“For far too long, ingredient manufacturers and sponsors have exploited a loophole that has allowed new ingredients and chemicals, often with unknown safety data, to be introduced into the U.S. food supply without notification to the FDA or the public.”

Closing the loophole created by food “ingredients,” “Generally Recognized As Safe,” (GRAS) will be a win for the MAHA "warriors" and others when it comes to food supply, but for supplements, those same warriors are more conflicted. But before your feelings about the messenger influence your thinking, let’s first consider the message. And to do that, it is worth taking a moment to review our food supply’s regulatory history.

A Regulatory System Built on Crises

The critical thread in understanding GRAS substances begins with the definition of adulterated and its subsequent enforcement and oversight, as food “crisis” after “crisis” prompts Congressional action. Federal oversight of our food and drug supply was established with the 1906 Food and Drugs Act, which focused on prohibiting the marketing of foods or drugs that were “misbranded” or “adulterated.”

“We saw meat shoveled from filthy wooden floors, piled on tables rarely washed, pushed from room to room in rotten box carts…gathering dirt, splinters, floor filth and expectoration of tuberculous and other diseased workers”

- Labor Commissioner Charles Neill and Social Reformer James Reynolds

In the context of 1906, Congressional concern addressed intentionally added dangerous materials and food rendered unpalatable by improper processing, the adulterants,

"any added poisonous or other added deleterious ingredient which may render [the food] injurious to health … or in part of a filthy, decomposed, or putrid animal or vegetable substance…"

There was no required proof that an adulterant was injurious, and the law additionally prohibited "aesthetic adulteration," alterations that we now associate with marketing and palatability, such as food coloring and emulsifiers, irrespective of any health risk or benefit.

The FDA was given enforcement power to punish or interdict adulteration after the fact; its role in evaluating the safety of substances and processes before they were introduced came decades later. It took another tragedy to move the government to shift the burden of proving safety to manufacturers.

A Sulfanilamide Disaster Prompts Action

"The first time I ever had occasion to call in a doctor for [Joan] and she was given Elixir of Sulfanilamide. All that is left to us is the caring for her little grave. Even the memory of her is mixed with sorrow for we can see her little body tossing to and fro and hear that little voice screaming with pain and it seems as though it would drive me insane.”

– Letter to President Roosevelt

In the fall of 1937, children and adults treated for sore throats began suffering kidney failure, abdominal pain, and, in some instances, convulsions. Within two months, there were 100 deaths. The culprit, a reformulation of sulfanilamide, the first commercially available antibiotic, was used in streptococcal infections that had been found safe when prescribed as a tablet or powder. A demand for a liquid form prompted one firm to find that sulfanilamide dissolves in diethylene glycol, poisonous “anti-freeze.” (No longer used.) The company’s control lab found the new formulation’s raspberry flavor, red appearance, and fragrance acceptable, and it was shipped nationwide. While selling a lethal product was not the manufacturer's intent, it was the outcome.

The sulfanilamide preparation was removed under the older 1906 law as “misbranded,” [1]. Still, the incident prompted the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FD&C Act), which represented a further step in the evolution of US food safety regulation, broadening food safety provisions to include adulteration resulting from unsanitary processing.

From Cranberries to Chemicals

In the booming post–World War II era, America’s dinner tables filled with foods made brighter, sweeter, and longer-lasting by a growing list of chemical additives. Science promised convenience, but by the 1950s, doubts crept in. In 1952, responding to growing concerns, Congress established a select committee, chaired by Representative James Delaney, to investigate the increasing use of chemicals in food. Congress, as reactive then as it is today, required another crisis to act.

In 1959, traces of a weed killer, called aminotrazole, linked to cancer were found in holiday cranberries just weeks before Thanksgiving. Shoppers panicked, sales collapsed, and headlines blared warnings about what might be lurking in the nation’s food supply. Public trust wavered, and Congress responded to the Great Cranberry Scare, with Delaney’s committee's work forming the basis for crucial legislative changes.

How GRAS Came to Be

While much has been written about the Food Additives Amendment’s Delaney Clause,

"…no additive shall be deemed to be safe if it is found to induce cancer when ingested by man or animal."

The legislation’s most critical shift was dramatically strengthening federal oversight by introducing premarket approval for new food ingredients and “food-contact” chemicals (packaging materials) to be evaluated solely on safety, with any beneficial value unweighted in the analysis. The FDA and Congress, acknowledging limited resources, required industry to bear the burden of conducting studies to support approval, echoing today’s requirement for pharmaceutical companies to bear the burden for the studies of the product's safety and efficacy.

Yet in creating these stronger safeguards, Congress also carved out exceptions—chief among them, the category of ingredients ‘Generally Recognized As Safe.’ It was the government’s fiscal limitations and the impracticality of reviewing thousands of already-used substances that enabled GRAS regulation. To allow a focus on genuinely new or potentially risky additives, an exception to formal FDA review was made for ingredients and substances with a history of safe use, or “generally recognized by qualified experts" as safe, the GRAS exception. [2]

In 1969, the FDA removed cyclamate salts, an artificial sweetner, from its GRAS exemptions because of safety questions, prompting President Nixon to direct the FDA to reexamine the safety of GRAS substances. The FDA initiated both a review of selected GRAS substances and its approval process. In 1997, to again eliminate resource-intensive procedures, the FDA replaced GRAS “affirmation” with today’s GRAS “notification." That exception, intended for harmless and familiar ingredients, has evolved into four distinct approval pathways.

