When a Calling Collides With Reality

I suspect that if one were to read medical school admission essays, they would all include some language describing medicine as a “calling.” Not merely a job, but a role imbued with moral, personal, and social significance. In recent years, much has been written within medicine about rising burnout when that deeply meaningful ideal collides with the realities of modern, corporatized healthcare. Rather than piling more blame onto healthcare systems, a new paper takes an unexpected detour, using Santa, to illuminate why callings sometimes exhaust rather than sustain.

Researchers writing in a management journal carried out interviews with professional Santas (see below) and were struck by how many described their work as a calling—much like medical students and physicians—and had actively organized their lives around it. Prior sociological research suggests that living out a calling depends not only on passion but on believing you can perform the role and being validated by others. For Santas, that validation hinges on how closely one matches the cultural image of “Santa.” Those who look and act the part are embraced by peers and audiences and treated as ideal occupants of the role. Not everyone, however, fits that narrow stereotype—traditionally imagined as white, male, bearded, Christian, and perpetually jolly. Those who diverge risk being seen as less legitimate, thereby complicating their ability to fully enact their calling.

This observation led the researchers to a central question: how does prototypicality shape whether—and how—people can follow their calling?

Inside the World of Professional Santas

There are roughly 1,000 members of the U.S. Fraternal Order of Real Bearded Santas, along with 6,700 in the Worldwide Santa Claus Network. Santas are independent contractors who perform largely seasonal work, though some pros work year-round. Like other independents, they find jobs through online advertising, referrals, and partnerships, work that comes with set structural and cultural expectations. All of the professional Santas experienced work as a calling, providing love, hope, and joy to their community. As the researchers note, “meaning within Santa work was derived through value provided to others or spiritual means.”

Using surveys, interviews, and workshop observations, the researchers collected data from over 1,000 professional Santas and identified three broad identity patterns.

- Prototypical Santas, the “naturals,” physically and behaviorally aligned with the societally expected Santa, start from a sense of confidence, making it easy to slip into and actively maintain the Santa persona. That identity becomes strong and durable: they see themselves reflected in the role, identify intensely as Santa, and carry that identity beyond the job, blurring the boundary between “Santa at work” and “me at home.” Living as Santa becomes less a scheduled performance and more a way of being, realizing a “high role identification that enabled continuous calling enactment.”

- Semi-prototypical Santas, the ones we might say “fake it till they make it,” deviate from the cultural stereotype in ways the community tolerates. Despite sitting in Santa’s chair and hearing children call out “Santa!”, they often feel like impostors. To manage this discomfort, they reconcile their doubts in two ways: by crafting narratives that legitimize their differences (for example, a skinny Santa describing himself as “a healthy Santa—my doctor likes me this way”), or by actively managing their appearance and behavior to better match expectations. These Santas have lower role identification. They portray Santa rather than being Santa around the clock, separating work from nonwork and living their calling in episodes rather than continuously.

- Non-prototypical Santas, with physical or behavioral differences not accepted by the Santa community, are more discordant than impostors and reframe themselves as trailblazers, challenging assumptions about who Santa “is for” or what Santa “must be,” and emphasizing broader, more inclusive meanings of the role. This additional cognitive work paradoxically produces the same sustained, high role identification seen in prototypical Santas. Despite barriers and rejection, they too become Santas around the clock.

Role salience describes how much priority one role holds over others. In my own life, those roles include surgeon, husband, dad, brother, son, and friend. High role salience characterizes both prototypical and non-prototypical Santas. The researchers suggest, however, that an episodic calling—lived intensely but not continuously—may be healthier, allowing for better work–life balance. This raises an obvious question: how much might these Santa findings illuminate an underexplored source of physician burnout? After all, both professions are framed as callings.

Why This Makes Doctors Uncomfortable

If Santa offers a mirror for medicine, generational conflict may explain why that reflection feels so uncomfortable.

“Kids!

I don't know what's wrong with these kids today!

Why can't they be like we were

Perfect in every way?

