“Such is the character of human language, that no word conveys to the mind, in all situations, one single definite idea . . . .” Chief Justice Marshall

In social interactions, including those of the Court, the ambiguity of language allows one to bridge the gap between the penalties of outright disobedience and doing as one pleases. Following the letter rather than the spirit of the law is often the refuge of scoundrels. Former Congressman George Santos comes to mind in this wordplay,

"I am Catholic. Because I learned my maternal family had a Jewish background, I said I was 'Jew-ish'"

Research has suggested that adults use these linguistic gymnastics to avoid conflict with peers or, the more powerful, charting a middle path between non-compliance and punishment. The continuing vaccination debate emphasizes that cooperation is often the key to success (herd immunity) but isn’t always aligned with our personal goals. Social reasoning involves assessing our and other’s needs and prioritizing our actions.

Sometimes, after the terrible twos, when non-compliance with parental desires is first vocally and physically demonstrated, our children discover this verbal workaround of parental control, allowing them to balance their needs with their parents. A new study tries to gauge when a child learns these linguistic “loopholes.”

Sometimes, after the terrible twos, when non-compliance with parental desires is first vocally and physically demonstrated, our children discover this verbal workaround of parental control, allowing them to balance their needs with their parents. A new study tries to gauge when a child learns these linguistic “loopholes.”

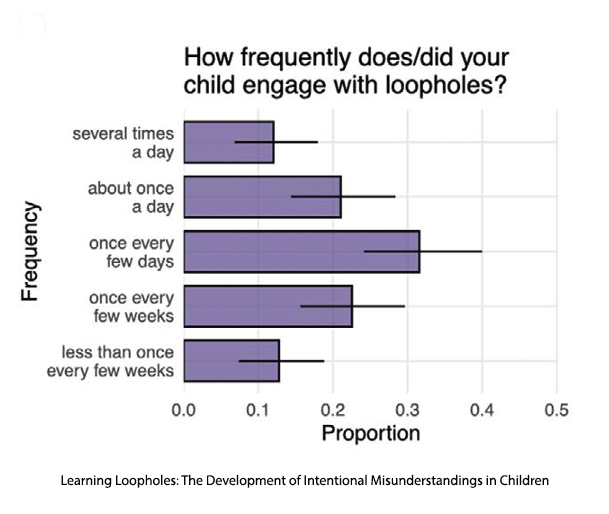

The researchers began by asking 260 parents of 425 children aged 3 to 18 whether they had noted “loophole behavior” previously or currently in their children. This was a common occurrence. 60% of children had exhibited this behavior with a trajectory that began between 4 and 6, peaked, and became less frequent between 6 and 12. The researchers also categorized the “domains” involving loopholes that included:

- Play

- Eating

- Household rules

- Safety

- Bedtime

- Social interactions

Unsurprisingly, play, especially putting down screens and eating, involving circumventing restrictions on sweets, were the most common at nearly 30% each. Having demonstrated that children do indeed use loopholes, they went on to examine what the rugrats were up to.

In a series of experiments, children aged 4 to 9 listened to stories based on the examples provided by the parents where a child responds to a parental “directive” by complying, not complying, or finding that linguistic loophole. In the first series, 108 children, on average age 7, were asked how much trouble the child protagonist would get into for their behavior. They found that children “evaluated loopholes as leading to more trouble than compliance, and less trouble than non-compliance.” They also found that children, based upon their outward emotional response, found loopholes “funnier than either compliance or non-compliance, providing further evidence that they distinguish loopholes from both of these behaviors.” – parenthetically, this is just how adults view these loopholes.

In the next series, children heard these scenarios and were told whether the child protagonist agreed or disagreed with the parental directive. The children were then asked to predict the protagonist’s response. 90% of the time, the participants favored compliance when parental and child goals were aligned; unfortunately, that compliance dropped by half, to 46% with misalignment, and was evenly split by loopholes or non-compliance. There is some good parental news, loophole use peaked at ages 7-8, as older children reckoned loopholes were equally punishable as non-compliance.

In the final series, children were given the same scenarios and asked how the child protagonist could be “a little tricky or sneaky” without getting into too much trouble. [1] As might be expected, children could generate these loopholes, again with the same trajectory, “At five, they favored non-compliance over loopholes, but by eight, this pattern reversed.”

“Loopholes allow people to avoid compliance while minimizing the consequences of outright defiance, a strategy particularly useful for children navigating power imbalances with adults.”

One of the interesting questions raised by the study is why there is a rise and fall in behavior. The researchers suggest that young children see the loophole as “plausible deniability” and that, with further experience, they recognize the strategy is less effective because punishment still follows or may become worse as they “frustrate” their parents. They also suggest that humor plays a role, that parents find the linguistic wordplay cute and amusing early on, but the threshold changes with time, “making loopholes less socially acceptable in parent-child interactions.

Chief Justice Marshall's observation on the slipperiness of language finds its echoes in every facet of human interaction—from toddlers testing their parents’ patience to adults crafting statements that dance on the edge of truth. The study’s findings suggest that linguistic loopholes are an early developing, naturally occurring behavior that peaks in childhood but never truly disappears. Instead, it matures into the verbal acrobatics of politics, law, and public health debates.

Consider the discourse over-vaccination. Social reasoning—the very skill that children fine-tune through loophole play allows private and public officials to say, “I’m not “anti-vaccine,” I just believe in natural immunity.” or “I’m not against public health measures, but personal choice is paramount.” Less outright defiance, more strategic sidestepping. Congress, too, seems perpetually stuck in the loophole-loving age of 7 to 8. We’ve seen the same tactics play out in legislative behavior, where language is parsed to thread the needle between appearing to take action and actually doing so.

As this study shows, children eventually learn that loopholes lose their charm when consequences catch up. Perhaps the same reckoning awaits those who twist words to avoid accountability—whether dodging bedtime or responsibility. Until then, expect more artful dodging, more plausible deniability, and more variations of “I never said I wouldn’t not do it.”

[1] “For example, if told to eat peas before more pizza, one child might openly refuse, while another might secretly discard the peas when the parent isn’t looking.”

Source: Learning Loopholes: The Development of Intentional Misunderstandings in Children Child Development DOI:10.1111/cdev.14222