Four Pathways to ‘Safe’

Today, GRAS determinations follow one of four routes—each with different implications for oversight and public trust. Perhaps the most acceptable is the “common use in food pathway,” where some ingredients, safely consumed for generations, provide a "real-world" safety record. Examples include salt, Vitamin C, baking soda, various spices and herbs, and certain enzymes and plant extracts found in “cultural and traditional” uses.

A more “scientific” approach, utilizing studies and meta-analysis, takes one of three paths.

- FDA-Initiated GRAS Determination: The FDA conducts a scientific review. Often, reviewing existing substances already in use, responding to new scientific information, as was the case with the banning of cyclamates and trans fats. This is a potential path in addressing public health concerns prompted by MAHA and the regulatory required public comment periods.

- GRAS Self-Determination: Manufacturers undertake the process to determine that a substance is GRAS for its intended use. This self-determination pathway appears rigorous: necessitating a qualified expert panel, comprehensive safety assessment, and documentation of the entire evaluation process. However, manufacturers are under no legal obligation to notify the FDA of substances they have determined as GRAS, nor are they prohibited from using them. [3]

- GRAS Notification Program: a middle ground between the two, involves voluntary notification of the manufacturer’s self-determination. The FDA then issues a response, determining whether there are “no questions” regarding safety, raising questions, or declining to evaluate the notice at all. This pathway provides regulatory oversight, a public record of agency review, and a stronger defense in court by demonstrating reliance on federal oversight. However, this approval offers no immunity if the product later proves harmful or if key safety data was withheld.

Under US law (21 U.S.C. § 321(s)), “generally recognized” means that the safety of the substance is widely known and accepted by qualified experts based on publicly available information (e.g., published studies, historical food use). It’s a regulatory, not scientific, standard, focused on whether there is enough credible, public evidence to support safe use; it makes little distinction whether the science is cutting-edge or unanimous. These pathways vary in rigor, but the most controversial is self-determination, which critics say leaves the public and the government in the dark

Industry Influence and the 99% Claim

“Since 2000, the food and chemical industry has greenlighted nearly 99% of food chemicals introduced onto the market without federal safety review… The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for ensuring food is safe. But the industry instead is deciding what food chemicals are suitable for people to eat.”

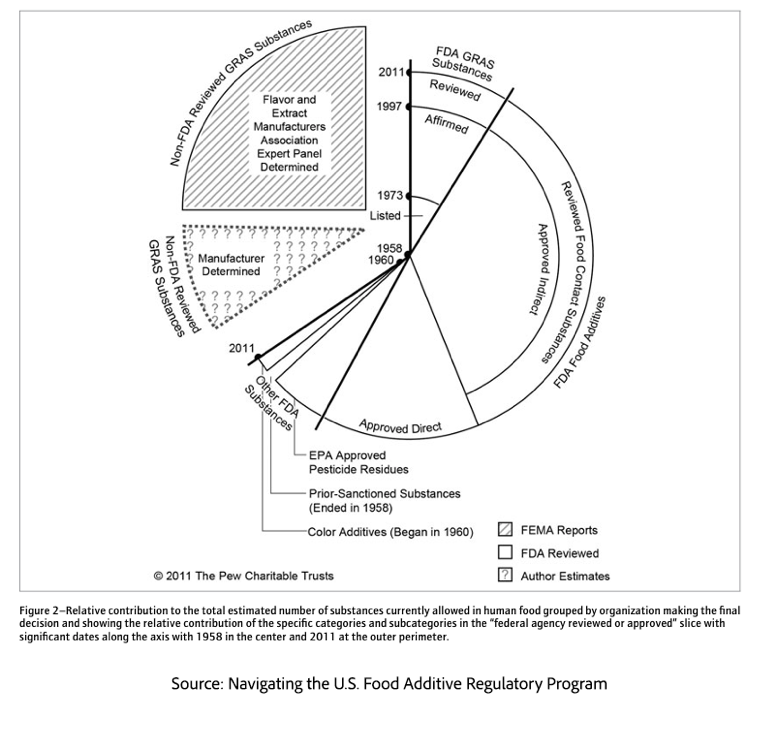

Certainly, this quote raises concerns, and it is tempting to believe that industry, not the FDA, is deciding what food chemicals are suitable for people to eat.” Fortunately, it is not quite true. The “99%” is an estimate, coming from a 2011 study that drew “upon food safety experts to make informed estimates.”

Certainly, this quote raises concerns, and it is tempting to believe that industry, not the FDA, is deciding what food chemicals are suitable for people to eat.” Fortunately, it is not quite true. The “99%” is an estimate, coming from a 2011 study that drew “upon food safety experts to make informed estimates.”

No one knows how many GRAS substances are self-determined; they are not reported.

