“We think wearables are a key to the MAHA agenda. …It’s a way people can take control of their own health. They can take responsibility. They can see, as you know, what food is doing to their glucose levels, their heart rates and a number of other metrics as they eat it, and they can begin to make good judgments about their diet, about their physical activity, about the way that they live their lives.”

- HHS Secretary Kennedy

Wearables are smartwatches, bracelets, rings, and patches with built-in sensors that track a variety of health metrics, such as heart rate and rhythm, exercise and sleep patterns, and physiologic data, specifically blood glucose levels. To understand their impact, we need to know about their efficacy and safety. Let’s consider the two most popular wearable offerings, blood glucose and rhythm detection.

Blood Glucose Monitoring – Data or Doomscrolling?

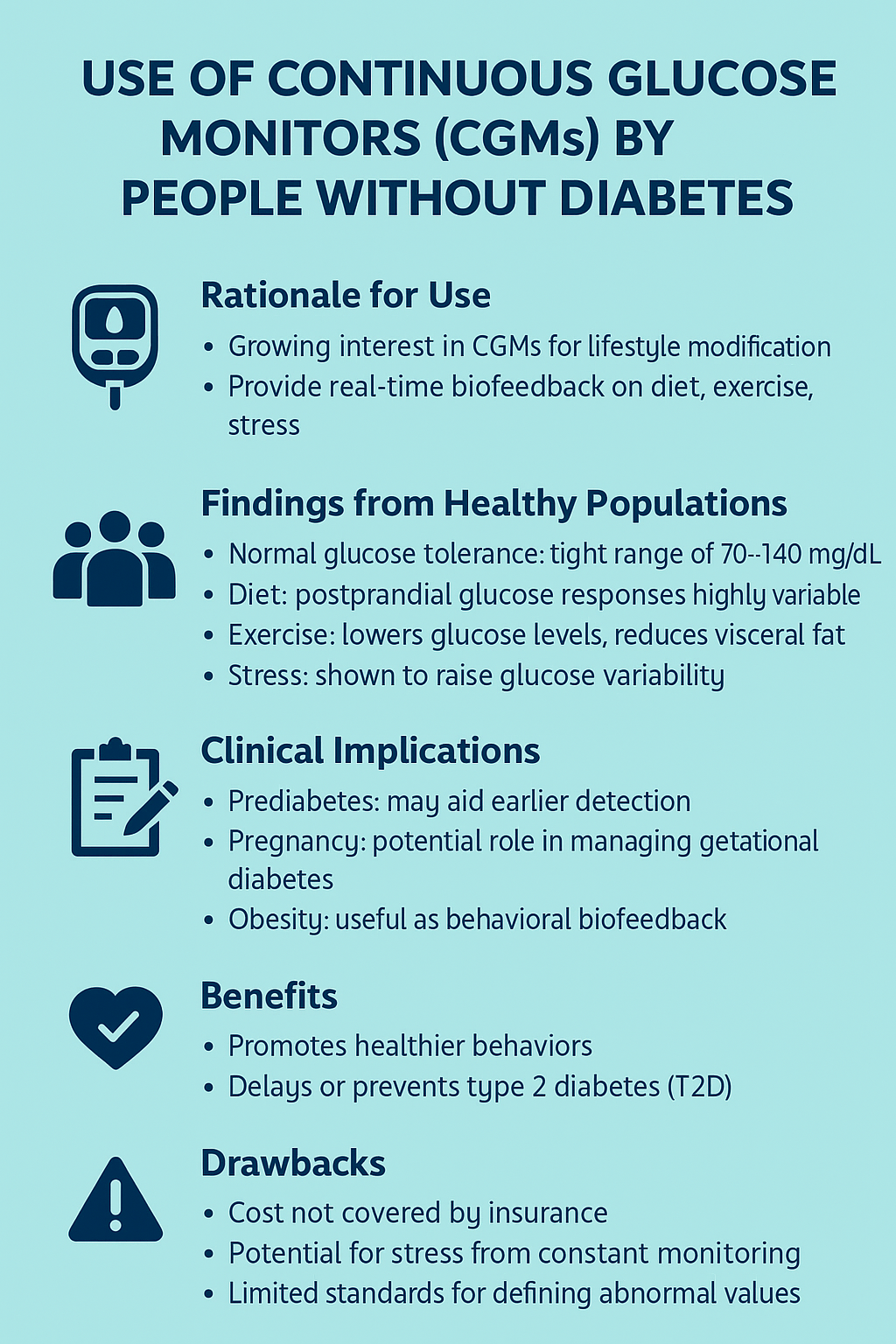

In 2022, the FDA granted “breakthrough device designation” to a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) for use by individuals without diabetes. The idea was simple: track your blood sugar in real time so you can see how meals, exercise, and daily stress affect your body. For enthusiasts of the “quantified self,” this promised instant feedback.

However, upon examining the studies, the picture becomes murkier. A meta-analysis found that most healthy individuals maintain a reasonable glucose range (70–140 mg/dL). Still, responses to the same meal varied wildly, depending on nutrients, time of day, and even stress levels. Exercise generally lowered glucose levels, but the variability was so broad that “normal” became difficult to define. In other words, your numbers may reveal more about context than the disease itself.

The researchers identified several potential uses, including the detection of “prediabetes” and gestational diabetes. CGMs also have a potential role in lifestyle modification, specifically in improving weight loss, dietary adherence, and physical activity, serving as a feedback loop to encourage healthy behavior. While pilot studies have shown high satisfaction, usability, and, most critically, motivation in their use, whether this extends to less interested “quantified-self” individuals will be a critical factor in the wearable’s impact.

There is virtually no risk associated with using a CGM device, other than the cost. Other than tape allergies or rare skin trauma, there are no physical downsides. There is a potential for “stress” from the constant monitoring, but like CGMs’ benefits in the walking well, there is scant research.

