Who is the most widely known military leader in history? Patton? Napoleon? Washington? There are plenty of choices but in my opinion, it has to be General Tso, hands down. As of 2023, there were 24,128 Chinese restaurants in the U.S. and you'll have to look long and hard to find a single menu that doesn't list General Tso's Chicken as an entry, usually with a little pepper icon next to indicating hot. Assuming (wild guess) that 50 people per day open one of these menus, the General has a potential exposure of 440,336,000 views per year. He's a serious influencer!

Why should anyone care about any of this?

There are plenty of reasons, spanning a variety of disparate subjects: History, evolution, biology, chemistry, and the culinary arts. Read this article and you'll be supernaturally prepared should you ever find yourself in this (admittedly unlikely) position:

Who was General Tso?

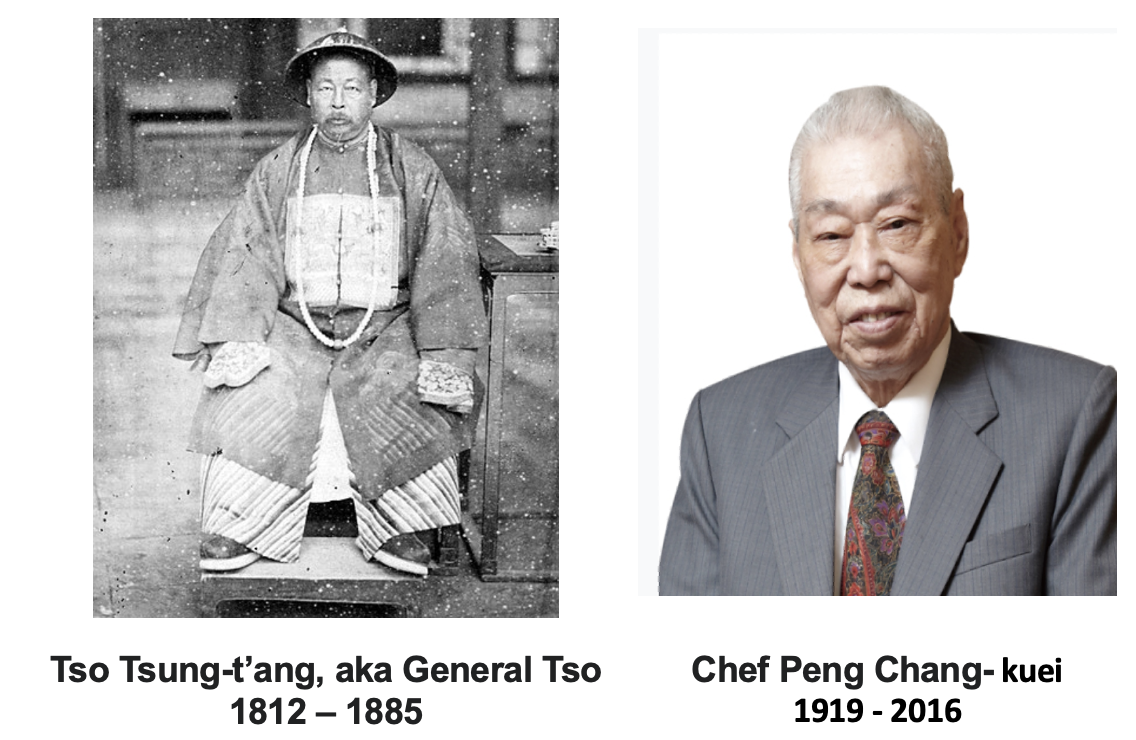

There actually was such a person (1). But he has almost nothing to do with the sweet and spicy dish with an orange flavor enjoyed by so many of us. According to Military.com, General Tso's chicken was created in 1955 by Peng Chang-kuei, a chef originally from China's Hunan Province. Hunan food is known for its spiciness; this is the only real connection between the General and the dish, which isn't real Chinese food, but rather, "Chinese-inspired" food adapted for American tastes.

(Left) The General doesn't look much like a warrior or a cook. (Right) Chef Peng Chang-kuei, the chef who immortalized General Tso. Both photographs: Wikipedia

What makes spicy foods hot?

