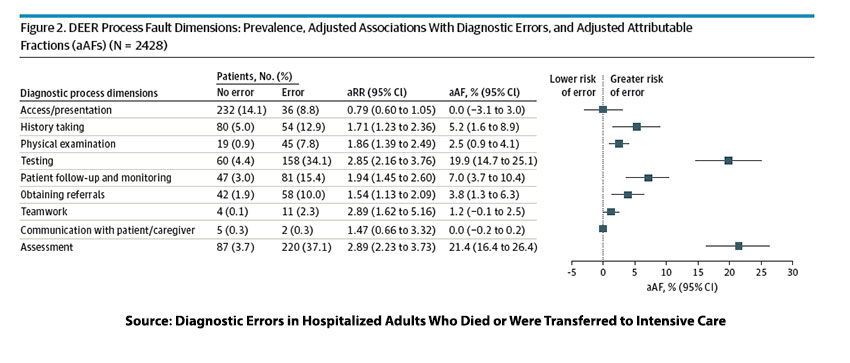

The table displays the various categories of diagnostic errors. Let’s begin with the good news: accessing care and communications with patients and other healthcare “team” members were rarely sources of error. The problem lies in three entangled areas. Diagnostic errors were made in:

- Assessment, having the wrong working diagnosis. A single or even multiple working diagnoses guide initial care. While the researchers separate it, assessment includes good history taking and physical examination. The history and physical act as a dialogue for the physician supporting, suggesting, contradicting, or ruling out a diagnostic list that prioritizes treatment. [2]

- Testing - Generally, our initial assessment influences our testing to prove or disprove our working diagnosis. The initial testing is a “shotgun” approach designed to provide the “big picture.” Errors occur when the testing is either not broad enough to serendipitously goad the clinicians towards the correct working diagnosis or was incorrectly interpreted.

- Patient follow-up and monitoring – Unlike the previous errors of thought, this is an error of inattention, allowing the “true” underlying condition to “fall between the cracks.”

In the last column of the table, the researchers present their calculation of how much of the error was attributable to that specific factor. These three factors account for 48% of the underlying errors. If we were to add history and physical as part of assessment, it would explain 55% of the source of errors.

Unfortunately, only the inattention within patient follow-up and monitoring, 7% of errors, can be addressed with reminders, to-do's, and checklists. Improving our cognitive skills to broaden our diagnostic considerations and testing is difficult to achieve and costly. (I am not arguing over the value of human life, simply stating that more testing, at more cost, does not necessarily improve outcomes)

Much of our training, captured in those pithy sayings (heuristics), tells us to be parsimonious in our thinking – “When you hear the sound of hooves, you do not think of Zebras.” While we nearly always stumble to the correct diagnosis sooner or later, we must think more like TV’s Dr. House [3] or Sherlock Holmes to broaden our thinking in a timely manner.

Gregory (Scotland Yard detective): “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Sherlock Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

Sherlock Holmes: “That was the curious incident.”

– The Silver Blaze

The dog failed to bark because he knew the perpetrator. Recognizing the piece that “does not quite fit” is artful skill and experience. Both are hard to learn and even more difficult to teach.

[1] 6.6% of the study group died, in part, from diagnostic errors. This statistic came from the 5% of patients dying in the cohort. With extrapolation, 0.06 x 0.05 = 0.003 or 0.3% of the total

[2] Artful physical examination has been in decline for decades, often because CT imaging provides more quantifiable information than our older ways. But in some cases, a well-performed exam will provide a more nuanced consideration in addition to the caring “laying on of hands.”

[3] Dr. House is a diagnostician who “often clashes with his fellow physicians, including his own diagnostic team, because many of his hypotheses about patients' illnesses are based on subtle or controversial insights.”

Source: Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Adults Who Died Or Were Transferred to Intensive Care JAMA Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7347