Here’s the title of a new article from CBS News:

"If these items are in your medicine cabinet, it's time to throw them away. Here's how to do it safely."

In which they offer the following advice:

“Here's your friendly reminder not to overlook your medicine cabinet in your cleaning routine.”

And here's a perennial message from the FDA:

"Don’t Be Tempted to Use Expired Medicines...Out with the old! Be it the fresh start of a new year or a spring cleaning, consumers are encouraged to take stock of what has surpassed its usefulness. Medicines are no exception."

Both of them should STFU.

Every spring, Americans are told to toss expired medications with cheery reminders from the FDA and media alike. But behind that advice lies a blend of misinformation, bad science, and callous indifference, especially prescription opioids, to those living with pain.

FYI, the FDA's National Prescription Drug Take Back Day occurred last month. I guess I missed it. If you're lucky, you did too.

Let's call out some BS

This advice is a load of crap.

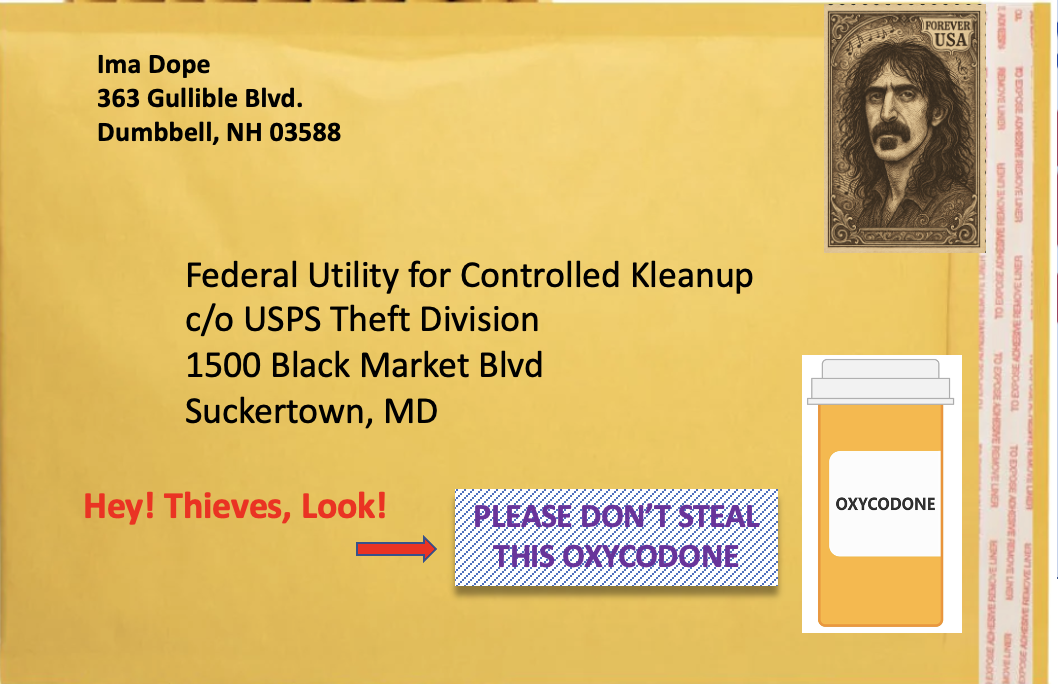

In a perfect world, the FDA's advice might be OK, but if you are one of millions of people who live in pain, the agency has zero credibility here; especially because it created a monumentally dumb program where people with "excess" opioids can put them in an envelope and mail them back to the FDA. What a splendid idea!