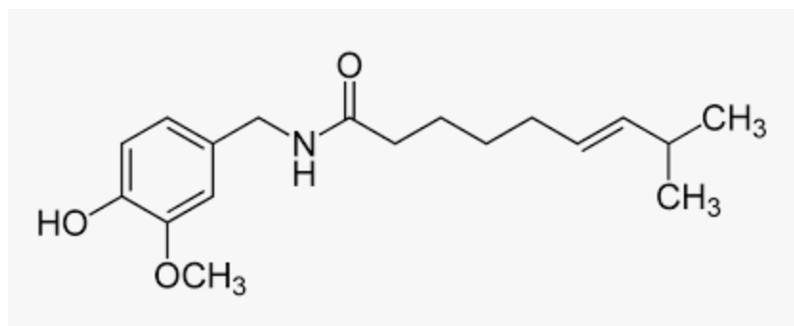

Most of you already know that chili peppers, specifically capsaicin, the active chemical in them, are responsible for whatever havoc the damn things wreak on your mouth.

The chemical structure of capsaicin. Looks innocuous enough. Nope.

Why is capsaicin "hot"?

Technically, it's not. A pepper or bottle of capsaicin is the same temperature as everything around it. But try telling that to the red-faced dope in the next booth who accidentally chomped down on a chili pepper while piggishly scavenging around for the last morsel of chicken and now feels like he swallowed a bag of molten ball bearings. (2)

A delicious serving of the General's uber-popular dish. But beware of hidden pieces of chili pepper. They can blend in, as shown by the black circle of doom. Photo: Flickr

Such a reaction to a chemical substance is rare. Of the 20 million known organic chemicals only a handful are perceived as hot. This is no accident; it's a great example of evolution. Twice.