- Bye Bye Birdie

Generations and the Problem of ‘Commitment’

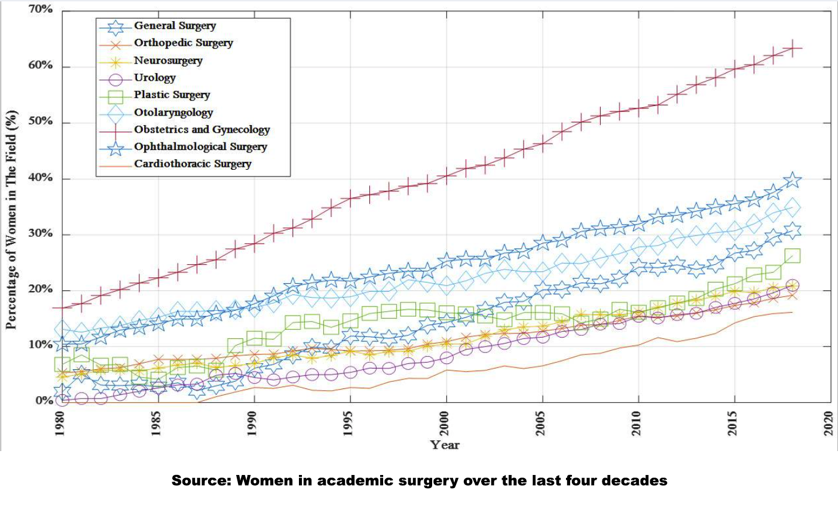

Many of my Boomer physician colleagues feel that younger doctors are preoccupied with work–life balance. Younger physicians also report higher burnout—a term rarely used during my training, when “a call for help” was seen as weakness—and are perceived as less willing to place work ahead of home. But what if something else is happening? Could the growing diversity of medical students and their entry into previously exclusionary specialties reflect a rise in semi-prototypical and non-prototypical physicians? Surgical fields have seen meaningful, though uneven, gains in gender equity, and a Canadian study found that women were twice as likely as men to leave general surgery training. These patterns may reflect not a waning commitment but a misalignment between people and entrenched professional prototypes.

Many of my Boomer physician colleagues feel that younger doctors are preoccupied with work–life balance. Younger physicians also report higher burnout—a term rarely used during my training, when “a call for help” was seen as weakness—and are perceived as less willing to place work ahead of home. But what if something else is happening? Could the growing diversity of medical students and their entry into previously exclusionary specialties reflect a rise in semi-prototypical and non-prototypical physicians? Surgical fields have seen meaningful, though uneven, gains in gender equity, and a Canadian study found that women were twice as likely as men to leave general surgery training. These patterns may reflect not a waning commitment but a misalignment between people and entrenched professional prototypes.

Medicine’s Prototype

The Santa research is ultimately about identity fit—not whether people feel called, but how that calling is lived. Medicine, and especially surgery, has a robust and culturally reinforced prototype. Though less consistent than in the past, training norms still often favor total availability, emotional stoicism, and an identity tightly fused to the role. I still describe myself, first and foremost, as a surgeon.

In the Santa framework, that’s prototypical Santa, a strong template that signals legitimacy. Many of us trained and practiced in a system that rewarded that surgical stereotype because it met the demands of the time. As a result, when we see younger physicians mention, let alone protect, home time, we interpret it as less tough, committed, and professional.

Santa offers a different lens, telling us that the calling remains, but because they reject, and often rightly so, some of our Boomer ways and stereotypes, they are more semi-prototypical Santas – caught in an imposter-ish dissonance between what was and what is. Medicine remains a calling, but at the time and place of their choosing, there is no need to be 24-7.

Burnout then becomes not just “too much work,” but too much identity friction where the role’s demands are huge, the validation is thinner, the metrics are louder, and the safest way to survive is to keep medicine meaningful in episodes rather than letting it colonize the whole self.

The lesson from Santa is not that devotion has waned, but that devotion no longer looks the same. Burnout emerges when medicine demands a single, totalizing prototype—one that rewards constant availability, emotional austerity, and identity fusion—while the profession itself grows more diverse in bodies, values, and lives. Younger physicians are not rejecting the calling; they are renegotiating it, choosing episodic meaning over perpetual self-erasure. If medicine can learn from Santa, it may discover that preserving joy, purpose, and longevity requires loosening the costume—allowing doctors to serve wholeheartedly without having to be Santa or a surgeon twenty-four hours a day.