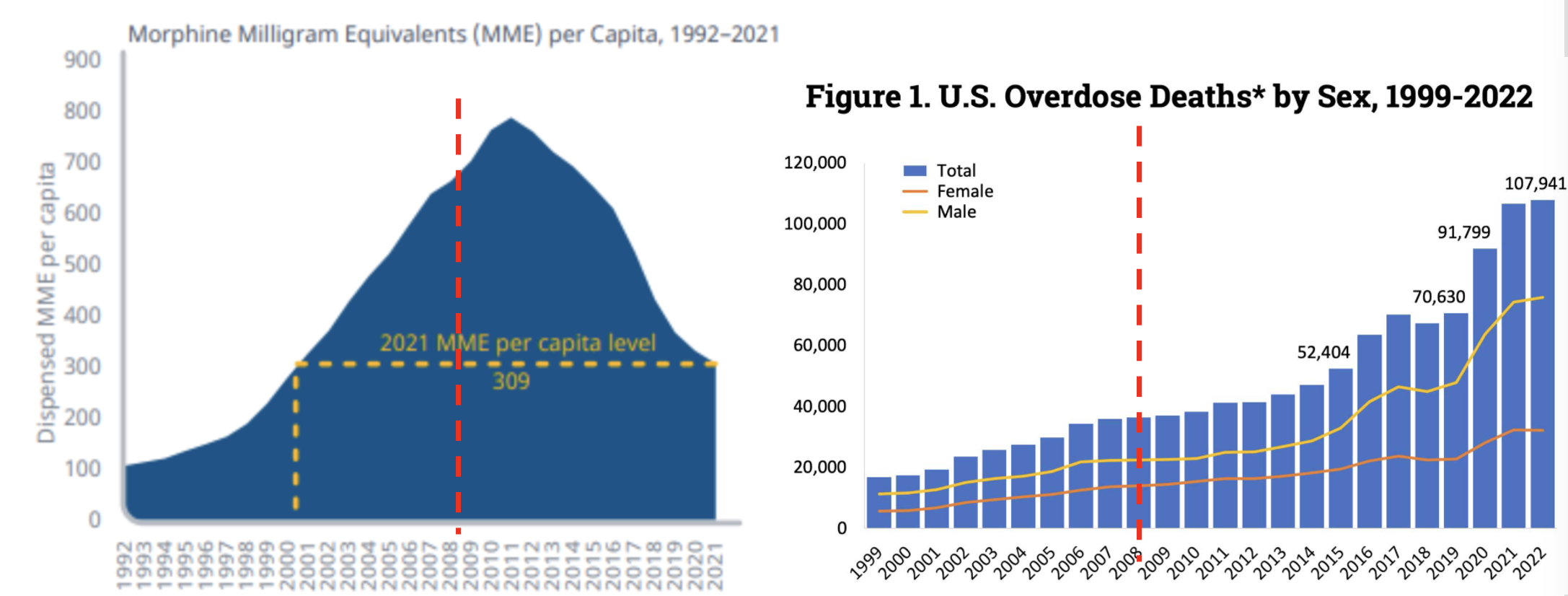

Where might those "excess" pills come from? How about "nowhere?" Thanks to miscreants like members of PROP [1], this concept is laughable. But, it isn't so funny if you're one those people who are coping with anti-opioid mania and know that the chances of getting replacement pills back are about the same as a dung beetle solving the quadratic formula. You already know that there aren't too many pills "in circulation;" there are too few. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Excess pills? Really? Between 2008 and 2021 opioids prescriptions have been slashed radically while at the same time opioid overdose deaths more than tripled. In case you haven’t figured it out, the real story that it's street drugs — primarily illicit fentanyl — that are driving these deaths. Sources. Pain News Network, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

If you want to dispose of or return your unused opioids feel free to do so, but doesn't that seem a bit like returning the unused portion of your paycheck to your employer? "Well boss, I didn't need all of my salary this month, so here's what I didn't use."

And here's what I envision the return envelope might look like:

Speaking of the drugs being stolen, when I first wrote about this, a reader who calls himself Victor Frankenstein (presumably a pseudonym, but I can't be certain) left a comment. It's pure gold.

"I had mentioned this to a good friend over a couple of beers, who is also a U S Postal Service Employee. After his beer shot out of his nose, we were able to clear his airways and get a proper response. He noted that the U S Postal Workers will ensure that any of these envelopes "clearly marked" will be properly and expeditiously delivered to the proper receiving entity. Not.

On another note: Years ago, he also informed me that a good U S Postal Service Worker can smell money in an envelope and also showed me how to remove it from the envelope without opening it. Using only a "Hair Pin"... I have a question. Is it not illegal to send narcotics through the mail? Unless of course, it's from China."

Victor Frankenstein in rare form.

Way to go, Vic!

Note: What follows is my opinion, which is based on 25 years of experience with the chemistry and metabolism of drugs. I spent an entire career learning how stable (or unstable) compounds are.