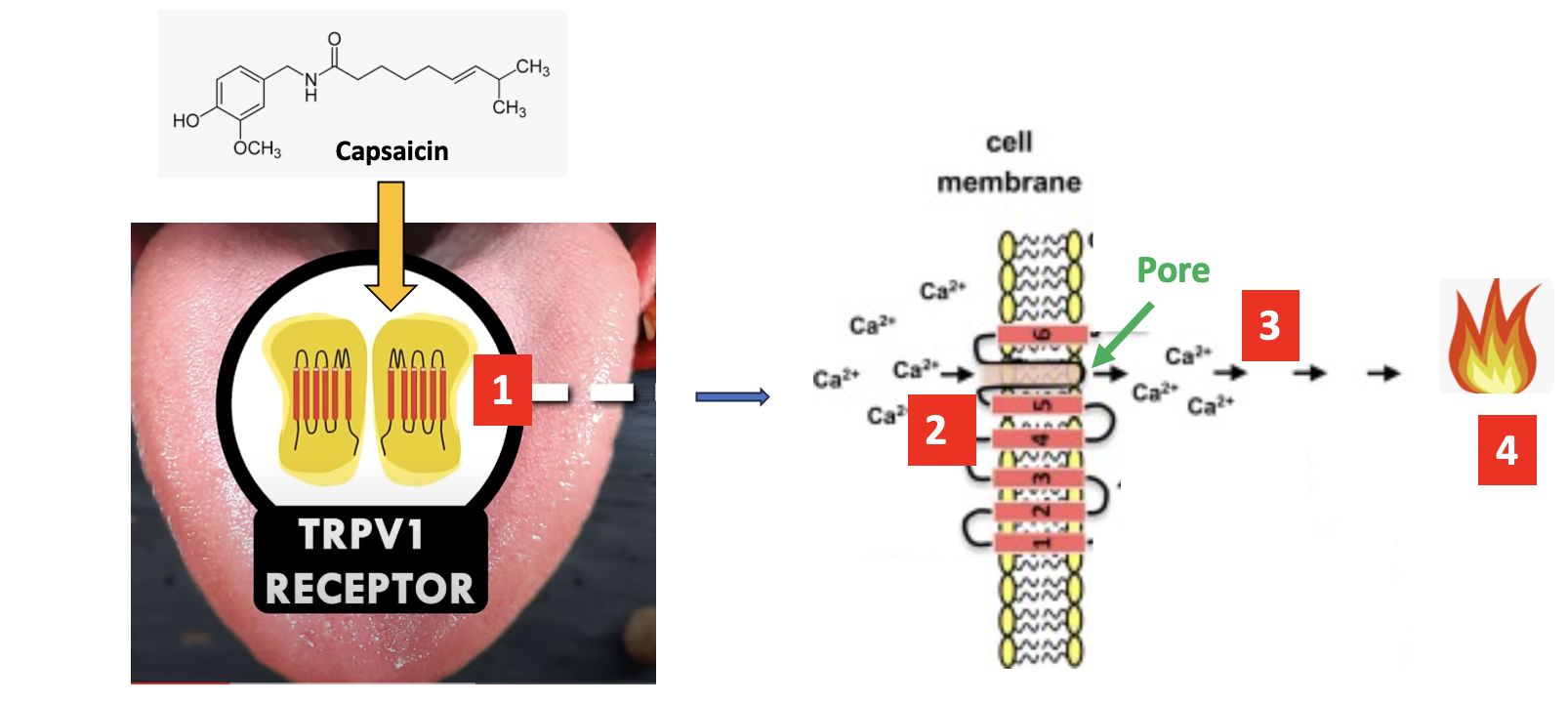

On the tongue is a receptor called TRPV1 (transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 vanilloid receptors, if you prefer, See Figure 1). TRPV1 belongs to a family of thermoreceptors that "trigger" when exposed to high temperatures (~ 110oF and above). Heat promotes the opening of pores in the TRPV1 receptor membrane, which increases the flow of calcium ions into neurons – the beginning of a signal that after several sequential biochemical steps is ultimately interpreted by the brain as pain. The obvious function of these receptors is preventing or minimizing tissue damage from the heat source, much like any pain receptor.

Why does capsaicin act like heat?

TRPV1 is also called a capsaicin receptor, meaning that the tongue "perceives" the chemical as heat. The reason for this is not obvious unless you know the science. These seemingly unrelated stimuli are another example of evolution, this time by plants. As a protective mechanism, plants like hot peppers evolved so that they were able to biosynthesize capsaicin to prevent animals from munching on them. Like humans, other mammals also have TRPV1, so a plant that "learns" how to make a chemical that is perceived as hot will not be eaten by animals, giving it an advantage over plants that do not.

In other words, the TRPV1 receptors were already built into the mouths of mammals and the plants responded – a typical co-evolutionary sequence, which is seen in many different forms (e.g. plants making their own insecticides) throughout the plant kingdom.

Figure 1. A simplified diagram of the effect of capsaicin. [1] Capsaicin binds to TRPV1 on the tongue. [2] This causes the opening of a pore (green arrow) in the cell membrane allowing calcium ions to flow into neurons [3]. The calcium ion signal, after several intermediate steps, is interpreted by the brain as heat/pain [4]. Credits: YouTube, Journal of Biochemical Pharmacology