However, there are two significant limitations to the use of CGMs by individuals without diabetes, which should give us pause: the absence of a consensus on what defines “abnormal” and how to respond. Analysis of day-long CGM data showed that many self-reported healthy participants exhibited postprandial glucose dysregulation. In one study, 15% of “healthy” adults and over a third of those with prediabetes spiked above 200 mg/dL after meals. Is that a warning sign, or just unique physiology? The exact role of improving glycemic variability and the means to achieve such “improvement” remain open questions.

A recent study examining expert clinical interpretation of “atypical” CGM reports in individuals without diabetes found significant variability among clinicians with extensive CGM experience. The modest agreement was that more than half of clinicians recommended follow-up with a healthcare provider if CGM data showed more than 2% of time above 180 mg/dL. This finding is particularly relevant given that in the Framingham Heart Study, about 20% of adults spent more than 2% of time above this threshold. CGMs marketed to people without diabetes will place added time burdens on healthcare providers, additional screening costs to society, while leaving patients with unclear guidance and no apparent reduction in risk. The current evidence does not support CGMs as a stand-alone screening tool. Further research is needed to clarify benefits, best practices, and standards.

If glucose monitoring raises more questions than answers, heart rhythm tracking brings its own brand of uncertainty—this time from your wrist.”

Heart Rhythms – My Watch Raises Concerns

For this, we turn to the Apple Watch, the first of the wearables to receive FDA approval for passive detection of atrial fibrillation, a common disorder of the beating of the heart. In a fib, it's more common term, the heart’s upper chambers beat so fast they stop pumping effectively. Blood pools, clots form, and when normal rhythm resumes, those clots can head straight to the lungs or brain—causing pulmonary hypertension or stroke.

The study of interest, the Apple Heart Study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that

- Wearable devices can flag atrial fibrillation, especially in older adults, offering early detection of silent arrhythmias tied to stroke risk. Of the 419,000 participants enrolled, about 2200 participants were flagged by the watch [1]

- Approximately 945 individuals, or roughly 42%, followed up with a physician, and of those, 658 underwent further testing.

- Of those undergoing further testing, about two-thirds, or 450, completed more formal monitoring.

- Of that 450, 153 had atrial fibrillation confirmed, according to what the study reported as 34%.

Of course, if one were to change the denominator to reflect those flagged and seeking confirmation, that percentage drops to 16%. If we consider all those notified, only about 18% had a clinical diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. As a screening test, the Apple Watch generates a large number of false positives. Put another way: four out of five alerts were false alarms.