I'm not encouraging anyone to take any medicine after the expiration date on the bottle. This article is merely a look at the data on drug efficacy and safety over time. You can decide for yourself what, if anything, to do with this information.

Medscape thoroughly trashes the FDA's advice.

"Note that the FDA requirement is a date at which potency is still guaranteed. In most cases, the drug in question has not been tested for efficacy or toxicity past that date. There is also no incentive in the regulations for a pharmaceutical manufacturer to look for ways to lengthen that date of expiration."

This is a blatant case of "absence of evidence vs. evidence of absence." The FDA checks drugs after one year and finds that they are OK. This does not mean that the agency tested them after five years and determined whether they were not OK. This is where the one-year warning comes from. It means almost nothing. We can conclude from the FDA's limited study that the real number could be one year or 1,000 years. There is no way to tell.

Except there is

- The Harvard Medical School reported that the military, sick and tired of regularly throwing away expensive drugs, conducted its own study, in which they found that 90% of 100+ drugs, both prescription and over-the-counter, were perfectly good to use even 15 years after the expiration date.

- Likewise, a 2012 study reported in JAMA Internal Medicine revealed:

"Eight long-expired medications with 15 different active ingredients were discovered in a retail pharmacy in their original, unopened containers. All had expired 28 to 40 years prior to analysis...Twelve of the 14 drug compounds tested (86%) were present in concentrations at least 90% of the labeled amounts, the generally recognized minimum acceptable potency. Three of these compounds were present at greater than 110% of the labeled content."

More specifically:

Among the drugs that were tested that maintained greater than 90% of the labeled amount were acetaminophen, codeine, hydrocodone, and barbiturates

Well, would you look at that! Vicodin (hydrocodone plus acetaminophen) pills that have been sitting in a bottle for decades are still perfectly good—yet the FDA wants you to return them after just one year, based on zero evidence that the drug is no longer usable.

Likewise, the shelf-life of Dilaudid (hydromorphone) is given as three years but is almost certainly longer, maybe by a lot.

In an extensive study, the drug giant Sandoz analyzed 122 drugs and found that 88% of them were safe to use more than 5.5 years after the expiration date. Some of these included:

- Morphine sulfate (solution): 89 months (> 7 years)

- Fentanyl citrate (solution): 84 months

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl): 76 months

- Naltrexone hydrochloride (solution): 77 months

- Ketamine: 64 months

Some Generalities

- Almost all solid (tablet or capsule) drugs are stable past their expiration dates.

- Solutions are less stable than solids but may still be OK if stored properly.

- This does not hold true for most antibiotics, especially tetracycline, which does go bad, even when inside a capsule. Don't use expired antibiotics. Bad idea.

- Storage conditions matter. The enemies of drugs are light, heat, oxygen, and moisture. If you keep them sealed, in the dark (maybe even cold), the opioids I showed above will be useable for many years.

- But keep in mind that the FDA tells you the opposite.

What to do?

In my opinion, you have to be absolutely out of your mind to return expired opioid pills because there's an excellent chance you won't get them back when you really need them. Here's one of countless examples:

Should you be unfortunate enough to walk (or run screaming) into the ER at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn with a kidney stone, you'll run into this mentality:

Relying on opioids as the primary analgesics for moderate to severe pain is inadequate, unsafe, and costly...I am just trying to come up with a feasible, practical solution or alternative to opioid analgesia in the emergency department... For now, it is an alternative, but who knows what may happen later on. Perhaps we will be able to eliminate opioids altogether, which would be fantastic.

- Sergey Motov, MD, Maimonides Medical Center

All of you can make up your minds, but I think I'll hang on to my stash of old Percocet. You never know when you might be served a "Motov Cocktail" should you be unfortunate enough to be in Brooklyn at the wrong time.

NOTE:

[1] PROP aka, Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, a group that had inordinate input into the disastrous (and scientifically bereft) CDC Prescribing "guidance" pretends to be an organization that cares about protecting people from opioid-induced harm. Many people myself included, think that 1) they're only interested for purposes of self-enrichment; 2) they suck.

This is a revised version of a 2022 article. The question of old prescription drugs is still commonly asked.