A little chemistry

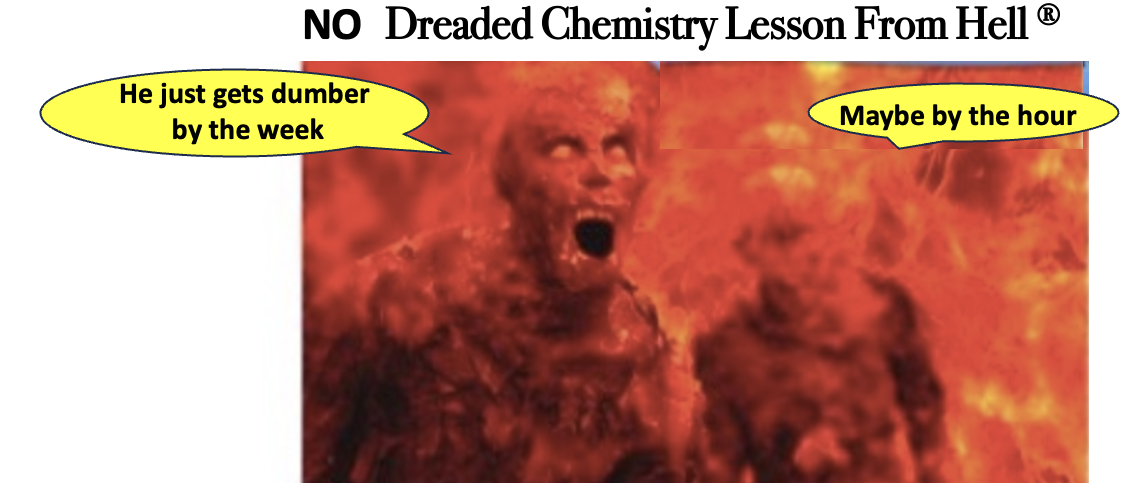

Sorry, fans. No DCLFH® today. When I asked Steve and Irving to host a lesson about heat they laughed in my face, saying it was too cold for them. They can go to hell.

Steve (left) and Irving outright refused to perform their jobs as hosts of the DCLFH®. Then again, they haven't reached their current station in life by being exemplary role models.

Today's chemistry lesson will be in the form of a quiz. <------ (Ha ha! Reader losers!) Don't screw this up or you'll find capfuls of capsaicin in your toothpaste.

Quiz:

1. Part of the name of TRPV1 includes the word "vanilloid." Why?

2. If you overindulge in capsaicin and want to rinse it out of your mouth don't drink water, drink milk. Why?

Answers:

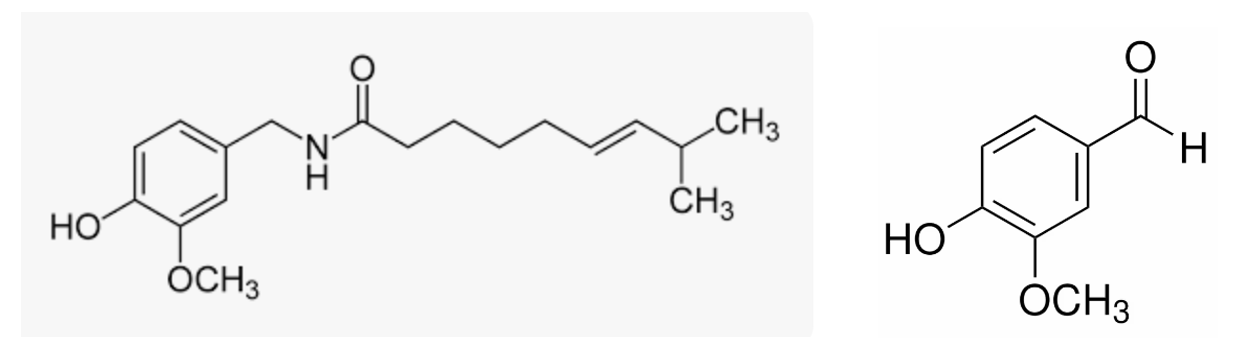

1. If "vanilloid" sounds like it has something to do with vanilla, it does. Note the similarity between the chemical structures of capsaicin (left) and vanillin (right) -- the chemical that gives vanilla its flavor.

2. Capsacin is highly lipophilic (fat-loving). It will dissolve in gasoline or oil but not water. But milk has globs of fat that are emulsified into the liquid. The fat will help dissolve the capsaicin.

It's dinnertime, so let's end this. I have a big order of General Tso's waiting at Hunan Village down the road. I don't have any milk to cope with a capsaicin meltdown but ice cream works as well and a trip to Carvel is also on the agenda. Bon appétit!

NOTES:

(1) I discovered that there were two General Tsos but opted to only cover Tso Tsung-t’ang. The other one was nothing special, sort of Tso Tso.

(2) There is a dose-response involved. If you eat peppers without much capsaicin you will probably survive. This depends upon what breed of pepper is used. Chili peppers range from "not too bad" to "Chernobyl mouth" depending on the amount of capsaicin in the particular breed.

P.S. My most esteemed colleague Dr Henry Miller wondered whether my menu calculations above were correct because I may have not taken into account General Tso's Vegan Chicken! Could this really move the needle? So, I did a literature search of General Tso's Vegan Chicken but this is all I found:

Jennifer was part of a focus group that was asked to opine on the merits of General Tso's Vegan Chicken. Unfortunately, this involved tasting it first. Ten of the 12 members of the group reacted similarly. The other two died of natural causes. Photo: Flickr