The data on GRAS ingredients that have been reviewed by the FDA can be found here. There are now 1234 chemicals on the list. Roughly 1% are pending, the manufacturer voluntarily withdrew 18%, and 1% had inadequate information to make an FDA determination. Of the remaining 80%, the FDA has reviewed the industry-supplied data and given a “no questions” notification. The source of the data, from industry rather than outside experts, makes it, in the eyes of EWG, suspect. The imbalance is not solely the result of corporate overreach; the structure of the approval system creates strong incentives to avoid the formal FDA pathway.

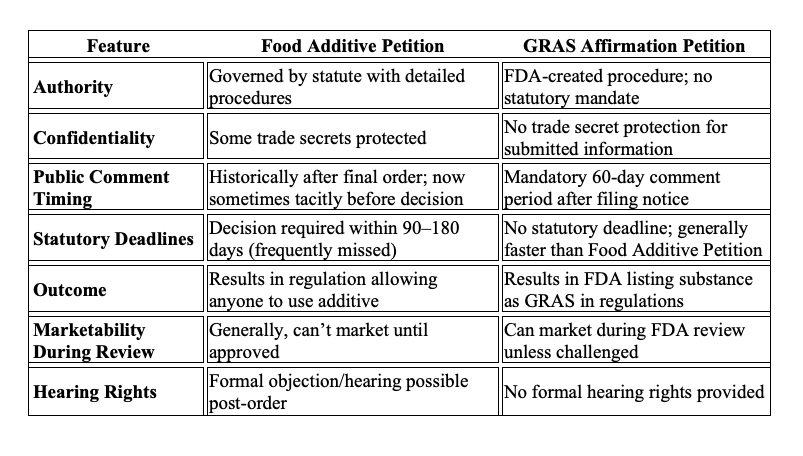

Both FDA-researched food additive petitions and industry-researched GRAS affirmation provide a degree of liability coverage, require detailed manufacturing, safety, and functionality data, and involve public comment. However, the differences, particularly with marketing and time to determination, significantly favor affirmation.

Despite the additional costs in time and the inability to market during a long interval, the FDA's food additive pathways result in a non-exclusive regulation “authorizing the use of the additive by any person wishing to do so.” Why bother?

Challenges To Reform

GRAS status is not permanent, as demonstrated by the removal of cyclamates and trans fats from the list. Approval can be withdrawn after an investigation prompted by changes in usage, adverse event reports, or scientific advances in toxicologic analytics or disease epidemiology. As the GAO reported in 2010,

“FDA’s oversight process does not help ensure the safety of all new GRAS determinations.”

Secretary Kennedy’s concern over the GRAS loophole is warranted.

There are two noteworthy challenges to Secretary Kennedy’s quest to eliminate the GRAS loophole.

Former FDA Commissioner Dr. David Kessler is urging the agency to revoke the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) status for refined flours, high-fructose corn syrup, and a range of emulsifiers and stabilizers commonly used in ultra-processed foods. Similar to his approach to tobacco regulation, he suggests flipping the script, requiring companies to prove the safety of their products before marketing them. Surely, this approach will find some MAHA "warriors" in agreement despite the fact that it is impossible to prove, with complete certainty, safety.

More covertly, GRAS Self-Determination has been used by supplement manufacturers to bypass the more rigorous FDA review of new ingredients in supplements, where there is no self-determination – manufacturers must submit data for FDA review. However, if an ingredient is first introduced as a food product, it can be GRAS self-determined, and then that ingredient, now GRAS-approved, can be freely added to a supplement without further review.

“In one case, the makers of Prevagen tried and failed twice to get FDA approval for its key ingredient, apoaequorin. After slipping it into a drink and self-certifying it, they withdrew their notice when the FDA raised concerns — yet the product is still on shelves today.” – NY Times

As the NY Times continues,

“In the run-up to the 2024 election, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. vowed to end what he called the government’s “aggressive suppression” of vitamins and dietary supplements. It’s a stance shared by several in his inner circle, many of whom have deep ties to the supplement industry. …Kennedy’s challenge is a tricky one: railing against predatory practices in mainstream food and medicine while also pushing to loosen federal oversight of alternative health products.”

Closing the GRAS loophole of self-determination will foster trust and transparency, potentially making our food supply safer. Will Secretary Kennedy apply this treatment to ultra-processed foods alone, or will he include supplements? That may tell us all we need to know about whether the goal is to Make America Healthy Again or to continue to line the pockets of some of his closest supporters.

[1] It had been sold as an elixir, which, by definition, is alcohol-based.

[2] A second exemption was granted to "Prior Sanctioned" substances, which were previously exempt from premarket approval by the FDA or USDA.

[3] This “safe harbor” against liability is lost if new information suggests safety concerns, and the FDA shows that the substance may be “injurious to health.”

Sources: FOOD SAFETY REGULATION: Reforming the Delaney Clause Annual Review of Public Health DOI: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.313

Sulfanilamide Disaster FDA Consumer Magazine

GRAS Status: Ensuring the Safety of Food Additives Food Safety Institute

FDA's Approach to the GRAS Provision: A History of Processes Archived

Navigating the US Food Additive Regulatory Program Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety DOI: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00166.x