For the 18% who actually had A-fib, early detection could be life-changing. But for the other 82%, the watch delivered anxiety, unnecessary follow-ups, and a flood of new appointments with little medical payoff. A parallel study of Fitbit users, involving 450,000 people, found an even lower confirmation rate—about 7% of those notified were ultimately diagnosed.

When your watch cries wolf four times out of five, the question becomes: who benefits? With mixed evidence and rising anxiety, how do regulators draw the line between a helpful gadget and a medical device?

Regulatory Oversight or a Nod and a Wink?

With so much hype and so many gray areas, the obvious question is: where are the regulators? The FDA’s answer has been to tuck most wearables under its “General Wellness: Policy for Low Risk Devices,” distinguishing between diagnostic devices and general wellness products.

If a device is marketed solely to encourage healthy behaviors (such as diet tracking, fitness, or performance optimization) and is low-risk, meaning it is non-invasive, not implanted, and unlikely to cause harm, then it may fall into the wellness category and avoid active FDA regulation.

Within this policy, wellness devices can promote a general state of health without referencing a specific disease, e.g., fitness, stress management, or can be linked to lifestyle choices that lead to well-established risk reduction, e.g., weight control in diabetes.

The Apple Watch, which uses optical sensors to detect irregular heart rhythms, falls under the wellness policy rather than being regulated as a medical device or diagnostic tool. Initially, CGMs complicated this picture because most current models are minimally invasive, with microneedles inserted into the skin, requiring FDA review before they can be marketed, even if framed as wellness tools.

But in March 2024, “to support innovation that addresses health equity by moving care and wellness into the home setting,” the FDA approved a CGM device for individuals without diabetes, “who want to better understand how diet and exercise may impact blood sugar levels.”

The FDA’s wellness device policy also extends to software functions that analyze data generated by these devices. Software intended only to “maintain or encourage a healthy lifestyle” and not directly tied to diagnosis, cure, or treatment is excluded from FDA oversight. This means that an app that interprets CGM data to show trends for “optimizing nutrition” or “supporting athletic performance” does not need FDA clearance if it stays within the wellness framing. Similarly, third-party apps that analyze Apple Watch heart rate data to suggest stress reduction techniques or fitness improvements can bypass regulation.

The practical effect is that hardware is regulated when it is invasive or explicitly diagnostic, but software layered on top of approved devices can avoid FDA review if it adheres to wellness claims. While creating flexibility for innovation, it also opens the door to variability in quality and marketing, as some apps may blur the line between wellness and medicine. This hands-off approach conveniently aligns with the business models of officials now championing wearables under MAHA, forsaking the concerns of many of the MAHA moms.

Add in the political theater. Secretary Kennedy, embracing wearables as central to the MAHA agenda, is flanked by the Means siblings: one who advocates for medical savings accounts for alternative medicine and lifestyle devices, and the other, our Surgeon General nominee, who has a CGM lifestyle company, which raises questions about potential conflicts of interest. Or is this just a new version of Generally Recognized as Safe?

“The feature is not intended to replace traditional methods of diagnosis or treatment.”

That sounds an awful lot like a supplement’s regulatory disclaiming loophole, “This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

Wearables may glitter with the promise of empowerment, but scratch the surface and the data are messy, the guidance inconsistent, and the benefits—at least for the walking well—more aspirational than actual. Yet Silicon Valley continues to sell graphs as gospel, and Washington appears content to go along. In the end, these shiny gadgets may prove less a revolution in health than a subscription service for worry, providing innovation through marketing, medicine via notifications, and wellness via algorithms.

[1] The study population skews younger, with a lower incidence of a fib, making its value for screening more problematic, and its generalizability limited.

Sources: Use of Continuous Glucose Monitors by People Without Diabetes: An Idea Whose Time Has Come? Journal of diabetes Science Technology DOI: 10.1177/19322968221110830

Expert Clinical Interpretation of Continuous Glucose Monitor Reports From Individuals Without Diabetes Journal Diabetes Science Technology DOI: 10.1177/19322968251315171

Large-Scale Assessment Of A Smartwatch To Identify Atrial Fibrillation NEJM DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901183