There are about 46,000 organ transplants performed a year in the US; their success is, in considerable measure, due to the pioneering work of Gertrude Elion. So, too, are we indebted to this remarkable woman for medications used to treat leukemia, malaria, cancer, and infections such as meningitis and sepsis? With grit, determination, stubbornness, and relentless effort substituting for a PhD, Gertrude Elion’s work transcends the seven crucial pharmaceuticals she discovered alone or in partnership with Dr. George Hitchings. Gertrude and George revolutionized the way drugs are created - serving as the foundational methodology for drug discoveries performed today.

Born in 1918 to Eastern European Jewish parents, Gertrude, “Trudy” spent her formative years in the Bronx. She distinguished  herself as a student early on, crediting her stubbornness, perseverance in the face of nay-sayers, and insatiable quest for knowledge for her achievements. Gertrude’s father, a dentist, had achieved some measure of wealth, losing everything in the Depression, forcing him into bankruptcy. But, with his education and practice intact, the family weathered the crisis. The financial crash seemed to have little effect on the young Gertrude, who was far more influenced by the death of her grandfather from stomach cancer when she was 15 (her mother died a year later), driving her to find a cure, eschewing her father’s nudges to follow in his footsteps into dentistry, and fulfilling her mother’s wish for her to have a career.

herself as a student early on, crediting her stubbornness, perseverance in the face of nay-sayers, and insatiable quest for knowledge for her achievements. Gertrude’s father, a dentist, had achieved some measure of wealth, losing everything in the Depression, forcing him into bankruptcy. But, with his education and practice intact, the family weathered the crisis. The financial crash seemed to have little effect on the young Gertrude, who was far more influenced by the death of her grandfather from stomach cancer when she was 15 (her mother died a year later), driving her to find a cure, eschewing her father’s nudges to follow in his footsteps into dentistry, and fulfilling her mother’s wish for her to have a career.

After a distinguished tenure at Hunter College and earning a Master’s degree in Chemistry at NYU in 1941 (she rejected biology because she didn’t want to do dissections), Gertrude had a formidable job finding a suitable position to showcase her talents and education. Like many female science students of her day, women were relegated to teaching or nursing, and she was lucky to begin her career as a technician at A&P - measuring acidity and contamination in foods (after first teaching chemistry and then being a secretary). But it wasn’t her first love – which was doing research.

That took more years of perseverance, unpaid work, and several painful rejections (including one for being too attractive and a distraction for the men). Her felicitous association with Dr. Hitchings and ensuing research work came from a chance encounter with a bottle of pills in 1944. She purchased a bottle of aspirin at a local pharmacy and noticed it was manufactured by Burrough’s Welcome (now GSK). On a whim, she contacted the company and asked if they had any laboratory openings. They did -- and the rest is the subject of the biography of a Nobel Prize winner.

The Pioneering Methodology

Gertrude began her work with straightforward research into the uncharted world of nucleic acid biosynthesis and its associated enzymes, focusing on the purine molecule, a critical component of DNA. However, her contribution to science and ensuing drug discoveries went far beyond that. At the time, drug research involved an ad hoc trial and error approach, throwing different chemicals at a pathogen and seeing what happened. Gertrude and George took the prevailing methodology and stood it on its head.

“Understanding that all cells require nucleic acid to reproduce, they reasoned that rapidly growing bacteria and tumours require even more to sustain the pace of growth. Find a way to disrupt their lifecycle, and you find a way to stop disease.”

Instead of tweaking a potential drug's chemical structure, they focused on understanding the pathogens involved in a particular disease, crafting the drug to target the pathogen’s weaknesses. Their revolutionary approach examined the biochemical differences between healthy human cells and cancer cells, bacteria, and viruses, identifying how nucleic acids are metabolized differently in each. Using that approach, they synthesized antagonists or blockers to nucleic acid derivatives in the pathogens, tricking them into accepting the lethal drugs as part of their biological pathway. These agents killed or blocked cancerous cells from replicating while leaving healthy cells intact.

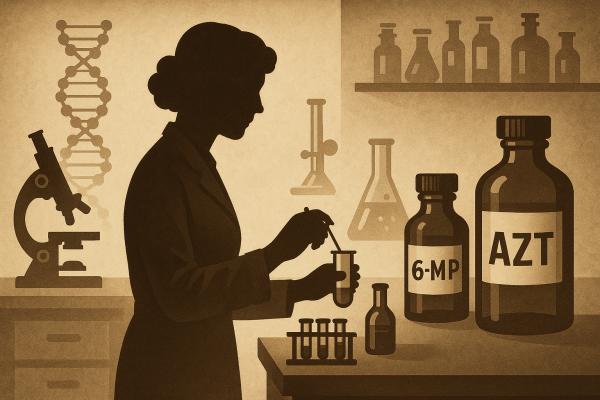

Using this method, Gertrude’s first success came in 1950, with 6-mercaptopurine, used to treat leukemia, at least temporarily enabling her to fulfill her childhood dream of combatting cancer. In 1957, she discovered another purine, azathioprine or Imuran, an immuno-suppressive agent that facilitates organ transplants. By blocking the body’s normal reaction of immunologically attacking all objects the body identifies as “foreign” or non-self, including transplanted tissues or organs,” the normal host-graft reaction which typically resulted in organ rejection and failure could be avoided.

The new methodology called“Rational Drug Design,” for which Gertrude and George co-won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1988, produced other crucial drugs, including acyclovir, an antiviral, used to treat infections caused by the herpes simplex virus and the varicella-zoster virus. Understanding the drug’s mechanism overturned the prevailing wisdom of the day, which believed that creating effective and selective antiviral agents was impossible. The new methodology also enabled Gertrude’s students to discover the therapeutic potential of AZT, a discarded anti-cancer drug, to treat AIDs.

The Hero’s Dilemma

Like all heroes, Gertrude had her trials. When she first began working at Burroughs Welcome, she decided she needed a doctorate to advance, enrolling at Brooklyn Polytech for her PhD and a two-hour commute from the company’s headquarters in upstate NY to Brooklyn for class. While this might demonstrate extreme commitment to some, Polytech’s dean felt otherwise, requiring Gertrude to choose between her job and a PhD. She chose the former (which she loved). Luckily, she didn’t live to regret her choice. In addition to her Nobel, over her career, Gertrude registered 45 pharmaceutical patents and was awarded 25 honorary degrees and doctorates, including being named to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1991 and becoming the head of the Department of Experimental Therapy(which she had created) at Glaxo SimithKline, the successor to Burroughs Wellcome.

Upon retirement from Burroughs Welcome in 1983, which had relocated to North Carolina in 1970, Gertrude began her second career as an academic at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where she became an adjunct professor, and at Duke University, where she became Research Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology with a memorial award for first-year medical students established in her honor.

The final lines of her bio on the Nobel website might be the most fitting to describe Gertrude Elion’s accomplishments.

“Simply put, Elion changed the way researchers develop drugs. As a result, although she died in 1999 at the age of 81, Gertrude Elion is still saving lives.”

“How you handle setbacks can make a difference. In science, you have to take several approaches to setbacks. You have to say to yourself that you’ve tried everything, it didn’t work, so I have to go in a different direction….You must never feel that you have failed. You can always come back to something later, when you have more knowledge or better equipment and try again.”

– Gertrude Elion [1]

Sources Gertrude B.Elion Nobel Prize Organization

A Biography of Gertrude B. Elion

Gertrude Elion, Master Chemist Stephanie St. Pierre

Image of Dr. Elion courtesy of GlaxoSmithKline plc - GSK Heritage Archives, Creative Commons on Wikipedia